FORMA

Vol. 1, No. 1 (2019)

In the inaugural issue of FORMA, we feature essays that question predominant political sensibilities in Latin America and foreground disagreement with primary models for analyzing cultural production from the region. Among the concepts and models featured in these critiques are Aníbal Quijano's coloniality of power, Jacques Rancière’s politics of the part who have no part, slow cinema, and the promise of AMLISMO in Mexico.

State Fetishism: Neoliberal Democracy and Political Imagination in Mexico

But beyond the caudillo deliriously haunting his people on a daily basis, endangering democracy with messianism, what concerns me is that one of the regime’s stated goals is to dismantle the “mafia in power.” This means that the political imaginary promoted by the current regime is sustained by a fantasy of a government that aspires (in discourse, at least) to a capitalist state but without a capitalist class. How this could be feasible is not currently clear.

(De)Colonial Sources: The Coloniality of Power, Reoriginalization, and the Critique of Imperialism

Indeed, there may be no concept more pivotal and constitutive of decolonial thought than Aníbal Quijano’s coloniality of power. However, aside from the centrality ascribed to it and the countless assertions of the term and bibliographic citations of Quijano’s work, very little has been written on how exactly Quijano himself conceives and formulates the coloniality of power in his own writings.

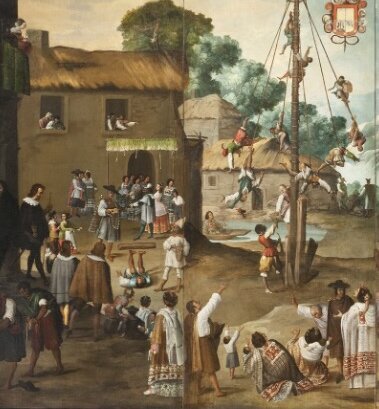

The Partition of the Pelado: Poverty, Art, and the Making of the PRI

If someone were really interested in creating a world free of poverty, why would they turn to an aesthetic tradition that historically has been used to police and normalize behavior and deny access to jobs, land, political power and other material resources? What good are novels, images and stories if they have little relation to the poor’s demands to have their health, housing and infrastructure needs seen and heard? In short, if someone is in need of a real, material solution to their situation of poverty, why fictionalize it?

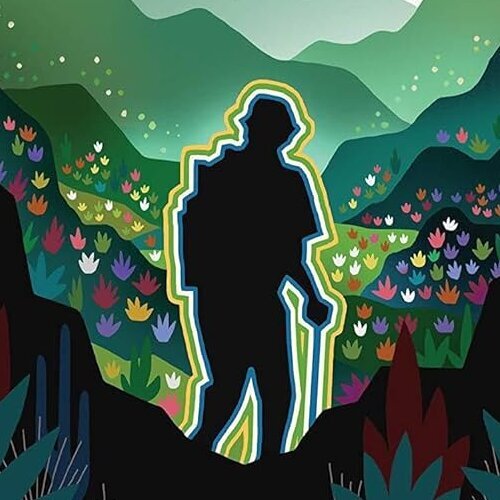

Toward an Aesthetics of Dead Time in Carlos Reygadas’s Japón

What I want to suggest is that the aesthetics of dead time in Japón, emblematically developed through the extensive long takes and pans, is an anti-theatrical attempt to assert the film’s status as a measured artistic construction. Japón seeks to overcome its theatricality by asserting that this time be understood as autonomous rather than as indivisible from the viewer and his or her experience. That is, Reygadas’s aesthetics wishes to create an “instantaneous mode of unity” that makes time meaningful in the movie. In sum, the narrative with a clear beginning, middle and end, along with the use of non-professional actors, montage, and especially the long takes and pans, all aim at creating a sense of time that will be understood within the limits of the frame.