The Prolific Roads of Reedification: Literature, Architecture, and Autonomy in Post-Revolutionary Mexico

“Art has always been free of life; its flag has never reflected the color of the flag flying over the city fortress.”

Victor Shklovsky, “Ullia, Ullia, Marsiane!”

“Banderas clamorosas / repetirán su arenga proletaria / frente a las ciudades.”

Manuel Maples Arce, Poemas interdictos

This essay reflects on how literature and architecture confronted the question of autonomy in post-revolutionary Mexico, that is, how literature and architecture modeled for themselves, in theory and practice, their own independence from society. 1 The post-revolutionary decades witnessed remarkable transformations linked to a variety of modern processes, which inevitably led Mexican artists and intellectuals to reflect on the social character of art and to pay particular attention to the increasing self-awareness with which artworks negotiated their ideological determinations. I suggest an approximation to this problem through the language of reedification, which maintained prevalence as a master trope during the post-revolutionary decades and articulated the symbolic, political, and material dimensions of the struggle to reconcile aesthetic and revolutionary incumbencies. The first part of the essay analyzes the question of the social function of literature through two sets of oppositions: first, between proletarian revolutionary aspirations and the Mexican state’s developmental pursuits; second, between the divergent aesthetic infrastructures of cosmopolitanism and cultural nationalism. I argue that although proletarian literature and vanguardism tend to be constructed as absolute contraries, they are nonetheless proximate in their rejection of political structuration and their adoption of unmaking as the ultimate vitalist gesture. This scantly prospected harmony, I further elaborate, became the basis for a particular distortion in post-revolutionary Mexican literature based on the association of aesthetic autonomy with the repudiation of state power rather than with the artwork’s internal cohesiveness and social functionlessness. The second part of the essay turns to architecture as a site where literature’s averseness toward social edification is disputed. Analyzing the ascendancy of functionalist architecture, I argue that functionalism’s assertion of aesthetic value briefly congrued with the struggle to give material form to the liberatory ideals of the Mexican Revolution. I further suggest that the momentary alignment between functionalism’s method and the historical demands of the post-revolutionary period required a radical commitment to structuration. I conclude the essay by arguing that capitalism’s arbitrary reappropriation of functionalism’s commitment to structuration, rather than a historical disclosure, realizes the possibility of repurposing autonomous structures, and therefore opens the door to imagine the kinds of repurposing that would enable radical alternatives to capitalist forms of sociality.

Narrowing Paths

First opposition. In the opening scene of José Mancisidor’s 1932 proletarian novel La ciudad roja (The Red City), a group of soldiers forces a family out of a shanty. A nameless “representative of the law” oversees the eviction and cynically responds to the aggrieved crowd that has come to gather around him: “The revolution—no doubt about it!—has left behind, through the development of its wise and sound process, its barren and misleading destructive period, to gallantly step into the prolific roads of reedification.” 2 Reflecting on the national situation the representative continues: “The moment is different: creative, edifying, optimistic! We must instill confidence in capital so that the Fatherland may prosper and grow.” 3 In a couple of pages, the elementary conflict between capital and labor is remodeled into an arrant opposition between the nation-building arithmetic of the Mexican state (construction, order, reedification, law) and the tidal waves of the proletarian revolution, the socialist call “to destroy the whole existing social order.” 4 Voiced by a state official, the metaphor of reedification tempers the clamor of the revolutionary insurrection, it outlines a historical continuum between destruction and reconstruction, anarchy and constitution, mass upheaval and democratic consensus. Against this bourgeois conception of the revolutionary war, 5 Mancisidor’s novel, as does proletarian literature more broadly, cultivates the conviction of the actuality of the revolution, its historical vitality as an oncoming event. 6

The opposition, mediated in Mancisidor’s novel through the representation of the 1922 tenant movement of Veracruz, 7 signals the emergence of two increasingly contradictory worldviews: the first one, stirred by the proclamation of a new beginning, projects the struggle for agrarian redistribution and national liberation into a linear map that modishly connects armed conflict to developmental pursuits; 8 the second one, oriented toward internationalism and world revolution, disputes the compromise with any form of class rule and thus, upholds the need for insurgent continuation and socialist finality. The ideological affirmation of the former over the latter throughout the 1920s and 1930s, cements the temporal boundaries between a revolutionary and a post-revolutionary moment in Mexican history. In the aftermath of Álvaro Obregón’s presidency, the contrariety between these perspectives continued to grow to the point of irreconcilability. But before such historical tipping point was reached, the ideological gap was continually dissolved under the pressures of mass mobilization, class restructuring, and world history, giving rise to a variety of converging forms in an effort to carve out a coherent sociohistorical trajectory for the country (e.g., in the militant aesthetic of Mexican muralism). This was the situational singularity in which the debate on literary and artistic autonomy was revitalized in Mexico.

Second opposition. The debates around cultural nationalism that took place in the 1920s and 30s laid the ground for the reconfiguration of the Mexican literary field in the post-revolutionary period. As has been well established, 9 the 1923 Congress of Artists and Writers, the 1924-5 controversy around effeminacy and virility in Mexican literature and, above all, the 1932 polemic between the proponents of nationalism and cosmopolitanism, configured a new cultural landscape for literary and artistic practice in the country. 10 While heavily infused with the rhetoric of nationalism and national authenticity, the exchange regarding literature’s conformity to the official promulgation of a Mexican identity—a genuine nationality in José Vasconcelos’ formula—oftentimes raised concerns that went beyond national criteria to reflect on the constitutive opposition between aesthetics and politics as such. Xavier Villaurrutia, for example, voiced his skepticism toward the politicization of art when he argued: “Should the literary youth interest itself in politics? Rather, I think that politics . . . should interest itself in the literary youth . . . Creating fellowships, helping realize works of general interest, establishing awards for poetry, novels, and theater would be, in Mexico, something as befitting for the Mexican spirit as building dams, opening roads, and drawing bridges.” 11 Villaurrutia’s suggested equivalence between literary and industrial passions conveys a peculiar approximation to the history of “the development of actual works of art as self-legislating artifacts,” 12 whose originality lies in the unambiguous recognition of the fluctuations imposed on such a process by the compulsions of dependency and underdevelopment. The interrogation of the conditions of (im)possibility of the autonomy of the work of art disclosed by the demands of Villaurrutia and his cohort, however, has remained partially concealed behind the binary redundancies that permeate both the primary texts and their critical appraisals, the result being a heightened but similarly oversimplified confrontation between what Guillermo Sheridan characterizes as the “subjects of the diffuse fatherland of modernity,” on the one hand, and the subjects of a set of “narrow national affirmations,” on the other, 13 one of the many avatars of the opposition between the proponents of art for art’s sake and the advocates artistic commitment. 14

Between these two sets of opposing worldviews a series of assumptions begins to take shape, where the installations of form are made to betray both the intellectual vitalism of literatura de vanguardia and the communist invective [arenga] of literatura proletaria. 15 Therefore, Lorenzo Turrent Rozas, one of the main proponents of proletarian literature in Mexico, can celebrate the Russian avant-garde for its ability to decompose bourgeois aesthetics 16 while denouncing the ideological disorientation of the so-called Novel of the Revolution and estridentismo, the former absorbed in the anecdotal, the latter corralled by its elitism. 17 Proletarian literature’s approximation to the problem of (re)edification becomes temporally dissonant, capitalism must be torn asunder now to allow for the construction of socialism hereafter. In the eyes of Turrent Rozas, the Novel of the Revolution is simultaneously constrictive and disperse; proletarian literature is meant to reengineer the former’s ideological opacity into a forthright path toward socialism—Ruta [Route] is the name of the magazine Turrent Rozas and Mancisidor found in 1933. 18 “Our literature,” concludes Turrent Rozas, “is almost unanimously bourgeois . . . in its lack of ideology and organization.” 19 This same charge will be advanced against the state-sponsored program of cultural nationalism, whose assay to substantiate a Mexican identity forestalls the projection of a socialist future. Tellingly, Turrent Rozas’ approximation poses the need to ideologically hold together the efferent impulse of dismantlement—the revolutionary call to pull down the walls of the bourgeois city-fortress—and the centripetal motion of formation—Gladkov’s Cement (1925) provides him with an opportunity to celebrate the first stage of the edification of socialism (the dictatorship of the proletariat) and the programmatic construction of a classless society. But in the historical conjuncture of the 1920s and early 1930s, in light of the Mexican state’s increasingly successful effort to contain intellectual life, 20 proletarian literature decants itself in favor of the centrifugal stirrings of unmaking: “To jump over the barricades. To be an overflowing torrent… To shatter… To ravage… To attack… To destroy.” 21 Here, the ideological query is resolved at the level of content:

The decision must be emphatic, categorical. Radical struggle that indicates a steady orientation for the masses, or conciliation with today’s oppressive systems, which will enervate us with momentary palliatives. The former will be an evident and edifying sacrifice; the latter, the exploited and suspicious attitude on whose wretchedness thrives the auspicious future of the traitors of the masses. The one will push us toward the future; the other will shackle us to the present. 22

Adorno’s commentary on Sartre’s literary theory seems befitting: “the work of art becomes an appeal to subjects, because it is itself nothing other than a declaration by a subject of his own choice or failure to choose.” 23 But while Mancisidor’s novel exhibits all the traits of an object that is thoroughly endowed with an external purpose, it remains symptomatic that the distinct gesture it elicits regarding the socio-symbolic procedure of formation turns out to be fully aligned with the overarching position of literary vanguardism: the rejection of synthesis.

Vanguardism, a term that is most porous in the context of the 1920s and 30s, often to the point of confusion, has been generally taken to exist in an oppositional relation to the institutionalizing impulses of the post-revolutionary state. Sheridan’s account of the divergent approximations to the question of the “national soul” during the 1932 polemic is revealing: “one could add that the expression to form the national soul also presupposes a decision that is pedagogical in nature, collective, epic, and institutional; whereas to search for it responds to an impulse that is speculative, individualist, domestic, and private.” 24 Thus Sheridan suggests a confrontation between a formative and a speculative approximation to the national question that is structured around the opposing faculties of composition and unmaking; while the nationalist camp instantiates the desire for literature to join the ranks of muralism and music in giving form to a Mexican nationality, the cosmopolitanism of Alfonso Reyes and Contemporáneos offers a speculative reprisal to the ideological trapping pits of “formative messianism.” 25 Jorge Cuesta, for instance, decries nationalism’s “narrowness of sight” and its tendency toward the “exaltation of the particular.” 26 He similarly celebrates art’s indifference toward content and rejects any attempt to popularize—i.e. subjugate to moral, political, or religious mandates—art’s autonomous universality. 27 Villaurrutia similarly takes pride in being part of a movement that has remained completely unattached, “free from all contamination, from all corruption.” 28 The violation of the tenet of “the immanent purposiveness of the work” 29 via its subordination to an external (political) purpose is, for Villaurrutia, Cuesta, and their cosmopolitanist brethren, the cardinal sin of cultural nationalism. Despite the free associations, sexist undertones, and ephemeral coalitions that modulated the polemic, the representatives of vanguardism were brought together by their critique of traditionalist inclinations and by a unanimous disavowal of literary edifications—a preference for the individual over the collective most clearly expressed by the characterization of Contemporáneos as a “group without group.”

At this point, counterintuitively and from opposite directions, the aesthetic tenets of proletarianism and vanguardism begin to closely align, as they both operate in diametric contradiction to the exacting procedures of state formation. While the means to circumvent these designations vary in each case, the problem confronting both remains one and the same: how to overcome the constraints produced by the political necessities of the national-popular state. Proletarianism works to demolish these strictures at the level of content—from the pages of Ruta Mancisdor mounts an attack on those writers who remain absorbed by questions of form but ultimately fail to express a revolutionary orientation at the level of content 30 —whereas vanguardism resists its incorporation into the grammar of nationalism by enveloping itself in the affectations of aestheticism. In both cases, however, the constructivist instantiations of mexicanidad become anathema to art’s displacing expositions. Unburdened by the universalist aspirations of vanguardism and the socialist realist overtures of proletarian literature, cultural nationalism will be at once censured for its institutional intimacies with the national-popular state and its disloyalties to working class struggles; for its ideological orientations—its overly political commitments—and opacities—its numerous political shortcomings. In both instances, the constrictive attributes of nationalism are made analogous to the ordering principles of structuration (patterning, edification, construction). 31 The affinity between literary modalities that are commonly understood to be absolute opposites allows us to reimagine the relation between proletarianism, nationalism, and vanguardism as a trigonometric identity, where each element can be expressed in terms of the other two, rather than as a relation of irreconcilable asymmetry.

A more common interpretation of the problem is recounted by Sheridan when he distributes these perspectives under the labels of “Marxists, nationalists, and vanguardists” and evinces their crosspollination, if only to emphasize how their ideological malleability favored political opportunism. 32 But the categorization itself remains relevant as it has been loosely transposed in literary critical discourse into an axiological scale corresponding to the practices of tendentious, committed, and autonomous art. 33 This approximation discards the historical critique that we have been sketching by forcing the problem of autonomy into a linear solution, in which the work of art is understood to exist within a “purification process,” “a volatilization of content, a moving of the represented material away from its worldly reference.” 34 With the benefit of hindsight, the consolidation of the national-popular state appears as the main obstacle to the continuation of this process, most notably after the revolutionary and nationalist imaginaries of the Mexican left begin to coalesce around the newly formed Party of the Mexican Revolution (PRM). Following the Popular Front strategy, the Mexican Communist Party—legally reinstated in 1935—aligns itself with the Mexican state’s project of national capitalist development, contributing, at least partially, to sequester the worker’s movement by assimilating it into the corporatist structure of the PRM. 35 But beyond the game of political and ideological alliances that shaped the Mexican 1930s, what interests us here is the way in which the gradual subordination of collective and class-specific interests to the developmentalist project of the Mexican state—a process that was set in motion by Obregón, deepened by Calles, and completed by Cárdenas—provided the historical breeding ground for the cultural debates of the 1920s and 1930s. The resulting configuration entailed a gripping displacement, where the state itself (regardless of its bourgeois, reformist, socialist, nationalist, or developmentalist lineaments), rather than the market (or a perhaps better term, capital) came to preside over the work of art’s entanglements with social life and mediate the analytical appraisal of its aesthetic and extra-aesthetic qualities.

The resulting dynamic becomes significant as it seems to synonymize artistic autonomy with political neutrality rather than with any form of internal cohesiveness, a position that more often than not leads to its analytical separation from the material development of productive forces, since it reduces the existence of the work of art to its remonstrance toward political power. To pose the problem in slightly different terms, at stake throughout the Mexican 1930s is the emergence of a new artistic matrix that accompanies the historical passage from the moment of ideological undecidability opened by the revolutionary conjuncture to a moment of national affirmation that is dependent on the premise of a fully developed capitalist sociality. Here, however, the term national immediately evokes Aijaz Ahmad’s question: “whose nationalism is it?” 36 Ahmad’s commentary on Third World Theory offers a relevant approximation to our problem:

[The] lack of an articulated central doctrine and the generality of anti-colonial stance in the post-colonial period gave the so-called [Third World] Theory the character of an open-ended ideological interpellation which individual intellectuals were always free to interpret in any way they wished, which in turn made the Theory particularly attractive to those intellectuals who did not wish to identify themselves with determinate projects of social transformation and determinate communities of political praxis, retaining their individual autonomies yet maintaining a certain attachment to a global radicalism. 37

The ideological opacity of the Mexican state made it similarly possible to configure nationalism in an open-ended way, turning it into a highly adaptable cultural form. Against this configuration, aesthetic autonomy could be upheld as a healthy counterweight to nationalist dogmatism, but not, in any case, as a viable resolution to the class conflict from which such dogmatism was being nurtured. Therefore, perhaps negatively, the aforementioned debates might indeed offer a unique, peripheral perspective on what Sarah Brouillette and Joshua Clover refer to as “the social conditions that make particular practices register importantly as ‘art’ and that make the ideal of autonomy a relevant criterion for assessing art’s quality or significance.” 38 Only when read against the backdrop of the emergence of a fully developed capitalist sociality do the nationalist mannerisms of the post-revolutionary state become legible, and the modernist and social-realist contestations to its formative injunctions completely historicized. Otherwise, we run the risk of falling into an essentialist trap, where the critique of national essentialisms ends up producing an essentialization of its own: the political valorization of deconstruction (taken here in its literal sense) as elementally antagonistic to the composed materialities of structuration, formation, and edification; in short, the essentialization of unmaking as the ultimate vitalist gesture. 39

I argue that in post-revolutionary Mexico, the metaphor of reedification offers a peculiar contestation to such essentialization of unmaking, for it communicates, at some very basic level, the mundane necessity of imagining structures for holding things together. And as Caroline Levine has argued, “Things take forms, and forms organize things.” 40 Perhaps with obvious translucency—since no other art is as immanently purposeful—the historical conjuncture of the Mexican 1930s finds in architecture a practical model to dispute the literary averseness toward social edification, i.e. to conceive of structuration as a social necessity rather than as an administered limitation.

Congruent Forms

Hannes Meyer, Swiss architect, second director of the Bauhaus, and former advisor to the Soviet Union on urban planning and development, visited Mexico for the first time in 1938 at the behest of Vicente Lombardo Toledano. One year later, Meyer returned to the country with the explicit purpose of spearheading the creation of the Instituto de Planificación y Urbanismo, a short-lived institutional experiment that embraced the functionalist and universalist ideals of modern architecture. His presence responded to the Mexican state’s interest in developing an overall urban strategy that, through a series of workers’ housing projects, would materialize the revolutionary promise of social equality and wealth redistribution. Meyer’s well-known commitment to functionalism aroused the imagination of Mexico’s professional elites. However, as Georg Leidenberger notes, when Meyer finally returned to Mexico he was no longer strictly invested in the premises of functionalism, but instead, in accordance with the aesthetic program of Soviet socialist realism, he had come to favor the architectural tenets of regionalism, a position that strongly disagreed with the modern impetuses of Mexican architecture. 41 The opposed views gave way to a bitter argument that ultimately led to Meyer’s fall into disrepute; none of his projects came to be developed and less than two years into his tenure as director of the Instituto de Planificación y Urbanismo the institution was shut down. Juan O’Gorman, Diego Rivera, and Mario Pani, all key figures in the nation-building venture of the national-popular state, distanced themselves from Meyer and rejected the bulk of his ideas about planning and the use of aesthetic and popular elements in architecture. The anecdote, if shallow, suffices to give a sense of how functionalism had come to dominate Mexico’s architectural scene by the end of the 1930s. The tenor of this agreement was set during the 1933 pláticas [conversations] convened by the Sociedad de Arquitectos Mexicanos, where many a luminary of Mexican architecture gathered to discuss the state of the profession. While many topics were debated during the pláticas, a central concern for all participants was the question of whether aestheticism and expressivity were compatible with the methods of functionalism and rationalism. 42

The architectural landscape of the 1920s had been dominated by the neocolonialist school that arose as a nationalist rebuttal to foreign—mostly French—influence during the Porfiriato. Although the 1920s saw a widespread use of new materials and construction techniques, 43 it was not until the 1930s that functionalism began to displace neocolonialist and other traditionalist forms of architecture, thanks in part to the official sponsorship of the state. The shift entailed a gradual dismissal of ornamentation and local attributes in favor of simplicity and austerity. The aspiration, as Leidenberger notes, was to arrive at a “prototypical form.” For the proponents of functionalism, “there was no room for artistic inclinations, which, at best, should be relegated to the sphere of the private and the intimate, bereft of any public relevance.” 44 The functionalist devotion to efficiency not only canceled out all established concerns about expressivity in architecture—a transgression for many of the attendants to the pláticas—but more importantly, it became the formal cornerstone of functionalism’s commitment to the social ideals of the Mexican Revolution. As Tavid Mulder argues, “[b]ecause of its ‘maximum efficiency,’ functionalism promised to modernize Mexico and fulfill the Revolution’s commitment to addressing social needs for housing and education. It constituted, in other words, an attempt to extend the revolution into architecture.” 45 Rationalist architecture was form repurposed into revolutionary function. The idea, as we will see, involves a meaningful reversal to the problem of autonomy as encountered in the 1932 polemic on literature and nationalism.

In his intervention during the pláticas, Juan O’Gorman, “the first significant interpreter of functionalism in Mexico,” 46 succinctly articulated the stakes of the debate when he asked whether it was “spiritual needs” or “material necessities” that should be the guiding principle of architectural composition. 47 In O’Gorman’s opinion, to privilege the former over the latter meant giving a wrongheaded preference to “subjective values” over “fundamental,” material ones (54). In his comments, O’Gorman criticized the formalist subterfuges of art for art’s sake and launched into a diatribe against the “artistic demagoguery” that characterized the proponents of “the existence of something divine, something that arouses a particular taste, a taste that pulls one closer to absolute beauty, a mystical taste that is elevating” (57). 48 For O’Gorman, these subterfuges led to one of two possible outcomes: the decay of architecture into a self-complacent game of light and shadow—a vacuous exercise determined by individual preferences—or the vapid recourse to tradition and archeological inspiration. In an effusive indictment of the former, O’Gorman asserted:

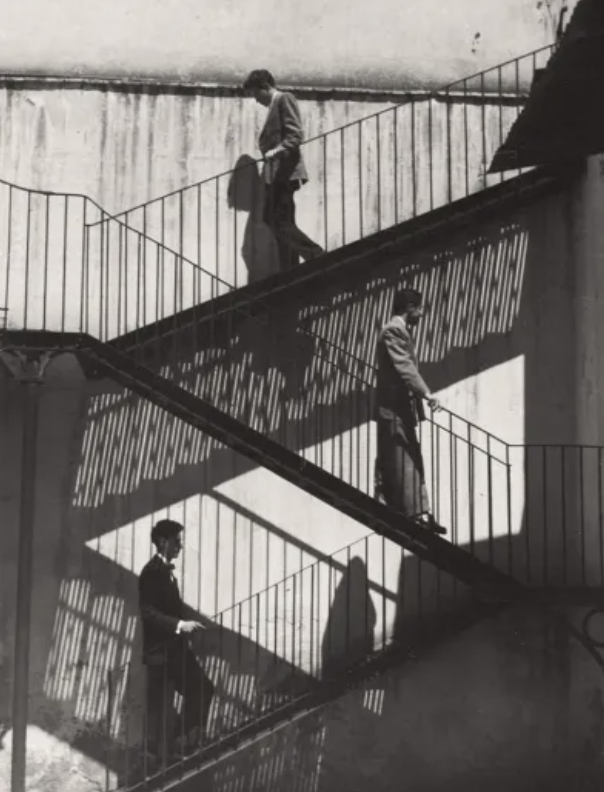

In art exhibitions you find the only interesting painting, which is the patent of thoughtlessness and falsity that is disguised using a very good excuse: superlative art, free art, art that is, let us say it, plainly anarchist, devoid of any kind of foundation, just the same (I regret to say it), as the picture presented to us by the houses of the new neighborhoods, the anarchist caricature of the Hipódromo, without order, without science, and without historical concerns of any kind, but in possession of one very good excuse: we are artists and we feel. (58) 49

Against the notion that the work of art presents us with something that evades rational explanation, i.e. something that can only be accessed affectively, O’Gorman raised the question: “who are those who feel?” (58). The answer had already been rehearsed by Jorge Cuesta during the 1932 polemic: “Only the artist recognizes the artist; only the best recognizes the best. Therefore art, true art, is, following Nietzsche’s expression, art for artists. The audience will never enjoy it.” 50 This kind of “artistic fanaticism,” as O’Gorman referred to it, was the architectural dead-end to which functionalism would provide a radical alternative. However critical, O’Gorman’s charge against the prevailing styles in architecture was not necessarily a charge against what we might call the politics of form—as, for instance, in Mancisidor’s adamant rejection of formalism—but a critique of those architectural products that, in his view, fulfilled superfluous and/or obsolete needs, forms that were the product of mere subjectivism or, in the case of neocolonialist architecture, a misappropriation (59). Both styles ultimately failed to provide a form adequate to the context of accelerated urbanization and industrialization that characterized post-revolutionary Mexico. O’Gorman’s critique, we should note, turned the question of architectural form into a problem congruent with that of social and scientific development: “You could think from what I’ve said so far that I disavow undisputed human and historical values, that I negate the aesthetic as one of the manifestations of human intelligence, but the confusion lies in considering the aesthetic as the means and end of the work, rather than its consequence” (59, my emphasis). 51 O’Gorman’s radical functionalism asserted aesthetic value as an unintended consequence of the work’s immanent horizon of rationalization, an involuntary product of material changes within a system of continuing renovation where necessity gave way to superfluousness in a cyclical manner.

In his critical appraisal of functionalism, Adorno similarly considered the new objectivity advanced by functionalism’s commitment to formalization as the result of an “emphasis on concrete competence as opposed to an aesthetics removed and isolated from material questions.” 52 Adorno’s formulation of autonomy offers some further insight into O’Gorman’s ideas: “the question of Functionalism,” wrote Adorno, “does not coincide with the question of practical function. The purpose-free (zweckfrei) and the purposeful (zweckgebunden) arts do not form [a] radical opposition . . . The difference between the necessary and the superfluous is inherent in a work, and is not defined by the work’s relationship—or the lack of it—to something outside itself.” 53 The laws of functionalism admitted no purposiveness other than the inherently necessary in giving objective form to the development of productive capacities. By giving free reign to the latter, functionalism made it possible to produce an autonomous form that converged toward revolutionary purpose, efficiency that elevated capacity, and internal necessity that could be projected as external freedom. Functionalism’s commitment to efficiency allowed the development of architectural form to align with the liberatory ideals of the Mexican Revolution. The struggle for housing, public education, and universal healthcare, were not intentional results (however abstract) of the functionalist premise of maximum efficiency; their historical credibility, nonetheless, congrued with the inner purposiveness (formalization, standardization, mechanization, and simplification) of functionalist architecture. In the context of post-revolutionary Mexico, the outward appearance of architecture’s inner purposiveness congrued, however briefly, with the struggle to overcome the realm of necessity. 54

A more radical formulation of the same problem was advanced by Juan Legarreta, another participant in the pláticas, in the hand-written “synthesis” of his talk: “—A people who live in shacks and round chambers, cannot SPEAK, architecture. / —We will build the people’s houses. /—Aestheticians and Rhetoricians – hopefully they all die – will discuss afterwards.” 55 Legarreta’s charge against the devotees of sentimentality and expressivity, instantiated the contradictory character of architectural works as “both autonomous and purpose-oriented:” 56 insensitive toward aestheticization (“We will build the people’s houses”) and, by reason of this very insensitivity, able to produce an aesthetic claim on the essentiality of form. This particularizing contradiction entails a distinct configuration of the problem of autonomy, where the elements of composition, arrangement, and structuration, i.e. of purposiveness, adhere to any consideration given to formalization. The pressing question during the 1933 pláticas, therefore, had less to do with political affinities (or neutralities) than with the assertion of aesthetic judgements: whether a building should be aesthetically judged according to its adherence to the inner logic of rationalization, or if, on the contrary, its ‘beauty’ should be measured in accordance with the creative competencies of the architect. 57

The parameters of the discussion and the conceptualization of autonomy they allow for vary significantly from the dimensions of the 1932 polemic. Whereas literary vanguardism’s claim to autonomy was carefully constructed around a rejection of political determinations (particularism, nationalism, statism, etc.) the pláticas de arquitectura corroborated that any autonomous assignations had nothing to do, at least not inherently, with an individual’s political affiliations (or lack thereof). The fundamental question, for O’Gorman as for Legarreta, did not proceed along the fault lines of nationalism and cosmopolitanism, nor was it delimited by the demands of political neutrality—a historical impossibility in a context where the state “assumed the responsibility for the creation of the financial institutions and for the infrastructure projects which were beyond the means of Mexican private enterprise.” 58 Technical architecture, the name O’Gorman gave to his functionalist program, was, rather, a formal synthesis between architecture’s assertion of autonomy, Mexico’s accelerated capitalist development, and the politico-ideological singularity that grew out from two decades of revolutionary struggle and mass mobilization and organization. By referring to the relation between functionalism’s inner purposiveness and the political arrangements of the national-popular state as congruent, I aim to bring historical particularity to bear on the question of autonomy, and move past the interpretive certitude in the “narrowing,” i.e. repressing proclivity of all things structuration, with an emphasis on the state form, whose dependency upon capital cannot be reduced to an immanent affection without concurrently refusing historicity.

Mexican functionalism’s espousal of the socialist demand for collectivization, I wish to conclude, poses a distinct challenge to commonplace assumptions about the antagonism between commitment and autonomy, politics and art, formation and speculation. This challenge is perhaps most clearly illustrated by the well-known episode involving Diego Rivera and his reaction to “Mexico’s first-ever functional house,” which O’Gorman built in Calle Las Palmas número

81 in 1929. 59 Upon inspection of the building, Rivera found it to be aesthetically pleasing despite having been strictly designed to be useful and functional. “In that moment,” wrote O’Gorman,

Diego Rivera invented the theory that architecture carried out according to the strict process of the most scientific functionalism, is also a work of art. And given that through the principle of maximum efficiency and minimum cost, a greater number of constructions could be built with the same effort, the project was of an enormous relevance for the quick reconstruction of our country, and therefore (according to maestro Rivera) the building was beautiful. 60

Functionalism’s principles of formalization (standardization, simplification, rationalization) had produced, in Rivera’s opinion, a building that was not only efficient but, because of its formal consistency, aesthetically worthy. The episode, if one chooses to abide by Rivera, 61 is revealing of how inconsequential the affinity between functionalism’s formalizations and O’Gorman’s political commitments was, since the house’s construction was not meant as a political or artistic statement, but rather as a truly architectural one. Likewise, the episode lends some perspective on the question of the opposition between the politico-economic and the aesthetic, since, according to Rivera’s appreciation, functionalism’s “strict process” did not hinder but, in fact, constituted the lever for the building’s aesthetic relevance. Rivera’s appraisement of the house opened the door to repurposing functionalism’s method for revolutionary ends. Elicited by the inner coherence of the building, such collectivist projection was, in Rivera’s opinion, what made the house beautiful. The possibility of repurposing functionalism’s method in such a way, however, did not follow spontaneously from the architect’s political commitments, but from the transformations in the social process of production that made it historically viable to see functionalism’s premises through, i.e. from the productive developments that made it possible to extrapolate functionalism’s formalizations beyond its self-legislating framework. Placing the emphasis on the development of Mexican capitalism rather than on the deceptively obvious interaction between O’Gorman’s functionalism and the socioeconomic projections of the national-popular state, it becomes easier not only to account for the architect’s refusal of his functionalist beginnings but, more importantly, to restore the possibilities of formalization to project historical alternatives to capitalist sociality.

In his account of O’Gorman’s disenchantment with functionalism, Luis E. Carranza notes that by 1936, “architecture had become, for him [O’Gorman], a ‘business,’ and functionalism, as a style, had become co-opted by developers who wanted to increase their profits with minimal economic outlay;” functionalism’s premises had been “ideologically commandeered” by the henchmen of capital, its “’internationalist’ guise and its ‘disruptive’ aesthetics made it appear as the architecture of socialism, while instead its logic of ‘maximum efficiency with the minimum work’ stated the productive and profitable value of such construction.” 62 Furthermore, O’Gorman’s sudden change of heart has been almost invariably presented alongside a critique of the Mexican state’s corruption of the ideals of the Revolution, offering the architect’s turn toward painting as an intellectual refutation of the immanent perils of structuration. This dominant interpretation, I argue, however accurate as a critique of the political integuments of Mexico’s peripheral capitalist development, tends to produce an interpretative solution that ends up mistaking capitalist armatures with formative installations.

The fact that functionalism’s formalizations became contemporized through capitalist parameters in post-revolutionary Mexico does not admit that the inner consistencies of such formalizations cannot congrue with radically different kinds of sociality. To think otherwise would be to erroneously immanentize violence in structuration and to capitulate before capitalism’s catastrophic lineaments. An alternative to such pronouncements, as Anna Kornbluh has argued, must commit “to structuration as such, tracing the radically essential, radically ungroundable installation of social order and pivoting that formal recognition into the opportunity for constructing new socialities, new constitutions, new orders of forms.” 63 Despite the ideological tug-of-war that ended up displacing functionalism from the catalogue of forms available to conceptualize social transformation in post-revolutionary Mexico, it strikes me that the fundamental consistency of its method advanced exactly this kind of radical commitment to structuration. The historical harmony between functionalism’s inner purposiveness and the necessity of social reedification therefore poses a forwarding challenge to the essentialization of unmaking as the ultimate vitalist gesture. In its manifold failures and experimentations, the ephemeral compenetration of theory and practice that I have been referring to as congruency instantiated for post-revolutionary Mexico the social necessity of social forms. The latter position amounts to an affirmation of use value over exchange value, a confirmation that “[e]very useful thing is a whole composed of many properties; it can therefore be useful in various ways. The discovery of these ways and hence of the manifold uses of things is the work of history.” 64 Forms can be repurposed. This is the lesson to be derived from functionalism’s historical congruencies with collectivization and accumulation. This is the kind of lesson that can hopefully open the door to contrive prolific roads toward just, livable social futures.

Pavel Andrade is an Assistant Professor of Spanish at Texas Tech University. His research and teaching focus on Mexican literary and cultural studies, 20th and 21st c. Latin American literature, theory of the novel, formalism, geocriticism, and hemispheric modernisms. His current research project examines the emergence of a countertopographical perspsective in the Mexican novel of the long sixties and its formal relation to the tumultuous reconfiguration of peripheral capitalism in the postwar era.

Notes:

-

1 Portions of this essay were presented at the Modernist Studies Association’s annual conference as part of a seminar convened by Antonio Córdoba, Ignacio Infante, and María del Pilar Blanco. I am thankful to everyone who participated in this event, to the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and generous comments, and to Tavid Mulder for the invitation to contribute to this special issue of FORMA. BACK

-

2 “La revolución ¡no hay que dudarlo! ha dejado atrás, en el desarrollo de su proceso sabio y atinado, el inútil y engañoso período destructivo, para entrar gallardamente en los ricos senderos de la reedificación.” José Mancisidor, La ciudad roja: novela proletaria (Xalapa, Veracruz: Editorial Integrales, 1932), 13-14. When referring to primary sources, I have included both the Spanish original and the English translation. Secondary sources are only quoted in translation. All translations are mine. BACK

-

3 “El momento es otro: ¡creador, edificante, optimista! Hay que inspirar confianza al capital para que la Patria prospere y engrandezca…” Mancisidor, La ciudad roja, 18-19. BACK

-

4 Raymond Williams, “The Politics of the Avant-Garde,” in The Politics of Modernism: Against the New Conformists (London and New York: Verso, 2007), 52. BACK

-

5 See Adolfo Gilly, La revolución interrumpida: México, 1910-1920: una guerra campesina por la tierra y el poder, 8th ed. (México: Ediciones El Caballito, 1977). BACK

-

6 In Utopías inquietantes: narrativa proletaria en México en los años treinta (Veracruz, Mexico: Instituto Veracruzano de la Cultura, 2008), Bertín Ortega notes that proletarian literature “proposed a partial, denunciatory, critical art, committed to a social class. Thus, while revolutionary culture and art were based on the unity and harmony among classes and on the presupposition of a consummated revolution, for some successful, for others failed, for others unfulfilled, and for others still in progress, ‘proletarian literature’ is based on the idea that the social revolution (the adjective sharply distinguishes it from what is known as the Mexican Revolution) had not yet occurred” (27-28). BACK

-

7 The movimiento inquilinario of Veracruz was a communist-inflected popular movement that, starting in 1922, staged a series of mass demonstrations and strikes (withholding rent) to protest the rising cost of housing and poor living conditions in the port city. The movement galvanized different groups, political organizations, and unions, leading to the creation of the Sindicato Revolucionario de Inquilinos [Tenants’ Revolutionary Union]. For an account of the emergence of the tenant movement see Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Bolcheviques: Historia narrativa de los orígenes del comunismo en México (Ciudad de México: Planeta, 2019), 202-208. For an analysis of Mancisidor’s choices in framing the 1922 tenant strikes, see Alfonso Fierro, “The Proletarian Commune in Veracruz: José Mancisidor’s La ciudad roja.” Hispanic Review 90, no. 1 (2022): 83-105. BACK

-

8 Such is, according to Gilly, “the bourgeoisie’s maneuver to present itself as the owner, representative, and beneficiary of the Mexican Revolution, of its tradition, and its perspective” (La revolución interrumpida, 402). BACK

-

9 See Luis Mario Schneider, Ruptura y continuidad: la literatura mexicana en polémica (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1975); Víctor Díaz Arciniega, Querella por la cultura “revolucionaria” (1925) (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1989); Jorge Aguilar Mora, Una muerte sencilla, justa, eterna: cultura y guerra durante la Revolución Mexicana (México, D.F.: Ediciones Era, 1990); Guillermo Sheridan, México en 1932: la polémica nacionalista (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1999); Aimer Granados, “La literatura mexicana durante la Revolución: entre el nacionalismo y el cosmopolitismo,” in Polémicas intelectuales del México moderno, ed. Carlos Illades and Georg Leidenberger (México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes-Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Cuajimalpa, 2008), 157–185; and Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado, Naciones intelectuales: Las fundaciones de la modernidad literaria mexicana (1917-1959) (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2009). BACK

-

10 For Granados, “the 1932 polemic over the directions of national literature allows for an interpretation of the origins of the [Mexican] Revolution’s cultural nationalism, which, through the arts and other mechanisms, imposed an idea of nation that at least certain literary intellectuals denounced as exotic and as a way of closing off the country to the universalist currents of culture” (“La literatura mexicana,” 158). BACK

-

11 “¿[L]a juventud literaria debe interesarse en la política? Creo, más bien, que la política . . . debe interesarse por la juventud literaria . . . Crear becas, ayudar a la realización de obras de interés general, instituir premios de poesía, de novela y de teatro, sería en México algo tan interesante para el espíritu mexicano como construir presas, abrir caminos y trazar puentes.” Gregorio Ortega, “Conversación en un escritorio con Xavier Villaurrutia,” compiled in Sheridan, México en 1932, 157. BACK

-

12 As Nicholas Brown argues in Autonomy: The Social Ontology of Art under Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), “[t]he development of actual works of art as self-legislating artifacts is a much more complicated story, progressing in fits and starts, discontinuous across artistic fields and national and cultural histories, sometimes appearing to emerge full-blown in the most diverse circumstances, only to disappear again, apparently without issue” (28). BACK

-

14 In “Commitment,” trans. Francis McDonagh, New Left Review, no. 87 (1974), Theodor Adorno argued that “[e]ach of the two alternatives negates itself with the other. Committed art, necessarily detached as art from reality, cancels the distance between the two. ‘Art for art’s sake’ denies by its absolute claims that ineradicable connection with reality which is the polemical a priori of the very attempt to make art autonomous from the real. Between these two poles, the tension in which art has lived in every age till now, is dissolved” (76). For an account of the notions of poetic and literary purity in the context of the 1932 polemic see Sánchez Prado, Naciones intelectuales, 106-107. BACK

-

15 For an account of the exclusion of communism from the ideological configuration of the post-revolutionary state and the formation of a socialist realist school of literature in Mexico see Iván Pérez Daniel, “Mirages of a Second Revolution: Mexican Writers and Socialist Realism (The Case of the Magazine Ruta, 1933-1935),” trans. Debra Nagao, in Ghosts of the Revolution in Mexican Literature and Visual Culture: Revisitations in Modern and Contemporary Creative Media, ed. Erica Segre, (Oxford, New York, and Berlin: Peter Lang, 2013), 93–116. BACK

-

16 Lorenzo Turrent Rozas, Hacia una literatura proletaria (Xalapa, Veracruz, México: Ediciones Integrales, 1932), ix. BACK

-

18 See Pérez Daniel, “Mirages of a Second Revolution,” 101. BACK

-

19 “Nuestra literatura es casi unánimemente burguesa . . . por su falta de ideología y organización.” Turrent Rozas, Hacia una literatura, xv. BACK

-

20 See Nicola Miller, In the Shadow of the State: Intellectuals and the Quest for National Identity in Twentieth-Century Spanish America (London and New York: Verso, 1999), 44. BACK

-

21 “Salvar los valladares. Ser torrente desbordado… Arrasar… Barrer… Atacar… Destruir.” Mancisidor, La ciudad roja, 188. BACK

-

22 “La decisión ha de ser terminante, categórica. Lucha radical que señale una firme orientación a las masas, o contemporización con los actuales sistemas opresores que nos enervarán con paliativos momentáneos. Aquella será el sacrificio aparente y edificante; ésta, la actitud sospechosa y explotada sobre cuya miseria se levanta el dorado porvenir de los traidores de la masa. La una nos empujará hacia el futuro; la otra nos encadenará al presente.” Mancisidor, La ciudad roja, 177. BACK

-

24 Sheridan, México en 1932, 57 (emphasis in the original). BACK

-

26 Jorge Cuesta, “La literatura y el nacionalismo,” compiled in Sheridan, México en 1932, 226–230. BACK

-

27 Jorge Cuesta, “Conceptos del arte,” compiled in Sheridan, México en 1932, 314-317. BACK

-

28 “[N]uestro movimiento fue auténtico y sigue conservándose limpio de toda contaminación, de toda corrupción.” Alejandro Núñez Alonso, “Una encuesta sensacional: ¿está en crisis la generación de vanguardia,” compiled in Sheridan, México en 1932, 114. BACK

-

30 In “La ruta integral: la literatura proletaria desde Veracruz,” Bibliographica 3, no. 1 (2020), Elissa Rashkin notes that “[i]n the first issue of Ruta (March, 1933), the text ‘Revolutionary Poetry in Mexico’ by José Mancisidor marks an even stronger break with the avant-garde of the [19]20s. The author harshly criticizes the poets who, according to him, had focused on the question of form, excluding ‘the masses’ by using a ‘language alien to their cultural possibilities,’ without proposing a revolutionary orientation in the content” (73). BACK

-

31 The result is an early instantiation of what Anna Kornbluh, in The Order of Forms: Realism, Formalism, and Social Space (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), refers to as “anarcho-vitalism:” “Formlessness becomes the ideal uniting a variety of theories, from the mosh of the multitude to the localization of microstruggle and microaggresion, from the voluntarist assembly of actors and networks to the flow of affects untethered from constructs, from the deification of irony and incompletion to the culminating conviction that life springs forth without form and thrives in form’s absence. Noting its characteristic horizon of an-arche, the ‘without order,’ we might deem this beatific fantasy of formless life ‘anarcho-vitalism’” (2). BACK

-

33 “In aesthetic theory, ‘commitment’ should be distinguished from ‘tendency’. Committed art in the proper sense is not intended to generate ameliorative measures, legislative acts or practical institutions—like earlier propagandist (tendency) plays against syphilis, duels, abortion laws or borstals—but to work at the level of fundamental attitudes.” Adorno, “Commitment” 78. BACK

-

34 Fredric Jameson, Allegory and Ideology (London and New York: Verso, 2019), 312. BACK

-

36 Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (London and New York: Verso, 1994), 292. BACK

-

38 Sarah Brouillette and Joshua Clover, “On Artistic Autonomy as a Bourgeois Fetish,” in Totality Inside Out: Rethinking Crisis and Conflict under Capital, ed. Kevin Floyd, Jen Hedler Phillis, and Sarika Chandra (New York: Fordham University Press, 2022), 206. BACK

-

39 “Just as stagnantly dangerous as psychologism is the absolutization of the dissent from formed relationality—institutions, standing formations, the state—into the messianic horizon of destituency that forestalls the constitution of new futures . . . Existing forms of sociality do not exhaust all possible socialities; confronting the grave wrongs—violence, subjugation, racialization—perpetrated by hitherto existing state formations need not culminate in wholesale indictments of all possible formalizations.” Kornbluh, The Order of Forms, 165. BACK

-

40 Caroline Levine, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015), 10. BACK

-

41 Georg Leidenberger, “‘Todo aquí es vulkanisch’: el arquitecto Hannes Meyer en México, 1938 a 1949,” in México a la luz de sus revoluciones, ed. Susan Deeds and Laura Rojas, vol. 2 (México: El Colegio de México, 2014), 501. BACK

-

42 Georg Leidenberger, “Las pláticas de los arquitectos de 1933 y el giro racionalista y social en el México posrevolucionario,” in Polémicas intelectuales del México moderno, ed. Carlos Illades and Georg Leidenberger (México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes -Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Cuajimalpa, 2008), 188. BACK

-

43 In Mexican Modernity: The Avant-Garde and the Technological Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005), Rubén Gallo notes that “[i]n Mexico, the use of cement and especially reinforced concrete, flourished in the 1920s. After nearly a decade of civil war, cement quickly emerged as the government’s preferred building material for its projects […] The motivation was not only practical—concrete buildings could be erected rapidly and inexpensively—but ideological. Architects sought a building material to represent the new reality of postrevolutionary Mexico, one that embraced a clear break with the past and particularly with the architecture of the Porfiriato . . . Inexpensive and modern, efficient and forward-looking, cement emerged as the perfect substance for building the new Mexico envisioned by the postrevolutionary government” (171-172). For an account of functionalism as an ideologically constructed aesthetic advanced by the cement industry see Luis E. Carranza, Architecture as Revolution: Episodes in the History of Modern Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 118-131. BACK

-

44 Leidenberger, “Las pláticas de los arquitectos,” 197. BACK

-

45 Tavid Mulder, “The Torn Halves of Mexican Modernism: Maples Arce, O’Gorman, and Modotti,” A contracorriente: una revista de estudios latinoamericanos, 19, no. 3 (2022), 276. BACK

-

46 In “Diego Rivera and Juan O’Gorman: Post-Revolutionary Architectural Anatomies,” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 28, no. 2 (2019), Lucy O’Sullivan writes: “The first significant interpreter of functionalism in Mexico was Juan O’Gorman, who read Le Corbusier’s manifesto [Towards an Architecture] in 1924 while studying under the architects Carlos Obregón Santacilia and José Villagrán García at the National School of Architecture. Influenced by Le Corbusier’s theoretical writings and these socially minded mentors, O’Gorman devised an architectural model based on the principles of cost-efficiency, hygiene, and spatial efficiency as a solution to the urban crisis. Dismissing the excessive ornamentation of Vasconcelos’s neo-colonial style as socially irresponsible, O’Gorman asserted that functionalism, which satisfied the material needs of the population and the economic necessities of national reconstruction, was the only viable architectural model for post-revolutionary society” (256). For a detailed analysis of the role of hygiene in O’Gorman’s architecture and its relation to state ideology see Susan Antebi, Embodied Archive: Disability in Post-Revolutionary Mexican Cultural Production (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021), 106-148. BACK

-

47 The pláticas were first published in 1934. I quote here from Carlos Ríos Garza, J. Victor Arias Montes, and Gerardo G Sánchez Ruiz, Pláticas sobre arquitectura: México, 1933 (México, D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 2001), 53. Subsequent references are cited in parentheses in the text. BACK

-

48 “Esta tesis romántica aprovechada hábilmente por la demagogia artística, crea el vocablo ‘arte por el arte’ y el vocablo plástico que consiste en creer que hay algo divino, que provoca un gusto especial, un gusto que acerca a la belleza absoluta, un gusto místico que eleva.” BACK

-

49 “En las exposiciones de cuadros tienen ustedes el único cuadro interesante que es la patente de la inconciencia y de la falsedad con una excusa muy buena, el arte superlativo, el arte libre, el arte, digamos claramente anarquista, sin base de ninguna clase, al igual (y pésame decirlo), es el cuadro que nos presentan las casas de las nuevas colonias el cuadro anarquista del Hipódromo, sin orden, sin ciencia y sin responsabilidades históricas de ninguna clase, con una muy buena excusa: somos artistas y sentimos.” BACK

-

50 “Sólo el artista reconoce al artista; sólo el mejor reconoce al mejor. Es por eso que el arte, el verdadero, es, según la expresión de Nietzsche, un arte para artistas. El público no lo disfrutará nunca.” Cuesta, “Conceptos del arte,” 315 (emphasis original). BACK

-

51 “Se podría pensar por lo antes dicho que niego valores indiscutibles humanos e históricos, que niego la estética como una de las manifestaciones de la inteligencia humana, pero la confusión podrá estar en considerar la estética como el medio y la finalidad de la obra, en vez de considerarla como su consecuencia.” BACK

-

52 Theodor Adorno, “Functionalism Today,” trans. Jane O. Newman and John H. Smith, Oppositions, no. 17 (1979): 31. BACK

-

54 In his Kindergarten Chats and Other Writings, (New York: Dover Publications, 1979), Louis H. Sullivan wrote on the relation between outward appearances and inner purposes: “The interrelation of function and form. It has no beginning, no ending. It is immeasurably small, immeasurably vast; inscrutably mobile, infinitely serene; intimately complex yet simple […] speaking generally, outward appearances resemble inner purposes” (43). BACK

-

55 “—Un pueblo que vive en jacales y cuartos redondos, no puede HABLAR, arquitectura. / —Haremos las casas del pueblo. /—Estetas y Retóricos – ojalá mueran todos – harán después sus discusiones.” Carlos Ríos Garza, et al., Pláticas sobre arquitectura, 53. BACK

-

57 Alfonso Pallares includes in the list of questions that guided the discussion: “¿La belleza arquitectónica, resulta necesariamente de la solución formal, o exige, además de la actuación consciente de la voluntad creadora del arquitecto?” [Is architectural beauty necessarily a product of the formal solution, or does it also require the conscious action of the architect's creative will?] Ríos Garza et al., Pláticas sobre arquitectura, 37. BACK

-

58 Jean Meyer, “Mexico: Revolution and Reconstruction in the 1920s,” in The Cambridge History of Latin America. Volume 5, c. 1870 to 1930, ed. Leslie Bethell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 193. BACK

-

59 “La casa que construí causó sensación porque jamás se había visto en México una construcción en la que la forma fuera completamente derivada de la función utilitaria. Las instalaciones, tanto la eléctrica, como la sanitaria, estaban aparentes. Las lozas de concreto sin enyesado. Solamente los muros de barro block y de tabique, estaban aplanados. Los tinacos eran visibles sobre la azotea. No había pretiles en la azotea y toda la construcción se hizo con el mínimo posible de trabajo y gastos de dinero.” [The house I built caused sensation because no one in Mexico had ever seen a construction where the form was completely derived from the utilitarian function. The installations, both electrical and sanitary, were visible. The concrete slabs were not plastered. Only the adobe block and brick walls had been smoothed. The water tanks were visible on the rooftop. There were no parapets on the rooftop, and the entire construction was built with the least possible expenditure of labor and money.] In Antonio Luna Arroyo, Juan O’Gorman: autobiografia, antología, juicios críticos y documentación exhaustiva sobre su obra (México, D.F.: Cuadernos Populares de Pintura Mexicana Moderna, 1973), 100. BACK

-

60 “Diego Rivera, en ese momento, inventó la teoría de que la arquitectura realizada por el procedimiento estricto del funcionalismo más científico, es también obra de arte. Y puesto que por el máximo de eficiencia y mínimo de costo se podían realizar con el mismo esfuerzo mayor número de construcciones, era de enorme importancia para la reconstrucción rápida de nuestro país y, por lo tanto, (según el propio maestro Rivera), le daba belleza al edificio.” Luna Arroyo, Juan O’Gorman, 102 (my emphasis). BACK

-

61 In “Diego Rivera and Juan O’Gorman,” O’Sullivan speculates about the construction of the Casa-Estudio that Rivera commissioned to O’Gorman shortly after the encounter: “Given Rivera’s belief in the socially transformative potential of rationalist architecture, it is likely that his commissioning of the San Ángel complex was partially an attempt to raise the profile of functionalism in Mexico. The project marked a pivotal moment in O’Gorman’s career, paving the way for his state collaborations and a series of other commissions from prominent political and cultural figures such as Frances Toor and Julio Castellanos” (259). BACK

-

64 Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy: Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (London and New York: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, [1867] 1990), 125. BACK