The Partition of the Pelado: Poverty, Art, and the Making of the PRI

This essay will examine the turn in recent scholarship in Latin American political and cultural theory to Jacques Rancière’s concept of the politics of the part who have no part. With the problem of poverty in their sight, many scholars see in Rancière’s thought a promising path for critiquing the region’s developmentalist politics and economics and its related politics of art and literature. 1 In Rancière’s writing scholars have seen a solution to what has been a constant challenge for those exploring the links between politics and aesthetics in the region: Latin American artists, authors and intellectuals have tended to reproduce an aesthetic tradition stemming from a lettered mestizo-criollo elite that, even with good intentions, inevitably leaves social hierarchies and the inequalities stemming from them intact. Rancière’s prominence in the field, then, is the response to what are ultimately logical questions. If someone were really interested in creating a world free of poverty, why would they turn to an aesthetic tradition that historically has been used to police and normalize behavior and deny access to jobs, land, political power and other material resources? What good are novels, images and stories if they have little relation to the poor’s demands to have their health, housing and infrastructure needs seen and heard? In short, if someone is in need of a real, material solution to their situation of poverty, why fictionalize it?

The importance of these questions and the reason Rancière’s politics of the poor (mistakenly, as we’ll see) seems like a productive response becomes clearer when read in relation to a paradigmatic example of this dynamic of politics and aesthetics in Latin America: Mexico’s politico-aesthetic tradition of mexicanidad (Mexicanism). This term expresses the notion of an essential Mexican identity embedded in ever-evolving processes of mestizaje and the historical continuity of a revolutionary heroism struggling against (but in the process often reproducing) the corrupt and exploitative colonial order. In this context, concepts like the coloniality of power, affect and the multitude have emerged as varying sorts of anti-hierarchical, horizontalist critique that might evade the inevitable reproduction of inequality that concepts like mexicanidad have often named. This emphasis on evasion—on not being trapped by a concept of hegemony or counterhegemony that would require the unrealizable task of postulating alternative totalizing orders of equality—is central to Rancière’s model of politics and has contributed to his importance for thinking politics and aesthetics in Latin America and other regions. However, as the following essay argues, Rancière’s horizontalist politics of eternal evasion do not so much provide a solution to the political-cultural logic that concepts like Mexicanism name, as reproduce their categories under new conditions. Indeed, the most significant claim of this essay is that Rancière’s model of the politics of the poor cannot critique Mexicanist thought because its categories are already part of Mexicanism’s structuring logic. This makes understanding the specificities of Mexicanist thought discussed below central for anyone interested in utilizing Rancière’s model of politics in other contexts.

Fundamental for Rancière is a redefinition of the concept of politics as an antagonistic encounter between two mutually constituting modes of being-in-common: one inegalitarian and one egalitarian. The first, which Rancière calls the order of police, is inegalitarian even when it ostensibly has egalitarian aims. This is so because the constitution of communities rests on what Rancière calls “the partition of the perceptible:” “an order of bodies that defines the allocation of ways of doing, ways of being, and ways of saying and sees that those bodies are assigned by name to a particular place and task.” 2 Police logic brings people together by organizing and processing who and what can appear in a given community as well as what they are allowed to do and say, and it gives to each “the part that is his due according to the evidence of what he is” (27). The problem is that this “partition of the perceptible” is always based on a miscount. There is always a part of the community who remain uncounted: those who are not seen or are heard only as “noise” and therefore have no part in the reigning “partition of the perceptible” (30). Rancière argues that what traditionally passes as politics (e.g., inclusionary efforts) is in reality nothing other than an extension of state control. In opposition to policing is Rancière’s conception of politics—the politics of the part who have no part—that “disrupts [the] harmony” (28) of existing counts, partitions and distributions by exposing the miscount. Politics, Rancière says, is at all times antagonistic to the miscount of police logic. It operates by “[making] visible what had no business being seen,” by “[making] understood as discourse what was once only heard as noise” and by “[shifting] a body from the place assigned to it” (30). This politics of movement evades the programmatic control of police logic by creating an uncontrollable “being-between: between identities, between worlds” (137) that is “never set up in advance” (32).

The politics of the poor as the always unseen and unforeseen egalitarian order that evades all programmatic logic is, as Gareth Williams has argued in his book The Mexican Exception, particularly important for the Mexican context. 3 In the century following the Mexican Revolution, Mexico became a society ordered by officially sanctioned narratives and images of revolutionary equality that justified the reconstruction of an unequal order organized around capitalist commodity production. Williams’s argument is that Rancière’s concept of the politics of the part who have no part can “pry open a space” (15) within the hierarchical and pedagogical Mexicanist police order established by Mexico’s one-party (PRI) state. One key example of the way this order operated emerges in his discussions of Alfonso Reyes. Through his approach to literature, Reyes, Williams argues, creates a politics characterized by “the never-ending establishment of aesthetic procedures . . . [that manage] systems for legitimizing” (89) the police order. 4 An ostensibly inclusive aesthetic tradition emerges instead as an iteration of the logic of the Mexicanist police state.

The solution for Williams, as it is for Rancière, lies in interruptions to any and all formulaic or procedural gestures of inclusion. These disruptions emerge through actions that are always unseen and unforeseen: “the murmurs of the incomprehensible, spontaneous, or irrational within the ordered field of the political” that “[announce] something other than [police] order” (14). Or, as Williams later puts it, a “delinquent counterpower to police order” becomes visible when the poor “make ill use of that order” (70). Williams says the best approximation to the poor’s politics of “ill” or non-normative “use” is the pejorative name given to the impoverished urban migrant: the pelado. 5 As one who takes what is not given, doesn’t do what he or she should, or does what he or she shouldn’t, the figure of the pelado enables Williams to adapt Rancière’s politics of the poor as a politics of “improper” use to the Mexican context (Rancière 123). Under this model of “ill,” “improper” or non-normative use, the pelado poses an unending political antagonism. “[T]he pelado,” Williams says, “is always a second or a third person” (70). It is premised on how one is seen or heard, that is, on the “partition of the perceptible” or particular structures of vision: “you are” or “he is” the lumpen threat who “wrongly” uses what is given. Because the pelado only emerges spontaneously—when he is seen as transgressing the state’s pre-established partitions—this figure is only intelligible as a name for formlessness: the unsanctioned use of social forms that cannot be seen or foreseen (and therefore never captured or managed) by the state.

However, as I argue below, the “ill use” that the pelado

and the poor “make” in their unplanned, spontaneous and non-normative

responses to inegalitarian partitions of the perceptible does not

challenge the underlying systemic inequalities of capitalism. To develop

this argument, I begin by exploring the work of an author who champions

the pelado’s creation of “ill use” as a model for politics and aesthetics: Agustín Yáñez. 6 Yáñez is a crucial figure for understanding the limits of Rancière’s

politics as aesthetics first of all because he writes explicitly against

figures like Reyes and in defense of the pelado’s

non-normative use. More importantly, however, he marshals the

non-normativity of the poor as a key conceptual piece of his work to

consolidate the PRI’s power as he served as one of its devoted

apparatchiks. 7 His politico-aesthetic model hinges on passing from a politics derived

from one kind of formlessness not set up in advance (the pelado’s

“ill use”) to another: the consumer’s ever-evolving use of the

commodity. In understanding how Yáñez’s aesthetics of poverty informs

his priísta

politics, it will become clear how the PRI’s politics of “permanent

revolution” prefigures Rancière’s politics of the part who have no part.

Beyond simple parallels, however, what Yáñez’s Mexicanism makes clear

is that the poor’s “ill,” “improper” or non-normative use articulates an

open-ended political model that can also be understood as a particular

kind of “artistic sensibility” (“Estudio” xxxiii): “the Baroque mode”

(xxxii). 8 Following Yáñez’s arguments, I go on to explain that the convergence of

Rancière’s politics of the part who have no part and the PRI’s politics

of the pelado

is premised on this Baroque politico-aesthetic sensibility. This

analysis will enable me to conclude with a reassessment of Reyes.

Premised on normative aesthetic judgments of meaning, Reyes’s literary

politics of poverty, I argue, suggests a productive path for turning

away from the mistakes of Mexicanism’s logic of poverty as an experience

of formlessness and the limits of Rancière’s aesthetics of politics

more generally.

Yáñez, Rancière, and the Mistake of Mexicanism

Yáñez most explicitly formulates his ideas on the poor’s non-normativity

as a political and “artistic sensibility” in 1940 when he published the

“Preliminary Study” to El Pensador Mexicano,

his anthology focusing on the work of José Joaquín Fernández de

Lizardi. This introductory essay is a defense of Lizardi’s aesthetic,

one that, notably, is positioned explicitly against Alfonso Reyes, whom

he names only as that “nice little old man” (v). Yáñez begins his

introductory study by summarizing the main points of an essay Reyes

wrote criticizing both Lizardi and critics who praise his approach to

art. 9 Yáñez does so in order to identify what he considers to be two central

problems in Reyes’s essay and to set up his defense of Lizardi’s

“artistic sensibility,” which Yáñez takes as a model for his own. 10

In his essay, Reyes judges Lizardi’s narrative harshly. Citing approvingly one of Lizardi’s early critics who notes his tendency toward haphazard sermoninizing in a simplistic and didactic style of writing, Reyes asserts that Lizardi demonstrates “poor taste” and completely abandons art through frequent use of “the language of the lumpen” (Reyes 174). 11 Though Reyes judges his use of indecorous language as a deficiency in Lizardi’s art, it was key to his immense popularity and led to his unmerited reputation as the wise “Pensador Mexicano.” This latter point is particularly important for Yáñez, who takes note of what he considers Reyes’s elitist and ultimately arbitrary observation that that “simple people . . . [are] unaware that [Lizardi’s] pseudonym derives . . . from the Spaniard, Clavijo,” who published the newspaper El Pensador, rather than being attributed to Lizardi’s lauded status as “el pensador mexicano”(Reyes 171). 12 For Yáñez, then, the first problem with Reyes’s approach to Lizardi is that he “disparages those [the poor] who would suppose that it was later generations who gave [Lizardi] the nickname ‘El Pensador’ because that’s what he was” (Yáñez v-vi). 13 This disrespect for the poor and how they receive Lizardi’s reputation and use his work connects to what Yáñez identifies as the second problem in Reyes’s essay: the dissatisfaction Reyes expresses with Lizardi’s aesthetic “defects” (vi) and abandonment of art, an assessment Yáñez characterizes as a product of what is ultimately an arbitrary set of “strict rules governing behavior” (vi). 14

For this reason, Yáñez spends the majority of the essay praising Lizardi’s “vulgar” or “lumpen realism” (xv). 15 If Reyes sees an abandonment of art in Lizardi’s decision to place on the page “the lowest people in society working in run-of-the-mill fashion just as we see them, speaking just like we hear them” (Terán in Reyes 174), Yáñez sees an “artistic sensibility” (xxxiii) that should be recovered. 16 By following Lizardi, artists could lead the country toward creating its own universalizable traditions instead of uncritically following predetermined formulas from Europe: “vulgar realism, lumpen realism . . . and critical realism fashion a path between what is and what should be” (xv). 17 What “vulgar” or “lumpen realism” does, Yáñez argues, is fashion a space between present inequalities—generated by “strict rules governing behavior”—and a world that overcomes them by demonstrating the reality of the promise of revolutionary equality. Rather than reproducing the existing “social divisions” (xix), Yáñez sees in the supposed “vulgarity” (xxviii) and “poor taste” (xviii) of Lizardi’s “lumpen realism” the possibility of disrupting the norms that govern those “social divisions.” 18 Moreover, Yáñez argues that “lumpen realism” takes as a starting premise the notion that there is no ground from which to sustain the notion that there is in Mexico “on the one hand, the clouds, the group of ‘respectable people,’ [and] distant from them, buried in a chasm, the ‘pelados’” (xx). 19 In short, Yáñez asserts that any social hierarchy in Mexico is “arbitrary, almost always” (xx). 20 As he goes on to point out, this “arbitrary” division between “respectable people” and “los pelados” remains in place because it is reproduced by the “artistic sensibilities” of people like Alfonso Reyes.

What Lizardi makes clear to Yáñez, then, is that “social divisions” primarily rest not on the inequalities of a system of production but instead on a hierarchy that polices who is allowed to be seen walking among “the clouds” and who must remain invisible, “buried in a chasm,” or, more generally, on a hierarchy structured by the attitudes people exhibit toward each other. That hierarchy, Yáñez argues, is structured by “decorum” [“la buena educación”], which is arbitrarily connected to “a certain series of formulas” (xxii). 21 “Respectability,” he says, should not be tied to “decorum,” which is a notion that only creates what he calls “the man of formulas, the man of habits” (xxii). 22 Instead, it must be tied to what is antagonistic to the “man of formulas,” the pelado: “the pelado experiences a discomfort within any and all predetermined practices, habits or formulas . . . he breaks with every type of tyranny; he desires to live as he pleases” (xxii). 23

The pelado as a haphazard disruption of what Yáñez also calls “prevailing habits and conventions” is a direct challenge to “the conservative, the man of status, the man of privilege, the man who exploits” (xx-xxi), and it is a term that can be tied equally to the artist and the poor. 24 This disruption, however, is not an arbitrary style but instead a politico-aesthetic practice:

a synonymy exists between “pelado” and “igualado” [one who asserts his or her equality], [because] ‘pelado’ is often used to address, insult, reproach or threaten anyone presumptuous enough to declare him or herself another’s equal. (xx-xxi) 25

For Yáñez, the pelado is marked by having others see and say that one is “making ill use,” that one is out of place, that one behaves outside the formulas of “decorum” that are used to exploit the poor and maintain privileges for the “respectable.” The importance of this non-formulaic presumption of equality and direct challenge to the pre-determined norms of “decorum” is not only that the pelado is out of his assigned place but also that he declares a new partition: he declares himself equal (“igualado”) in the moment of his own choosing.

In Yáñez’s reading, then, the term “pelado” names the accumulation of unplanned, spontaneous assertions of more egalitarian partitions in each and every era of Mexican history. Beginning with indigenous rebellions and spiraling out into an expansive historical reading of post-Independence Mexico, there is no coherent program emerging from the heterogeneous faces attached to the term “pelado.” Instead of naming a particular programmatic tradition, the actions are seen as “one-off” performances of an ever-evolving logic of equality. This meaning only materializes in specific moments of spontaneous assertions of equality and dissipates as a new order is established. As he notes, Hidalgo, Morelos, Guerrero, Santa Anna, Juárez, Porfirio Díaz, Madero, Carranza, Villa and Zapata were all called pelados, along with rebellious indigenous communities.

No one can aspire to do what the pelado does. This is so because there is no formula, system or program that can secure that a certain series of actions will be seen as an egalitarian “ill use” of the existing order. As Yáñez puts it:

the pelado is one who does not establish hierarchies or inequalities through use of language or conduct; the pelado . . . [is] any person who does not give conditions to or repress all spontaneous action, anyone who rejects the norms of “decorum,” and all in all, anyone who, finding him or herself assigned to a subordinate social position, attempts to assert him or herself as an equal . . . (xxi) 26

Yáñez’s

political model can be summarized as asserting that equality can

materialize through spontaneous action even when—or, perhaps better

said, especially because—it does not become an organizing principle. In

other words, in actions that are “never set up in advance,” the pelado

takes what is not assigned to him and creates unforeseen notions of

equality. Or to put it more clearly still, Yáñez’s politics of the pelado can be best understood as an exemplary expression of Rancière’s politics of the part who have no part.

As

noted earlier, Rancière’s conceptualization of politics is at all times

antagonistic to the miscount of police logic even when that police

logic was ostensibly egalitarian. This is because the supposedly

egalitarian order contains within it inequalities that could never have

been taken into account when it was designed because there are those who

were not seen and therefore were not allocated a part of the

community’s partitions and distributions. However, the task for

politics, according to Rancière, is never to demonstrate that the notion

of an “ideal people” who are completely equal (the “appearance” of

equality) is false when confronted with “the real people” who suffer

from varying forms of poverty within actually-existing partitions

(Rancière 88). Instead, if an action is political, it takes a founding

egalitarian logic as a starting premise and seeks “not to contradict

appearances but, on the contrary, to confirm them” (88). What is key is

that an “improper” use is seen and that spontaneous or unforeseen

actions are recognized as a “declaration [that] equality exists

somewhere” even if “inequality rules” (89). This enables the uncounted

to “invent a new place for [equality]” (89) by using particular

“moments, places, occurrences . . . [to] give place to the nonplace”

(89). For this reason, Rancière says, politics “is not opposed to

reality” but instead “splits reality and reconfigures it as double”

(99).

Rancière’s conceptualization of politics clarifies some of the more confusing aspects of Yáñez’s arguments regarding the pelado. As we saw above, Yáñez says the egalitarian logic of the pelado was seen in the actions of Emiliano Zapata but also in the actions of Porfirio Díaz. This makes sense only if we accept Rancière’s claim that what is crucial for politics—for “the declaration of equality” (Rancière 89)—is that an action is non-normative and does not contain within it any pre-conceived formulas or sets of prescriptions for a political transformation. As he says in Disagreement, “[t]he same thing—an election, a strike, a demonstration— . . . . may define a structure of political action or a structure of the police order” (33). In this sense, taking up Yáñez’s reading of the pelado, the most important aspect of politics in Mexico is not Porfirio Díaz’s decision to occupy the seat of power nor is it Zapata’s decision to never be found doing so. Instead, the point for Yáñez, as it is for Rancière, is not the action itself but instead its effects, how it is seen: to what extent it makes the miscount of the existing partition visible or audible.

For this reason, the political act or moment can never found an order: “every time . . . [there is] an act” that merits the name “politics” it is “always a one-off performance” (Rancière 34). If it forms the premise of “a social bond,” if it is “set up in advance” as a principle or procedure or formula, if it “aspires to a place in the social or state organization” then that egalitarian act becomes its opposite: a police logic focused not on egalitarian effects but on principles of organization (34). To the extent that it names that which can never be formalized into any thing beyond accumulated episodes in which the antagonistic, non-normative and egalitarian uses of the social can be glimpsed, the politics of the part who have no part manifests itself in Mexico in Yáñez’s politics of the pelado. This is the poor’s demand to reconfigure what he describes as the arbitrary division between “the clouds” and “the chasm.”

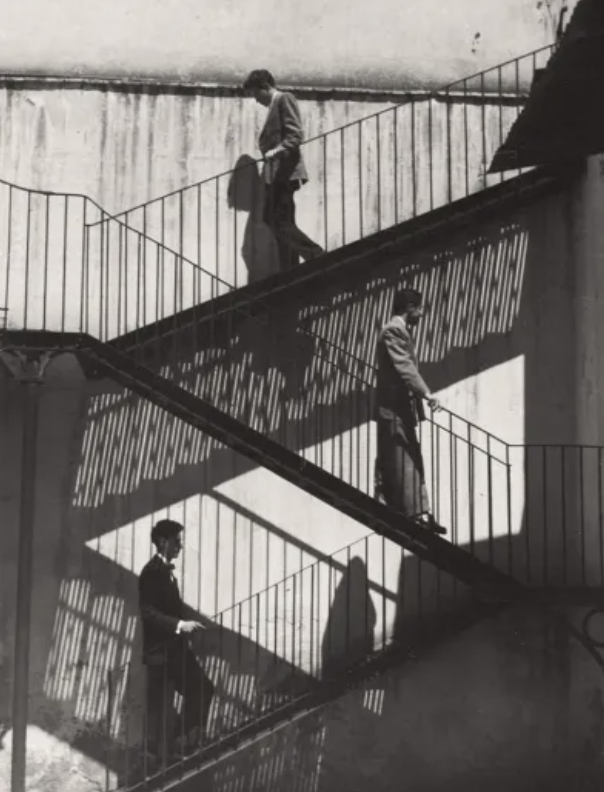

This,

of course, is what takes place in the first decades following the

Mexican Revolution as new inequalities emerged amid the pretensions of

egalitarianism enshrined in the 1917 Constitution. As postrevolutionary

art, cinema and literature reconfigured and made visible new

conceptualizations of equality in Mexico throughout the 1920s, there was

also an an inegalitarian political, economic and social order in

development. In this context, the poor developed spontaneous strategies

to meet their material needs and to allocate to themselves what was not

given. The poor’s “being-between”—the formlessness of those not taken

into account in Mexico’s postrevolutionary social order who

spontaneously and episodically materialize into disruptive declarations

of new egalitarian partitions—is what Yáñez has in mind when appealing

to the figure of the pelado who points to an equality that lies just over the horizon. The images Yáñez associates with the politics of the pelado

are always disruptive of the “arbitrary” norms that structure the

“social divisions” that facilitate the operation of the political and

economic system: the servant who “talks back to his employer,” the

politician who says “the indigenous and the poor are right” or the

writer who “tells the unvarnished truth and exposes corruption” (xxi). 27 These actions do “not establish hierarchies or inequalities through use

of language or conduct” (xxi) but instead are antagonistic to the

“hierarchies” and “inequalities” that language and “strict rules

governing behavior” make possible. 28 If it is possible to see now the convergence of Rancière’s politics of

the part who have no part and Yáñez’s conception of politics derived

from the pelado’s

making visible the poor’s non-normative use of language and conduct, it

is also possible to begin to see the mistaken conception of poverty

that underscores them both.

This

mistaken conception of poverty as the part who have no part is most

clearly articulated when Rancière asserts that “the solution to” the

economic inequality that “the class struggle” (13) names “would have

been found pretty quickly” (13) if material lack were the primary issue.

“The trouble,” he adds, “runs deeper” (14) than deprivation and

exploitation. It runs through the question of visibility and who can be

seen and heard. Rancière argues that the poor—those who have no part in

the existing “partition of the perceptible”—are included within “the

people” but cannot be seen as such: “the people are not really the

people but actually the poor, [and] the poor themselves are not really

the poor. They are merely the reign of a lack of position . . .” (14).

What Rancière is saying here is that the reason some members of the

community are not allocated their equal share—the reason there is

poverty—is because of an accounting oversight: they are not seen or are not heard.

In this model, poverty is not the result of a particular way of

structuring economic production but rather the result of “an order” in

which anyone and everyone is not treated as an “equal speaking being,”

“an order” that locates some “ways of doing, ways of being, and ways of

saying” in what Yáñez called “the chasm.” When poverty is conceived as

Rancière’s part who have no part or Yáñez’s pelados

“buried in the chasm,” its solution lies in the persistent demand to

reconfigure the partition to account for the oversight, to appeal to

what is heard only as “noise” or to see “what had no business being

seen.” This formulation is the mistake at the heart of Rancière’s

concept of the politics of the part who have no part, wherein the

solution to poverty and inequality is having one’s “ways of doing, ways

of being, and ways of saying” be seen as non-normative.

The

mistake is clear in Yáñez’s account of Mexico’s history of seeing the

egalitarianism of disruptive non-normativity. This model of poverty and

politics creates a situation in which there is no fundamental difference

between Porfirio Díaz and Emiliano Zapata. In particular “moments,

places, ocurrences” each was able to “give place to the nonplace”

(Rancière 89), that is, to reject “the norms of ‘decorum’” (Yáñez 21)

and be seen as the equality-demanding pelado. It is equally the case that in this model there is no fundamental difference between porfirismo and zapatismo.

They both name what would be for Rancière a police logic focused not on

egalitarian effects but on principles of organization that contain

within them unseen or unforeseen “hierarchies” and “inequalities” based

on language and “strict rules governing behavior.” Though “one kind of

police may be infinitely preferable to another,” Rancière says “[t]his

does not change the nature of police . . .” (31). And it also would not

change the nature of his understanding of politics, which is not the

proposal a specific program for equality but instead disrupting any and

all normative or programmatic understandings of equality in favor of the

poor’s non-normative use that makes episodically visible an equality

that lays just over the horizon. Any redistribution or reorganization of

the modes of economic production would necessarily rest on a miscount,

which must be made visible through an accumulation of the poor’s

disruptive uses of language and modes of conduct.

This, of course, is premised on the notion that, whether the system is zapatista or porfirista,

there will always be corruption, exploitation and poverty and that the

only solution is the poor’s episodic disruption through non-normative

use. If this is what Yáñez recovers from Lizardi for his Mexicanist

aesthetics, it is also what directs his bureaucratic activities in the

emerging system of the PRI. As Mark D. Anderson has pointed out, Yáñez’s

work within the PRI was largely based on his non-normative use of

language and notes that Yáñez thought of his politics as an open-ended

process that sought to make visible “a subterranean stratus that lies

far below the layers of reality” (85). 29 Citing a speech Yáñez gave while serving as governor of Jalisco,

Anderson explains the extent to which Yáñez’s politics of making the

country’s “subterranean stratus” visible—his politics of making “the pelados

buried in a chasm” seen and heard—functioned as an aesthetics:

“[governing] in reality is nothing more than the work of a novelist, of a

novelist who blends fiction into reality” (in Anderson 84). 30 This politico-aesthetic model in which fiction is open to reality and

reality open to fiction creates, in his view, a responsive model

antagonistic to both hierarchical “artistic sensibilities” and the

inequalities underscoring “political sensibilities.” 31 Just as Rancière sees “politics [as] aesthetic in principle” (58), so too does Yáñez view them as inextricable from each other.

It is for this reason that Lizardi is so important for Yáñez’s understanding of politics and aesthetics. Lizardi’s appeal to the disruptive “language of the lumpen” and his indecorous “poor taste” are premised on a leveling of hierarchies. What makes his aesthetics political is his ability to disrupt decorum by “[utilizing] whatever resources he deemed adequate: simple words, direct expressions, clichés . . . . [This is an] artistic sensibility, even though it escaped the formulas that rhetoricians prescribed” (xxxii-xxxiii). 32 Yáñez praises this ability to escape prescribed formulas and to make visible the fact that supposedly “respectable” language and conduct only lead to corrupted hierarchies that reproduce the inequalities that render the poor invisible. By utilizing the materials “he deemed adequate”—the “improper” or “ill use” of “simple words” or “clichés”—to produce his aesthetic work, Lizardi intervenes politically by crafting “the possible” out of “an impoverished existing reality” and gestures toward a path leading from “servitude under every order” to “a system of full economic, political and spiritual freedom” (xxxiv-xxxv). 33 In this way, what structures Lizardi’s writing, and what Yáñez seeks to recover from it, is a “communion with the people” (xxxiv)—the pelados “buried in the chasm”—which would enable a persistent or permanent reconfiguration of what it is possible to see and say and do: “[Lizardi’s aesthetics postulate] Mexico’s future, understood and desired as a never-ending, critical renewal” (xi). 34

This politico-aesthetic demand for reconfiguration, which Rancière calls the politics of the part who have no part and Yáñez calls the politics of the pelado, is not incompatible with what Christopher Harris has called Yáñez’s commitment to “permanent revolution” through an “ongoing process” that is synonymous with the PRI (131). 35 It is obviously the case, as noted above, that in Rancière’s model if an action “aspires to a place in the social or state organization” then any egalitarian act becomes its opposite: a police logic focused not on egalitarian effects but on principles of organization (34). But, as Ignacio Sánchez-Prado points out, when considered in relation to Mexican history, Rancière’s conceptual system is confronted by its “inability to discern the ‘police’ element always already embedded in any manifestation of politics.” 36 In other words, this “either/or” model does not account for politico-aesthetic projects like Yáñez’s, which attempt to postulate an order that contains within itself its own processes of political reconfiguration.

What Yáñez seeks in his “permanent revolution” is not a model that renders porfirismo indistinguishable from zapatismo, collapsing them into what Rancière would simply call differing police logics. Nor does he wish to make visible the contradictions between the heterogeneous actions and faces that were attached to or seen as the politics of the pelado. Instead, he seeks a model that, like Rancière’s politics of the part who have no part, does not “contradict appearances but, on the contrary, [is able] to confirm them” (Rancière 88), a model that can invent “the possible” within “an impoverished existing reality” but also allow new possibilities to emerge from within any and all reconfigurations. In short, he seeks an open-ended model in which the name attached to Mexico’s egalitarian logic can be, without contradiction, Porfirio Díaz and Emiliano Zapata. This open-ended politico-aesthetic model would be an iteration of the politics of the part who have no part. But it would also be an iteration of the “permanent revolution” that underscored the PRI’s Mexicanism as simultaneously politics and police.

The PRI’s “Baroque Mode” of Poverty, Politics, and Aesthetics

As we saw earlier, Rancière says that “[t]he same thing”—in this case

the poor’s disruptive, non-normative, egalitarian use of language and

conduct—“may define a structure of political action or a structure of

the police order” (33). However, as Sánchez-Prado points out, this

either/or structure fails to fully explain the Mexican case. Indeed, as I

have been arguing, through artist-politicians like Yáñez, the PRI can

simultaneously utilize its Mexicanist aesthetics of the poor’s

disruptive, non-normative, egalitarian uses of language and conduct—its

parallel to the politics of the part who have no part—to create the

“institutionalized revolution” (a police logic) and its “permanent revolution” (a political logic). In developing his defense of this “split” or “double” model of the pelado

in his essay on Lizardi’s poverty aesthetics, Yáñez attaches this

political logic to another name: “the Baroque mode” (xxxii). Notably,

the Baroque is an aesthetics of the disruptive fragment that

reconfigures and confirms appearances, a politics as aesthetics that,

like Rancière’s politics of the part who have no part, seeks “not to

contradict appearances but, on the contrary, to confirm them” (88). In

recognizing the confluence of Rancière’s politics-police model with the

Baroque politico-aesthetic sensibility, it is possible not only to

understand the contradictions at the heart of the PRI’s Mexicanism but

also to see what is at stake in pursuing a politics premised on the

mistake common to both models: the conception of poverty as an

experience of formlessness (the “lack of position” or life “in the

chasm”).

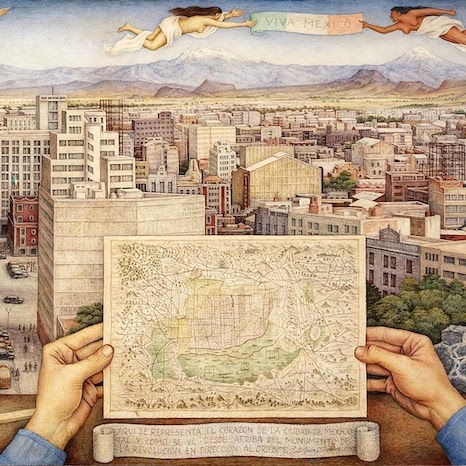

In

recovering Lizardi’s “artistic sensibility” against the ways that Reyes

“disparages” the poor’s enthusiasm for Lizardi’s supposed aesthetic

“defects,” Yáñez asserts that “the aesthetic of el Pensador” is without a

doubt marked by an “architectural influence” (x) represented by the

structures that populated Tepotzotlán, Taxco and Mexico City. Yáñez

identifies the key aspects of Lizardi’s aesthetic as “[utilizing]

whatever resources he deemed adequate: simple words, direct expressions,

clichés” in an “artistic sensibility” that “escaped the formulas that

rhetoricians prescribed” (xxxii-xxxiii). That “sensibility”—“the style

of el Pensador”—emerges from the relation he sees between figures in the

city’s plazas—“the unemployed [who] take in the sun and beggars [who]

implore passersby on the street”—and those in its buildings: “the

plethora of images and adornments that populate Baroque retablos and façades . . . . in which hundreds and hundreds of figures communicate hundreds and hundreds of moral lessons” (x-xi). 37 What we see in Yáñez’s account of Lizardi is an appreciation for the

poor’s spontaneous “ill use” of public space as both a parallel to the

figures in Baroque retablos

and a model for the “never-ending renewal” that articulates “Mexico’s

future.” The “one-off” performance—the unemployed loafing in the plaza,

for example—is simply one among “hundreds and hundreds of moral

lessons,” in which anyone and everyone who, in “finding him or herself

assigned to a subordinate social position, attempts to assert him or

herself as an equal.” Each of these “ill” or unforeseen uses of language

or conduct is not premised on a pre-determined program or utopian plan

of social transformation. Instead, they are developed by the poor as

spontaneous strategies to meet their needs for survival.

Yáñez’s adaptation of this “Baroque mode” that is the serial accumulation of “one-off” articulations of equality is perhaps most evident in his novel Ojerosa y pintada: la vida en la Ciudad de México (1959). 38 This text is a collection of episodes that stitches together something like a collage of the city as seen by the working poor, in this case, a taxi driver working a double shift transporting a heterogeneous group of passengers to various points within the capital. Though it is written from the halls of power—Yáñez composes it during the second half of his sexenio as governor of Jalisco—he still pursues the politics of the pelado: to make visible those “who talk back to their employer,” “attempt to assert themselves as equal” and that disrupt the “arbitrary” sets of “decorum.” For example, just as the cab driver is beginning his second shift, a formerly aristocratic family hires him for two hours at a set price, and he hears them denigrate how the poor have disrupted and reconfigured social life:

They spoke of the lumpen. Those miserable wretches, those filthy beggars, who don’t know how to treat others with the respect they’re due. They have all become impossible. Servants and doormen. Even the simplest messenger boy. Presuming equality . . . . Rejecting decorum as the norm. This is now democracy. (1035) 39

This former ruling class expresses the reigning police logic of the nineteenth century (porfirismo) and rejects the persistent political logic of those who now assert themselves as equals. It is their rejection of this egalitarian logic—the pelados’ disruption of “respectability”—that leads them to refuse to pay the taxi driver what he is owed after they surpass the agreed-upon two hours. The taxi driver refuses to be cheated and demands payment but receives only a portion of what he was owed and the curt reply that he is a “pelado” (1036).

If in this sequence the taxi driver is seen as the disruptive pelado,

it also demonstrates the extent to which he is newly emblematic of the

postrevolutionary “norm.” If the working poor whom the wealthy see as pelados

are also what “is now democracy,” that is, the reconfigured police

logic, Yáñez’s point is that the revolution cannot end there. The logic

of equality is unfinished, open-ended and must be persistently disrupted

and reconfigured. For example, after his encounter with the wealthy

passengers above, an indigenous campesino,

who had already been refused other modes of transport to take his

onions to market, approaches the taxi driver to negotiate a low fare.

The driver refuses, fearing the way future passengers may react to the

smell the onions would leave behind in his cab. Later, when again

refusing to carry another street vendor, the taxi driver repeats to

himself that he is not acting with “ill will or disdain if I have not

been able to serve the poor” (1127). 40 Instead, he is operating from the simple fact that in what is “now

democracy,” “first comes number one, in this case me, and then number

two” (1127). 41 What Yáñez suggests here is that the politics of the pelado

must be understood as an “ongoing process,” the “permanent revolution”

that must continue to accumulate egalitarian reconfigurations, even as

it fails to live up to them.

Yáñez emphasizes the importance of this process in the encounters that bookend the novel. At the novel’s beginning, the driver has an extended conversation with a poor, malnourished, adolescent factory worker from Peralvillo. What strikes the cab driver during their conversation is the way that the boy demanded respect from the foreign owners of the factory where he worked. They sought to pay him very little as a child porter because his malnourishment made him appear to be only 10 or 12, though in reality he was much older. Rather than following the norms and “decorum” set up by the way they saw him, he, like Yáñez’s pelado, did what he wanted: using “some discarded bricks” (987), he demonstrated his painting abilities, which led to higher pay and his being seen with respect. The boy’s pelado-like actions return in the final pages of the novel as the taxi driver remembers the recently deceased General Robles. Recalling this “immaculate revolutionary” who “[was] driven by justice,” “could recognize his mistakes” and “understood himself as an equal of his subordinates” (1133), Yáñez’s taxi driver sees the “ongoing process” of the “permanent revolution” that the politics of the pelado names: 42

in his neverending struggle, [Robles] demonstrated what can be achieved with the resolve and good faith efforts of an uneducated peasant, an origin that arrogant inhabitants of the capital never let him forget . . . . [the boy from Peralvillo] most certainly will overcome, just like the general. (1134) 43

Contemplating

the prejudicial gazes of the capital city’s elite—the postrevolutionary

“partition of the perceptible” that governs what one can see and say

and do—Yáñez has his taxi driver fold the story of the young,

malnourished factory worker into Robles’s story of non-normative use of

existing social hierarchies in the name of equality. In other words,

Yáñez proposes an open-ended process in which one does not take one’s

assigned position within the existing hierarchy: neither seeing oneself

as superior nor having others see one as inferior, a dynamic that

generates the heterogeneous faces of the pelado. 44 This is, of course, what Yáñez has in mind, as the taxi driver

incorporates other passengers, such as migrant construction workers from

Guerrero and Oaxaca, into “the same process” (1134). 45 The function of the “immaculate” general, then, is to connect all of

those who passed through the taxi—as well as those who were unable to do

so—to the non-normative logic of equality that the politics of the pelado

names. Yáñez’s poverty aesthetics makes this political logic visible as

part of the “permanent revolution” within the PRI’s “institutional

revolution:” a persistent reconfiguration that gestures toward an

equality just over the horizon that will be invented again and again.

In this sense, we can see Ojerosa y pintada as paralleling the “Baroque mode” of aesthetics Yáñez suggests are the product of Lizardi’s encounter with the poor’s use of the plaza and the “hundreds and hundreds of moral lessons” in Baroque retablos. The “immaculate” General, the unemployed migrant construction workers, the malnourished factory worker, the cab driver: they all accumulate as disruptive reconfigurations of how the poor populating the streets of the capital are seen. And Yáñez’s decision to highlight the presence of the indigenous street vendors denied transportation makes clear the Revolution’s disruptive demand for equality is not complete and must remain open-ended, prepared to reconfigure itself to see indigenous street vendors differently and to do so again when faced with future disruptions, whatever they may be. 46

This

open-ended demand to confirm an illusory ideal when it is disrupted by

unseen or unforeseen elements, as I have argued elsewhere, is a Baroque

disposition. 47 Under the Baroque’s politico-aesthetic conception of the social, there

can never be a “literal unity of material and illusion” (“Consuelo’s”

448) in much the same way that Rancière’s politico-aesthetic model

asserts that any egalitarian “partition of the perceptible” is

inevitably based on a miscount. Similarly, in the Baroque there is a

“repeated process of substitution and recreation that takes place in the

mind and on the body of a particular kind of beholder” (“Consuelo’s”

448), one who can “confirm” rather than “contradict” the appearance of

that illusory order, paralleling what Rancière identifies as the task

for politics. This is what Yáñez seeks in his politico-aesthetic model

of “permanent revolution” driven by the logic of the pelado

and his poverty aesthetics. His bureaucratic activity can build the

PRI—“[r]ejecting decorum as the norm”—while his aesthetics disrupt the

PRI, modify it, reconfigure it, and gesture toward an equality just over

the horizon.

This,

of course, is the problem. The “Baroque mode” that structures Yáñez’s

politico-aesthetic model, which, as I have been arguing, finds a

contemporary parallel in Rancière’s politics of the part who have no

part, also underscored what Bolívar Echeverría has called Latin

America’s first modernity built by a conservative criollo elite and the Catholic Church. 48 The Baroque functioned not just as a politico-aesthetic logic that

justified the Conquest (the incipient police logic, in Rancière’s

terms). It also, and just as importantly, operated as the logic of a

“counter-Conquest,” what Rancière would call a political logic of

“being-between” and what Echeverría called the mode of cultural mestizaje

through which life before the Conquest (non-capitalist forms of life)

managed to find a way to survive the violence of the Spanish state. 49 This does not mean the proposal for a counter-hegemonic political order but instead “a specific proposal to live in and with capitalism” (576). As a “‘savage’ cultural mestizaje”

(228) that was never “planned but rather [was] forced into being by the

circumstances at hand” and therefore “the result of a spontaneous

strategy of survival” rather than “the fulfillment of a utopian program

of action” (228), Echeverría’s model, which emphasizes these “processes

[as] unfinished and unfinishable” (228), possesses ample parallels with

Rancière’s thought. 50 But as Sánchez-Prado suggests, Echeverría’s model accounts for the

paradoxes in Mexico in which every articulation of a political logic of

equality contains within it the logic of police. For this reason,

Sánchez-Prado suggests that we “claim Rancière’s calls for horizontalism

as [our] own” (“Limitations” 381) by turning to Echeverría, whose

“Baroque ethos” is a model that also “followed the same rupture with Althusserian Marxism” (“Limitations” 381).

However,

as I have already begun to suggest, this would be a mistake. It very

well may be possible, as Sánchez-Prado proposes, that there are certain

advantages to using Echeverría instead of Rancière. However, an appeal

to Echeverría does not address what is the fundamental problem located

at the center of both Mexicanism and Rancière’s model: the conception of

poverty as an experience of formlessness. If the “institutionalized

revolution” is the problem—indigenous vendors are not seen as meriting a

ride so that former aristocrats will not be bothered by the lingering

presence of their wares—the “permanent revolution” is the solution:

making visible non-normative, disruptive uses of language or conduct and

moments when “ill use” is possible. The mistaken conception of poverty

shared by these models means that the only solution to poverty would be,

as Echeverría puts it when describing the Baroque ethos, to persistently develop new “proposals” to live “in and with capitalism,” rather than proposals to overcome it.

As

a PRI-ist bureaucrat who governs like a novelist with a Baroque

disposition, “Mexico’s future,” for Yáñez, is “understood and desired as

a never-ending, critical renewal,” and it is structured by the promise

of continuous repetition of the poor’s ever-inventive non-normative uses

of language and conduct. Because, Rancière says, nothing can “change

the nature of police” (31), the politics of the part who have no part

can only promise something paralleling Yáñez’s “permanent revolution”

within the PRI: an unending series of “one-off” political acts that

reconfigure what it is possible to see and say and do. In this sense, it

is Rancière who gives us a model in which the name for equality can be,

without contradiction, Porfirio Diaz and Emiliano Zapata. In the “permanent revolution,” there will always be corruption, exploitation and poverty: porfirismo and zapatismo

are simply orders of police, repressive in their own way, containing a

part (the poor) who are not seen or heard. The acts that set them into

motion, however, can be recovered for a political logic: the moment when

they were seen as the pelado’s “ill use.” This politico-aesthetic model of the pelado’s “permanent revolution” can live “in and with”

and indeed drive the consolidation of the PRI’s “institutional

revolution” as what Rancière would call a “preferable police.” What

makes it preferable to porfirismo

is not a demand to bring exploitation to an end, to redistribute land

or to nationalize additional industries, which could only be connected

to a police logic with goals premised on miscounts and outcomes set up

in advance. Instead, Yáñez’s open-ended politico-aesthetic model hinges

on making it easier to see non-normative use, that is, to see those not

allocated their share. In this way, the Baroque disposition of his work

on behalf of the PRI is not premised on actually being able to unify

“impoverished existing reality” with the illusory promise of

revolutionary equality: no order can do that. Instead, his aesthetics of

poverty and his politics of the pelado make the poor’s non-normativity seen so that equality can be glimpsed over the horizon.

As Yáñez envisions it, the factory worker does not want state-provided medicine for his sick mother or guaranteed access to sufficient food but instead to be seen as a body capable of doing a job that a malnourished adolescent shouldn’t be able to do. Likewise, the indigenous street vendors do not want land reform but instead to be seen as contributing to economic activity in bringing their goods to market rather than as a drag on others’ earning potential. In other words, this focus on how the poor are seen becomes a question about their relation to the market, which is structured by certain expectations of language and conduct. It is possible to see, then, how a conception of the “permanent revolution” focused on one kind of formlessness not set up in advance (the pelado’s “ill use”) seamlessly transitions to another: the “permanent revolution” as the market’s ever more efficient response to the innumerable uses and demands consumers will generate.

From Yáñez’s “Baroque Mode” to Reyes’s Normative Aesthetic Judgment

These series of contradictions in the politico-aesthetic model of mid-century Mexicanism—the logic of equality as Porfirio Díaz and Emiliano Zapata, the “institutional revolution” and the “permanent revolution,” the ways the poor use language and conduct and

the ways consumers purchase on the market—make understanding poverty

fiction important for a politics seeking to address the realities of

poverty. Those contradictions are enabled by a “Baroque mode” of

politics premised on structures of vision: the spontaneous strategies

the poor developed so that non-capitalist forms of life can manage to

survive “in and with

capitalism.” And as I have argued above, this can lead to the

contradictions that produce the PRI and the Porfiriato. For this reason,

it is important to analyze works that recognize this mistaken

conception of poverty by solving the aesthetic problem—the reduction of

art to its effects on viewers’ ways of seeing—that makes that mistake

possible, a task that returns us to Reyes and a corrective to the

mistakes embedded in the Baroque disposition of Yáñez and Rancière. 51

As

I noted above, Yáñez develops his politico-aesthetic model in explicit

rejection of Reyes, who, Yáñez maintains, “disparages” the poor’s

non-normative use of Lizardi, seeing him as the wise “Pensador Mexicano”

rather than understanding its meaning. If we return to Reyes’s essay,

however, that comment is simply one instance of a broader phenomenon in

Mexico that Reyes seeks to critique. His essay begins, for example, not

by “disparaging” the poor but instead by rejecting Lizardi’s prominence

in the two-volume Antología del Centenario

(1910), an anthology of Mexican literature created under the direction

of Justo Sierra by Luis G. Urbina, Pedro Henríquez Ureña and Nicolás

Rangel and published on the occasion of the country’s centennial. Reyes

premises this rejection on the fact that Lizardi’s reception and

reputation has very little to do with the “artistic value” (169) of his

literary production and is premised instead on its disruptive effects in

political and economic spheres. 52 As an example, Reyes cites an episode in which El periquillo sarniento

was censored “because it contained an attack on slavery” (171) and its

price “on the market” skyrocketed: “from that moment on, [the novel

contained] something like a martyrdom for freedom; it suffered for the

ideals of the people” (171). 53 What Yáñez understands as Reyes’s “disparaging” view of the poor is,

instead, part of a broader critique in which Reyes rejects reducing an

artwork’s value and meaning to the mandates of the market or the whims

of political structures.

What

Yáñez misses, then, is that Reyes is attempting to confront and move

beyond structures of vision that reduce art and its politics to the

effects that it produces. As Reyes notes, this latter model can be

equally understood as the poor’s “ill use”—or misunderstanding—of the

meaning of “el Pensador Mexicano” but also as the ever-increasing price

of his volumes on the market. What Reyes proposes is to disregard market

effects and popular use to focus instead on understanding the meaning

of Lizardi’s poverty aesthetics and to reach aesthetic judgments about

them. In rejecting this distinction, Yáñez arrives at his

politico-aesthetic model, which, like Rancière’s politics of the part

who have no part, can have no fundamental principle that articulates a

difference between actions so long as they are seen or heard

as disruptions of inegalitarianism. In his insistence on assessing

Lizardi in terms of his “artistic value” rather than the effects of his

disruptive appearance in popular use or in the market, Reyes points to

an alternative path for a literary politics of poverty.

This possibility becomes clear when considering Sánchez-Prado’s essay on Reyes’s importance in the wake of cultural studies. Describing Reyes’s broader intellectual project in ways that parallel the early critique of Lizardi’s poverty aesthetics, Sánchez-Prado makes the following observation:

the deeply-rooted politics of Reyes’s work [is] a politics that escapes all facile modes of praxis and the mistaken belief that the intellectual functions as the absolute redeemer of the poor or as a designer of immediately achievable utopias . . . (“El deslinde” 70) 54

Reyes proposes a model in which the focus is not on particular modes of being seen

nor in assigning to the intellectual or artist privileged roles as

either “martyrs for freedom” or the sole designers of redemption.

Instead, Reyes insists on understanding the tradition in which a

particular work was developed in order to move beyond it: to identify

and understand, to confront and overcome political and aesthetic

problems in a given historical moment.

It

is here, in re-conceptualizing Reyes, rather than in thinking Rancière

for Mexico through Echeverría, that Sánchez-Prado points to a real

solution to the paradoxes of Mexicanism that, I have argued, are

premised on a mistaken conception of poverty. While Reyes questions and

rejects a privileged place for disruptive non-normativity that appears

in market effects or popular use, he also does not advocate that critics

intervene to “prescribe where beauty is” (“El deslinde” 84). 55 Instead of “formulas” and “habits” that set up in advance what a

critic’s conclusion should be, Reyes advocates that critics intervene

politically with judgments that, as normative, universal claims, may be

right or wrong. This, Sánchez-Prado argues, is the promise of Reyes’s

aesthetics as politics: normative aesthetic judgments “maintain the

cultural resistance of the literary in its specificity” (84). 56 What Sánchez-Prado means by this is that “the literary”—the work of art

that disregards pre-determined formulas—can appear in a variety of

forms. In this way, the normative model of meaning and aesthetic

judgment that Reyes advocates remains open to historical realities that

pose problems that require aesthetic solutions, and it places the

responsibility on the beholder to recognize, understand and, rightly or

wrongly, interpret its meaning and its politics.

What Reyes provides, then, is an alternative to the “Baroque mode” of politico-aesthetic models like Yáñez’s—which made the order of the PRI’s market logic—and like Williams’s Rancière-reliant model, which proposes the “Baroque mode” as a way to disrupt and reconfigure market logic. As I have argued, these latter models are premised on a mistaken conception of poverty. This understanding formulates poverty as an experience of formlessness (the “reign of the lack of position” or life “buried in the chasm”) that can only become intelligible through the disruption of normative modes of language and conduct through uses that are seen as “improper” or “ill” placed. Reyes advocates a rejection of these beholder-focused models in which what matters is the effects on our modes of seeing and hearing. What the historical case of Mexico tells us is that if we are to create a path to a poverty-free world, we cannot proceed (as many do today) from an understanding of poverty as an experience of formlessness. Instead, by attending to the normative historical “specificities of the literary,” by recognizing, understanding and, rightly or wrongly, interpreting the aesthetics of poverty fiction, we can attend to the meaning of the politics of aesthetic forms to accept or reject them, to be able to contradict them rather than simply confirm them. In so doing, we can postulate a politics that understands and seeks to solve the historically specific forms of deprivation and exploitation and reject the “Baroque mode” of “permanent revolution” in which there will always be poverty, corruption and exploitation and only illusions of equality that must be recreated (or reconfigured) over and over again. What Reyes tells us is that we are not condemned to the way political leaders and market actors see or don’t see us: we can intervene politically with normative judgments that can demand material changes for all.

Stephen Buttes is Associate Professor of Spanish at Purdue University Fort Wayne. He is the author of Poverty and Antitheatricality: Form and Formlessness in Latin American Literature, Art, and Theory (Rutgers University Press, 2025). He is Editor-in-Chief of the peer-reviewed journal FORMA: A Journal of Latin American Criticism & Theory (formajournal.org). With Dianna C. Niebylski, he is editor of Pobreza y precariedad en el imaginario latinoamericano del siglo XXI (Cuarto Propio, 2017). His work on politics and aesthetics has appeared in a variety of journals and edited volumes, and his writing on teaching has most recently appeared in Approaches to Teaching the Works of Jorge Luis Borges (Modern Language Association, 2025). His current projects focus on the relation between artworks and wetlands and on the intersections between debt crises and the climate crisis.

Notes:

-

1 For one of the best overviews of the field and the resulting “deadlock of resistance,” see Abraham Acosta, Thresholds of Illiteracy: Theory, Latin America, and the Crisis of Resistance (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014). See also Eugenio Di Stefano and Emilio Sauri, “Making It Visible: Latin Americanist Criticism, Literature and the Question of Exploitation Today,” nonsite.org 13 (2014); Charles Hatfield, The Limits of Identity: Politics and Poetics in Latin America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015); Eugenio Claudio Di Stefano, The Vanishing Frame: Latin American Culture and Theory in the Postdictatorial Era (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018); and New Approaches to Latin American Studies: Culture and Power, ed. Juan Poblete (New York: Routledge, 2018). BACK

-

2 Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, trans. Julie Rose (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 29. BACK

-

3 Gareth Williams, The Mexican Exception: Sovereignty, Police, and Democracy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). BACK

-

4 For more on Justo Sierra, see Richard Weiner, Race, Nation, and Market: Economic Culture in Porfirian Mexico (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2004). BACK

-

5 See Samuel Ramos, El perfil del hombre y la cultura en México (Barcelona: Espasa Libros, 2012). BACK

-

6 Agustín Yáñez, “Estudio preliminar,” in El Pensador Mexicano (Mexico City: UNAM, 1962). Roger Bartra briefly discusses Yáñez’s essay in his famous reflection on mestizaje. See Roger Bartra, The Cage of Melancholy: Identity and Metamorphosis in the Mexican Character (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 91. BACK

-

7 See Mark D. Anderson, “Agustín Yáñez’s Total Mexico and the Embodiment of the National Subject,” Bulletin of Spanish Studies 84, no. 1 (2007): 79-99; and Christopher Harris, The Novels of Agustín Yáñez: A Critical Portrait of Mexico in the Twentieth Century (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2000). BACK

-

9 “un buen viejecito.” For Reyes’s essay, see Alfonso Reyes, “El Periquillo Sarnierto y la crítica mexicana,” in Simpatías y Diferencias: Tercera Serie. Obras completas, Tomo IV (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1956), 169-78. BACK

-

10 For Yáñez on parallels between his aesthetics and Lizardi’s, see Emmanuel Carballo, Protagonistas de la literatura mexicana, 4th ed. (Mexico City: Porrúa, 1994), 329-30. BACK

-

12 “la gente vulgar . . . ignora que [su] seudónimo deriva . . . del español Clavijo.” BACK

-

13 “se burla de quienes suponen que la posterioridad atribuyó al embozado el mote de Pensador porque lo era.” BACK

-

14 “tiene sus defectos y olvida las reglas del estricto comportamiento.” BACK

-

16 “las peores gentes de la sociedad obrando ordinariamente según las vemos, hablando según las oímos . . .” BACK

-

17 “el realismo grosero, canalla . . . y el idealismo progresista fijan el

camino entre el ser y el deber ser.” Yáñez calls his this “path” between what is and what should be (“el idealismo progresista”) a “critical portrait” or “critical realism.” See Carballo 330. BACK -

18 “las divisiones sociales”; “vulgaridad”; “mal gusto.” BACK

-

19 “por un lado las nubes, el grupo de ‘las personas educadas’, [y] distantes, un abismo, de los ‘pelados.” BACK

-

21 “cierto conjunto de formulas.” For an account of “la buena educación” and poverty in a contemporary Latin American context, see Dianna Niebylski, “Gramáticas capitalistas, retóricas contrahegemónicas y la prensa obrera chilena: Mano de Obra de Diamela Eltit,” in Pobreza y precariedad en el imaginario latinoamericano del siglo XXI, eds. Stephen Buttes and Dianna Niebylski (Santiago: Cuarto Propio: 2016), 415-457. BACK

-

22 “[estos] mecanizan la conducta y reducen la vida al ejercicio de ceremonias, algunas exóticas, inasimiladas, lo que acentúa el carácter falsario de quienes confunden y practican la ‘decencia’ como ‘buena educación’ como ‘urbanidad’, la ‘urbanidad’ como ‘cortesía’ . . . Por este camino llegamos al hombre de fórmulas, de hábitos . . .” BACK

-

23 “el ‘pelado’ se siente incómodo dentro de cualquier vestido, hábito o fórmula . . . rompe toda especie de tiranía; desea vivir a sus anchas.” BACK

-

24 “[las] convenciones vigentes”; “el explotador, el conservador, el hombre con fuero y privilegios.” BACK

-

25 “suele emplearse como sinonimia de ‘pelado,’ para calificar, conminar, contener, reprochar e injuriar al atrevido que se iguala.” BACK

-

26 “‘pelado’ quien no se sirve de alambicamiento en palabras y conducta; ‘pelado’ . . . [es] el que no condiciona y reprime todo movimiento espontáneo, adverso al prejuicio de “buena educación,” y hasta el que, tenido en nivel inferior, trata de igualarse . . .” BACK

-

27 “replica al amo”; “que da la razón a los indios y a los pobres”; “dice crudamente la verdad y señala corruptelas.” BACK

-

28 “‘pelado’ quien no se sirve de alambicamiento en palabras y conducta . . .” BACK

-

29 Anderson summarizes an anecdotal account (84) in which President Ruiz Cortines installed Yáñez as governor of Jalisco largely based on the merits of how he could use language: being a “man of the pueblo” but also demonstrating facility with “términos de gente culta” (97). BACK

-

30 “[gobernar] no deja de ser, en realidad, labor de novelista, de un novelista que conjuga la realidad con la imaginación.” BACK

-

31 Anderson highlights a 1958 profile of Yañez in México en la Cultura in which Yáñez, unlike other politicians of the era, “transcurre por la ciudad en el camión o en el tranvía, que participa en los problemas de los humildes y comparte sus gustos” (in Anderson, "Agustín Yáñez’s Total Mexico" 96). BACK

-

32 “empleará los recursos que juzga adecuados: palabras llanas, expresiones directas, lugares comunes . . . . [un] sentido artístico, aunque escape a la medida que los retóricos prescriben.” BACK

-

33 “De la realidad actual, miserable, aspira el Pensador a una realidas

posible, dichosa”; “la servidumbre en todos los órdenes” to “[el] regimen de plena libertad económica, política, espiritual.” BACK -

34 “[puede] hacer pensar a las gentes que, tal vez, menos contaban”; “[Así Lizardi postula] el porvenir de México, entendido y querido como una renovación incesante, progresiva.” BACK

-

35 While Harris does not mention it, “permanent revolution” is a key term for Trotsky. My thanks to Emilio Sauri for pointing this out. BACK

-

36 Ignacio Sánchez-Prado, “The Limitations of the Sensible: Reading Rancière in Mexico’s Failed Transition,” Parallax 20, no. 4 (2014), 381. BACK

-

37 “[esto] explicaría el estilo del Pensador”; “las plazas en que los desocupados toman sol e imploran los mendigos”; “la plétora de imágenes y adornos en retablos y fachadas barrocos,. . . . en lo que la actitud de cientos y cientos de figuras dicen otras tantas lecciones de ejemplaridad.” BACK

-

38 Agustín Yáñez, Ojerosa y pintada: la vida en la Ciudad de México, Obras escogidas, (Mexico City: Aguilar, 1968), 977-1136. BACK

-

39 “Hablan de la canalla. Esos infelices, muertos de hambre, que no saben distinguir con quién tratan. Se han hecho imposibles. Criados y porteros. Hasta los simples mandaderos. Igualados. . . . La grosería como norma. Lindezas de la democracia.” BACK

-

40 “no ha sido mala voluntad ni desprecio si no he podido servir a los pobres.” BACK

-

41 “está primero el número uno, ahora yo, y después el dos.” BACK

-

42 “Revolucionario inmaculado”; “energico, pero justiciero. Sabía reconocer sus errores. Alternaba como igual con sus subordinados . . .” BACK

-

43 “en su lucha sin descanso; le demostró lo que puede la constancia y la buena fe de un peón rudo, antecedente que no querían perdonarle los capitalinos presuntuosos . . . él sí llegará, como el general.” BACK

-

44 For an exploration of these questions in the context of contemporary photography, see Walter Benn Michaels, The Beauty of a Social Problem: Photography, Autonomy, Economy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). BACK

-

46 For an exploration of a similar dynamic in contemporary Mexico, see Hatfield, Limits of Identity 108-09. BACK

-

47 Stephen Buttes, “The Failure of Consuelo’s Design: Carlos Fuentes and Trompe L’Oeil Modernity,” Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos, 41, no. 2 (2017): 437-64. See also Stephen Buttes, “Para una literatura chorra: el realismo villero de Bruno Morales,” in Pobreza y precariedad en el imaginario latinoamericano del siglo XXI, 387-414. BACK

-

48 Bolívar Echeverría, La modernidad de lo barroco (Mexico City: Ediciones Era, 2013), Kindle Edition. BACK

-

49 See also, Ignacio M. Sánchez-Prado, “Reading Benjamin in Mexico: The Tasks of Latin American Philosophy,” Discourse 32, no. 1 (2010) 37-65 and Oswaldo Estrada, “Ráfagas de crueldad y pobreza en la literatura mexicana de la violencia,” in Pobreza y precariedad en el imaginario latinoamericano del siglo XXI, 139-56. BACK

-

50 “mestizaje cultural ‘salvaje’, no planeado sino forzado por las circunstancias”; “el resultado de una estrategia espontánea de supervivencia”; “el cumplimiento de un programa utópico . . .”; “procesos inacabados e inacabables de mestizaje cultural.” BACK

-

51 See Buttes, “Consuelo’s Design.” The aesthetic problem of the “Baroque mode,” I note, is what Carlos Fuentes was addressing in his writing during the 1950s and 1960s. Rather than engage in reader-addressing disruptions of “decorum,” I argue that what Fuentes developed instead is what Michael Fried has called an antitheatrical artwork, particularly in the vein of what the art historian calls its “pastoral conception:” the fiction that the beholder has entered the fictional space of the artwork and engages it as if removed from beholding it. In my reading, Fuentes achieves this through his famous use of the second person in Aura. The key here is that Fuentes recognizes that the politico-aesthetic model of the Baroque that has been central to Mexico’s history is a problem that “must be solved rather than evaded” (“Consuelo’s” 458) by insisting on the normativity of meaning: the notion that the text means what it means regardless of how a reader sees it. In this sense, Fuentes’s use of the second person functions as something like the opposite of Williams’s account of the pelado. Williams—like Yáñez and Rancière—premises his politics on an open-ended system that requires one’s language or conduct to be seen as “improper” or an “ill use:” “you are” the lumpen threat, the pelado. Fuentes’s use of the second person is deployed in a closed, unified artwork that insists on the normativity of meaning, and that, unlike what Yáñez’s “Preliminary Study” might have us believe, there is a fundamental difference between Porfirio Díaz and Emiliano Zapata, regardless of whether they both were, at one time or another, “disparaged” as “ill using” pelados demanding equality in their given moments. BACK

-

53 "contenía un ataque a la esclavitud”; “en el mercado”; “desde ese momento, algo de martirio por la libertad; sufría por los ideales del pueblo.” BACK

-

54 Ignacio M. Sánchez-Prado, “Las reencarnaciones del centauro: El deslinde después de los estudios culturales,” in Alfonso Reyes y los estudios latinoamericanos, eds. Adela Pineda Franco and Ignacio M. Sánchez-Prado (Pittsburgh: Institutio Internacional de Literatura Iberoamericana), 63-88. “la política profunda de la obra de Reyes [es] una política que escapa de las praxis fáciles y de las falsas creencias del intelectual como redentor absoluto de las problemáticas de los marginados o como constructor de utopías inmediatas . . .” (“El deslinde” 70) BACK

-

56 “mantener la resistencia cultural de la literatura en su especificidad.” BACK