The “Go-For-Broke Game of History:” Modernist Photography in Mexico

When U.S. and Mexican artists and critics considered the question of the aesthetic autonomy of photography in the 1920s, they found themselves wrestling with the competing frameworks of a previous generation—namely, with the debate between pictorialism and a scientific conception of this technological apparatus—and the provocative modernist conception they devised, according to which objectivity and intentionality were inseparably linked, emerged out of the limitations of the existing paradigms. According to the scientific stance on photography, the machine embodies the promise to know the world independently of human subjectivity, beyond the fallibility of human observation. 1 Indeed, the camera renders subjectivity or intentionality irrelevant because, as Ian Jeffrey puts it, photography constitutes the “discovery of nature’s capacity to register its own images.” 2 The camera is thus the “pencil of nature,” to invoke the famous title of Henry Fox Talbot’s collection of photographs, but this indexicality categorically excludes artistic intention. Pictorialism, by contrast, rejected the claim that photography was not art. “To demonstrate that photography was an art” and challenge the reduction of photography to its “mechanical nature,” the pictorialists made “the photographic print” into “a hand-made object.” 3 By manually manipulating the print, the photographer would not simply record an objective scene but would also express an artistic intention or a subjective mood. In short, the issue amounted to seeing photography as either a way of knowing the world or as a mode of expression. In the Mexican context, this debate acquired further connotations insofar as the scientific position was linked with attempts to document the Revolution and to the extent that pictorialism became the aesthetic for capturing picturesque scenes. 4 Therefore, if photography asserted its aesthetic autonomy, it would seem to find itself committed to the project of manipulating the print and imitating painterly techniques to express a private subjectivity or a non-social view of the natural world.

The modernist photographers examined in this paper thus came to see that pictorialism established the artistic character of photography at the expense of the autonomy of the medium and of its social meaning. Desperately striving to secure photography’s place alongside the other arts, pictorialism betrayed the specific potential of the camera. As a result, one often finds modernists paradoxically agreeing with the scientific and documentary view on the non-artistic nature of the medium. For instance, Marius De Zayas, the Mexican art critic and close friend of Alfred Stieglitz, asserts flatly that “Photography is not art" (130). 5 However, he continues, “photographs can be made into Art” 130). But, for the modernist, they will not be made into art by manually manipulating the negative. They can only become art if they embrace what Paul Strand calls photography’s “absolute unqualified objectivity.” 6 Insofar as “[t]he full potential power of every medium is dependent upon the purity of its use,” any “attempt at mixture” produces “dead things” (142). Categorically rejecting the conventions of pictorialist photography, Strand asserts that “hand work and manipulation [are] merely the expression of an impotent desire to paint” (142). Photography could produce artistic results not because it expresses the artist’s subjective mood but because it was, to use the various terms of the day, “honest,” “straight,” and “objective.”

The notion of medium specificity plays a crucial role in the familiar story about the development of modernist photography. However, I would suggest that this story deflates the significance of the conception of objectivity at work in modernist photography because it reduces it to a matter of distinguishing photography from other artistic media. Modernist photography insists not only on the autonomy of the medium but also on its aesthetic autonomy. At the same time, it embraces the scientific conception of photography as the medium uniquely suited to revealing aspects of the world that the human eye cannot or does not normally see. To reconcile these apparently incompatible positions and take modernist photography seriously, we must clarify the conception of objectivity in the modernist project. Objectivity, for the modernists, does not amount to correspondence with an independent object, a correspondence that could be attained by abstracting from subjectivity, as, for instance, in the camera’s mechanical reproduction of what lies in front of the lens. The modernists acknowledge the indexicality of the camera, but they also suspend this indexicality by composing the picture to express the truth of the object, a truth that cannot be reduced to immediate appearances. In other words, the modernists attempt to defeat what we conventionally regard as “photographic truth” in order to assert the truth of mediation. Accordingly, the modernists reconceive objectivity as inseparable from intentionality. Contrary to the presumption that intentionality exists “in the mind,” modernist photography insists that intentionality exists only when it is objective, when it assumes a material realization to which it, nonetheless, cannot be reduced. And if intentionality must be objective, it cannot be conceived as merely subjective or private; it is necessarily public, and thus, shareable with others. The autonomy of modernist photography, I submit, amounts to this inseparability of objectivity and intentionality. 7 Modernist photography neither mechanically indexes the world nor projects a subjective meaning distinct from the object. It makes available a shared world of meaning that cannot be reduced to either immediate experience or brute material existence.

This paper will present an account of this objectivity-as-autonomy by examining how it was developed by various photographers in Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s: Edward Weston, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and Paul Strand. As Horacio Fernández and Salvador Albiñana have proposed, the moment of modernist photography in Mexico can be delimited by the publication of two works: Hugo Brehme’s Das Malerische Mexiko (Picturesque Mexico, 1923) and Anita Brenner’s The Wind that Swept Mexico (1940). 8 Brehme’s collection of photographs, which was a commercial success in Germany and Mexico, effectively identified the pictorialist aesthetic with the picturesque, with Mexico’s striking natural and cultural landscape. On the other side of the modernist moment, Brenner’s book made photography significant for its ability to document the turbulent history of the Mexican Revolution. This periodization helpfully brings to light how modernist photographers in Mexico not only rejected the pictorialist manipulation of the medium and its reduction to a document; they also found themselves refusing local color and grand historical events. 9 The photograph would have to be able to grip the viewer on the basis of its internal criteria, not because it registered remarkable content, like a volcano or revolutionary peasants. At the same time, everything would seem to be stacked against the possibility that photography could count as art, as more than an indexical document. Without pre-existing institutional supports that validate a work as art and working in a medium typically seen as merely mechanical, the modernists had to find ways to make their photographic works compel conviction as art on their own terms. In other words, the aesthetic autonomy of photography could not be assumed; it had to be asserted. 10 The modernists thus had to show how “external circumstances” could be “actively taken up by us in ways that are irreducibly normative” (Brown 30). Autonomy, in this sense, is not a matter of “metaphysical independence” (30). Rather, it is a question of “choosing that about which one has no choice” (36), of making a mechanical reproduction of reality into something meaningful. “Politics,” likewise, “requires choosing to intervene in the conditions that exist” (36), and herein lies the connection between the modernist commitment to autonomy and the critique of capitalism implicit in the Mexican Revolution. 11 Just as the revolution could only overthrow inert, stubborn social conditions by acting within those conditions, the modernists photographers aimed to make a natural mechanism meaningful precisely on the basis of its mechanical nature.

Before fleshing out this account of autonomy qua objectivity by turning to Álvarez Bravo, and Strand, we can briefly trace its outlines by looking at a decisive moment in Weston’s work in Mexico. When Weston arrived in Mexico in 1923 with Tina Modotti, he had already begun to move away from pictorialism, but he had not yet established the formal principles that would come to characterize his mature work. We might say that he was searching for inspiration when he went to Mexico, a vivid, exotic land that had not yet lost its authenticity to modern culture. But if the trip to Mexico put Weston in touch with nature, it did not lead him to take photographs of the picturesque local color because he had definitively abandoned the pictorialist aesthetic. “I might call my work in Mexico,” he once wrote, “a fight to avoid its natural picturesqueness.” 12 At the same time, Weston did not seek out the abstract forms of factories and smokestacks that had preoccupied him when visiting Ohio a year before the trip to Mexico. In a context overflowing with unique forms, but having proscribed for himself striking natural and industrial scenes, Weston made the surprising choice to spend hours exploring the aesthetic potential of a quotidian object: his toilet.

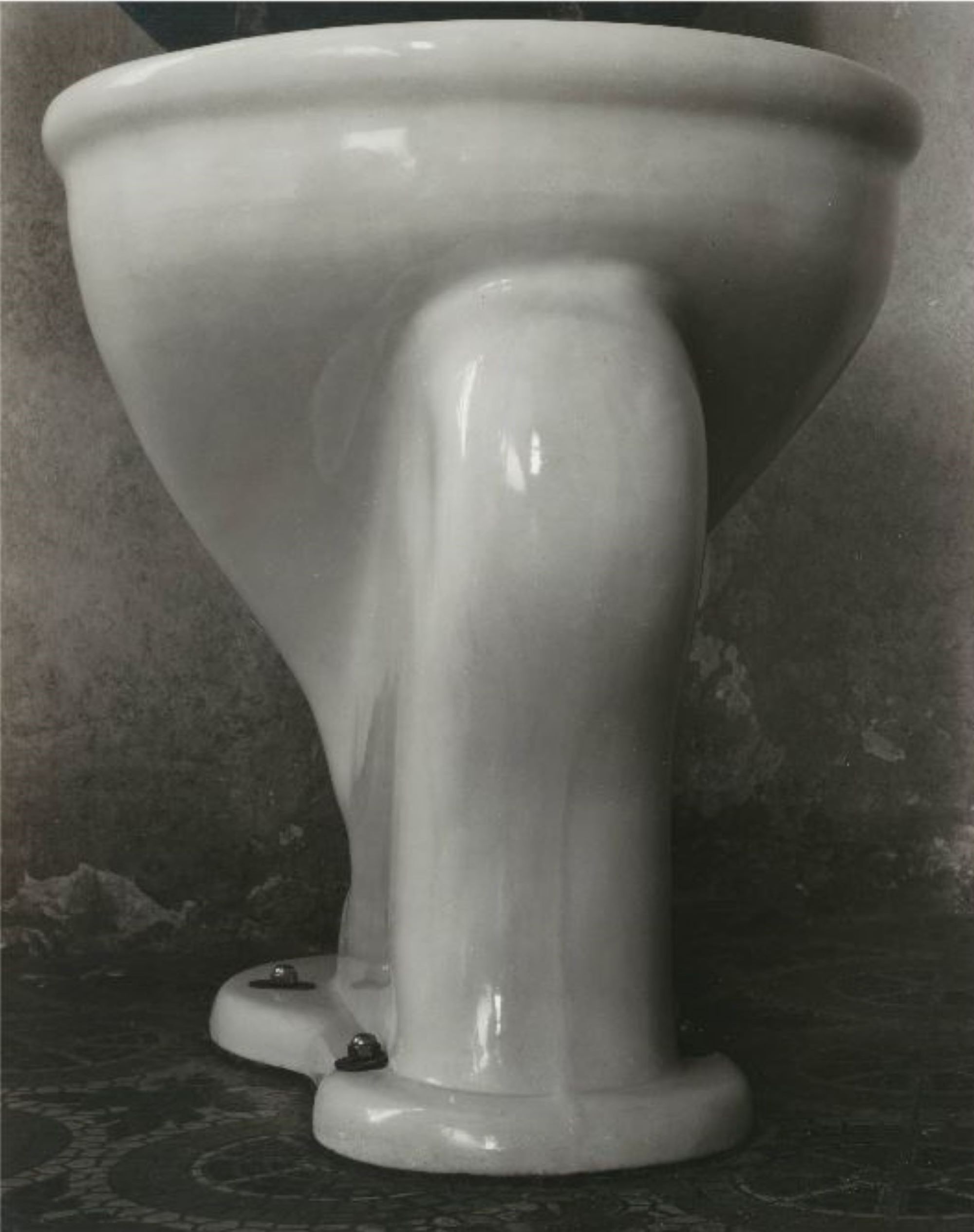

FIGURE 1. Edward Weston, “Excusado” (1925)

We might associate Weston’s “Excusado” with Duchamp’s Fountain and see the photograph as an ironic provocation concerning what counts as art. But Weston insists in his Daybooks that he was not “in a cynical mood,” but rather, that his “excitement was absolute aesthetic response to form” (Weston 132). “For long,” he continues, “I have considered photographing this useful and elegant accessory to modern hygienic life, but not until I actually contemplated its image on my ground glass did I realize the possibilities before me” (132). Indeed, the low angle brings out the aesthetic character of the toilet by making it appear unfamiliar. But we should also recognize that the perspective is not sufficient to generate this aesthetic response. After all, a plumber lying on the ground to fix the toilet would not see, as Weston claimed to see, a formal arrangement reminiscent of the Victory of Samothrace! It is the photograph itself, as something autonomous from our experience, that realizes the truth of the toilet, a truth that both subsists in the object and is inseparable from its representation. Accordingly, our interest in the photograph does not “drop through” 13 to the subject-matter, as it would when the meaning of a photograph lies in its documentary character rather than in the formal decisions made by the artist.

Indeed, “Excusado” exemplifies the striking formal principles that enabled Weston to denaturalize appearances in his subsequent studies of nautilus shells and peppers. The angle is unfamiliar, but the toilet remains recognizable. Weston eschewed abstraction, which someone like Strand had mastered a decade earlier, and rather than present a fragment of the toilet, he makes it fill the entire frame of the picture. Weston thus strips away everything extraneous in order to bring out the details of the shape, texture, and light of the thing itself.

This approach finds expression in the idea that “form follows function,” the phrase with which Weston’s entry on “Excusado” begins in the Daybooks. Weston admits that he does not know the origin of the phrase, but “the writer spoke well!” (132). The phrase resonates with Weston because it expresses the idea that form articulates the content of the thing itself, rather than being something externally imposed on it. The form of the toilet is functional, for Weston, not primarily because the toilet is something to be used, but rather, because the toilet embodies a unity of its shape and purpose, a unity to which photography should aspire. Accordingly, “Excusado” does not simply display the unity of its subject-matter; it must exhibit the unity of its own meaning and configuration. In achieving this unity in photography, the toilet becomes more than its immediate appearance. This “more,” however, should not be understood as something different than the toilet. As he explains to Ansel Adams in a letter concerning his photographs of peppers, Weston writes, “I did not mean ‘different’ than a pepper, but a pepper plus, —seeing it more definitely than does the casual observer, presenting it so that the importance of form and texture is intensified.” 14 In this way, the “plus” brings to light the precise nature of the modernist objectivity implied in Weston’s refusal of pictorialism. It neither amounts to something that has been added to the subject-matter by the subject 15 nor does it consist in a pre-existing truth that the camera can record because it operates independently of human subjectivity. It is a toilet plus because, in line with the scientific conception, the photograph shows us the world in an aspect that cannot be reduced to ordinary perception. And yet, unlike the scientific conception, the plus cannot be defined by its independence from human activity and intentionality because it only appears through the photograph’s unity of form and content. This unity can be established only on the basis of the autonomy of the photograph, not by passively indexing apparent existence. In its autonomy, photographic objectivity thus becomes a matter of shared meaning, a meaning that cannot be private because it is available to anyone, a meaning that is neither determined by nor independent from material existence.

The sort of objectivity at stake here cannot be separated from the photographic medium, but it is far more than a matter of identifying what is specific to photography compared to painting and other media. To make explicit the broader significance of this objectivity as a critique of capitalism, we can draw on the remarkable ending of Siegfried Kracauer’s 1927 essay on photography. 16 In the majority of the essay, Kracauer elaborates a critique of photography as the mere reproduction of familiar appearances. With the “blizzard of photographs” that one finds, for instance, in illustrated magazines, “Never before has an age been so informed about itself, if being informed means having an image of objects that resembles them in a photographic sense.” 17 And yet, despite having at its disposal a vast inventory of photographic reproductions, this “period know[s] so little about itself” (58). Photography, according to Kracauer, may give us exhaustive information, but it does not give us truth because it “betrays an indifference toward what the things mean” (58). Kracauer thus suggests that photography has undergone a profound reversal under the conditions of capitalism. Whereas the scientific conception valued the camera for its indifference to the subject, photography has become indifferent to the object. We can have images of every corner of the globe, but to the extent that in its “warehousing of nature” (62) photography turns everything into a two-dimensional rectangle, the images lack life and meaning. It is thus only with “modern photography” that “the foundation of nature devoid of meaning” comes fully into existence (61). Photography turns every object into a dead thing, and the “barren self-presentation of spatial and temporal elements” in photography “belongs to a social order that regulates itself according to economic laws of nature” (61). In capitalism, photography, by turning every object into a dead thing, contributes to the experience of social institutions as independent conditions, despite the fact that those institutions only continue to exist insofar as we sustain them through our ongoing activities. In other words, photography contributes to our alienation from ourselves and the world.

But Kracauer surprisingly suggests at the end of the essay that photography’s capacity for alienation could break the spell of alienation under capitalism. Insofar as photography reproduces the familiar world, “consciousness” remains “caught up in nature” and “unable to see its own material base” (61). But modernist photography takes up the “task” of “disclos[ing] this unexamined foundation of nature” because it incorporates “all spatial configurations … into the central archive in unusual combinations that distance them from human proximity” (61-62). 18 Whereas photography typically confirms the appearance of the world as something familiar in its alienation, modernist photography precipitates “the confrontation of consciousness with nature,” with what appears beyond our control in its law-like character (62). This is what Kracauer calls the “go-for-broke game of history” (61). Having shattered familiar appearances, modernist photography negates the immediacy of the world, but it also confronts us with our own intentionality, with our own activity in constituting that world, and it may even “awaken an inkling of the right order of the inventory of nature,” of how things ought to be (62, my emphasis). The modernists in Mexico, I will argue, make this risky wager on the idea that the autonomy of photography lies in the inseparability of objectivity and intentionality. In a variety of ways, they, unlike the pictorialists, acknowledge the mechanical character of the photographic medium, but they also suspend the mere indexicality of the camera by composing the pictures in such a way that they express shared meaning.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s Objective Irony

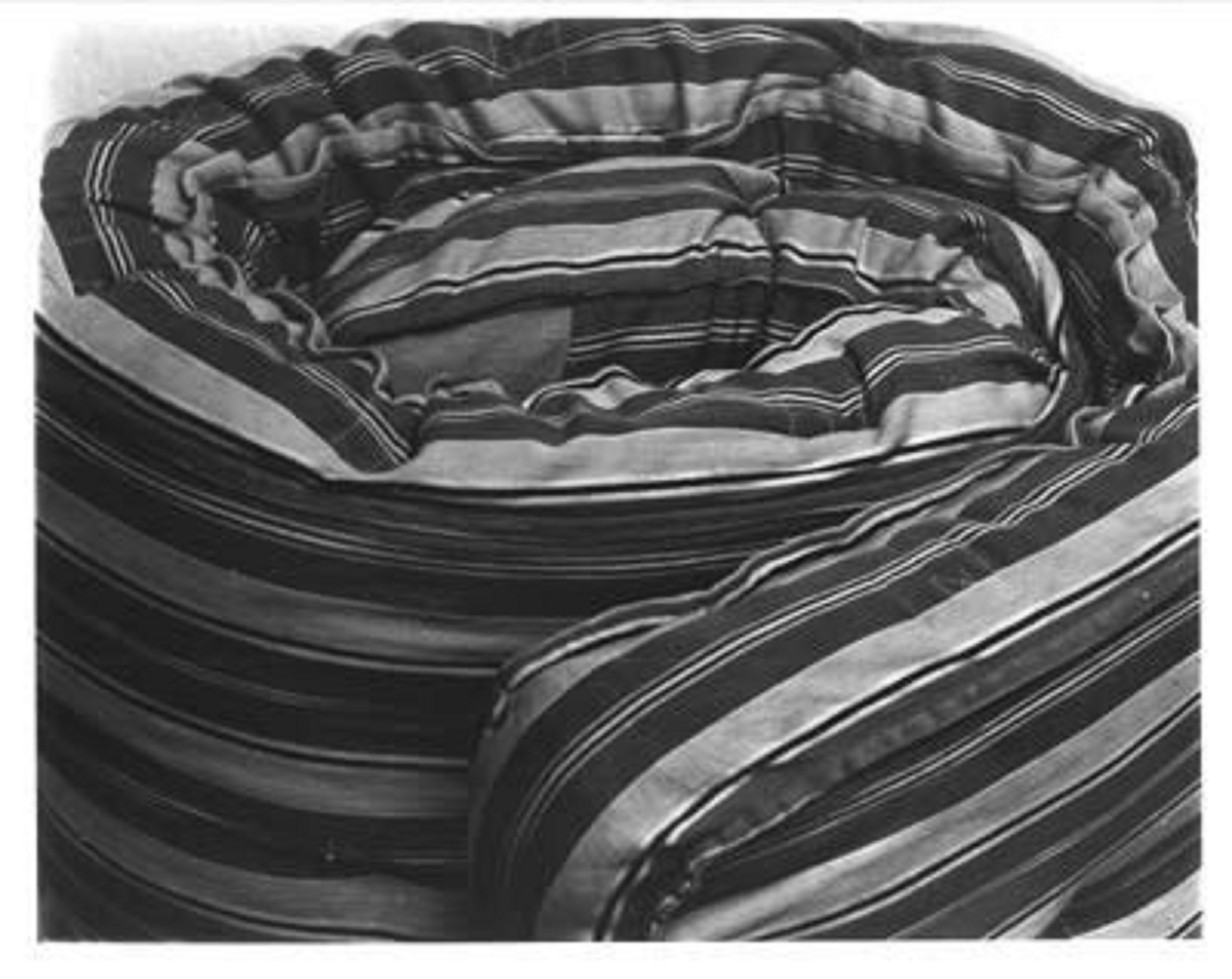

As I discussed above, the moment of modernist photography in Mexico should be understood not only, as in modernist photography more generally, as a rejection of the subjective manipulations characteristic of pictorialism and of the reduction of the medium to a document, but also in terms of the refusal of the picturesque and grand historical events. After Edward Weston and Tina Modotti established the foundations for this modernist direction in photography, it would be Manuel Álvarez Bravo (1902-2002) who most fully developed the tendency in Mexico. His 1927 photo “Colchón” (Mattress) provides an illuminating indication of both his debt to Weston’s “honest” photography and the irony for which he would become known. “Colchón,” like “Excusado,” closely frames an ordinary object, presenting it to the viewer in an unfamiliar but recognizable way. The goal, in other words, is not abstraction, but rather to draw attention to the texture of the mattress, a texture that has been enhanced by rolling it up. But “Colchón” also moves away from Weston’s formal principles through its ironic treatment of a national symbol. As John Marz notes, Álvarez Bravo “photographed a modern mattress, but with the twist that its bands of shading make it look like the well-known Saltillo serapes.” 19 The photograph thus evokes the artisanal product of a specific region even though the actual subject-matter is a mass-produced commodity. Whereas the picturesque simply does not appear in Weston’s “Excusado,” it undergoes a subtle inversion in Álvarez Bravo’s photography. “In order to say ‘not picturesque,’” according to Mraz, “Álvarez Bravo had to display the exotic and then cut back against the expectations awakened by its folklore elements, thereby taking the image in the opposite direction to critique it” (87). This sort of dynamic has led critics to portray Álvarez Bravo as an eminently ironic photographer. He often references a national symbol, but the actual subject-matter may be something far more mundane. Or he takes an ordinary object and discovers in it an unordinary meaning. Although critics rightly identify a pervasive ironic dimension in Álvarez Bravo’s photographs, we lose the significance of this irony if we fail to relate it to the objectivity of the medium. Normally, we understand irony as the subjective negation of literal meaning—i.e., I say X, but I mean not-X. But what makes Álvarez Bravo’s photographs ironic is not a distinct private meaning that could somehow be independent of what is present in the image. His ironic meaning is intentional, meaning that it can be distinguished, but not separated, from the objective expression. Acknowledging the specificity of the medium, Álvarez Bravo makes explicit the objective irony implicit in a scene, the reversals in meaning and shifts in point of view that are essential aspects of social life in Mexico.

FIGURE 2. Manuel Álvarez Bravo, “Colchón” (1927)

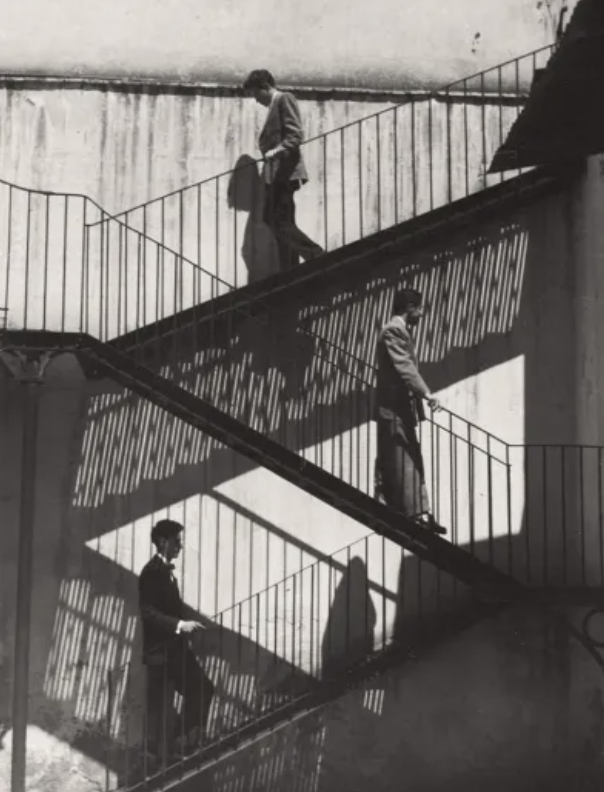

FIGURE 3. Manuel Álvarez Bravo, “La Tolteca” (1931)

The photograph “La Tolteca,” like “Colchón,” inverts apparent meaning to draw out the ironic truth of industrialization projects in Mexico. Before entering into a more detailed interpretation of the photograph, however, I should explain the peculiar occasion for which Álvarez Bravo produced this work. In 1932, this photograph won an art contest sponsored by the Tolteca 20 Cement Company to celebrate the recent construction on a modern factory in Mixcoac. Álvarez Bravo took the picture at the factory, and we see in the image a massive heap of limestone that could be used, for instance, to make the cement wall rising out of the raw material. When explaining the selection of Álvarez Bravo’s photograph as the winner of the competition, Federico Sánchez Fogarty, 21 the publicist for Tolteca Cement Co., claimed that the pile of limestone evokes indigenous pyramids in Mexico. The photograph thus suggests, according to Sánchez Fogarty, a continuity and transformation of the indigenous past into a modern future. Along these lines, we might compare Álvarez Bravo’s photograph to the work of the Mexican muralists. Both share, it would seem, a project of synthesizing industrial technology and indigenous symbols to construct a narrative of national identity.

The interpretation offered by Sánchez Fogarty seems plausible, but it fails to grasp the irony of the photograph. That is, it rightly identifies the apparent meaning, but it overlooks the crucial inversion of that meaning. This irony comes into view more clearly when we take into consideration the original title for the photograph: “Tríptico Cemento 2.” We might take the original title to mean that Álvarez Bravo intended to make the “La Tolteca” the center image of a triptych, but it seems more likely, given his way of naming other works, that the photo was to stand alone. By gesturing to missing images, the photograph would insist on absence. It would, in other words, insist on its irony, that its true meaning lies elsewhere, in the negation of what is immediately present. 22

The content of this ironic inversion, I would argue, becomes explicit when we recognize how Álvarez Bravo responds to Edward Weston’s 1923 photograph of the Pirámide del Sol at Teotihuacán. Weston’s photograph uses chiaroscuro, one side of the pyramid bathed in light and another side shrouded in darkness, to highlight dramatically how it was constructed. Through the details captured by a straight photograph, we see not only the pyramid as a whole but also the discrete stones held together by mortar. That is, the stones in Weston’s photograph retain their integrity and add up to a whole that is more than its parts. In Álvarez Bravo’s photograph, by contrast, these stones become the raw material that will need to be heated, pulverized, mixed and poured to construct the cement wall. Herein lies the ironic inversion of “La Tolteca.” Rather than present the industrial production of cement as the culmination of an impressive history of construction in Mexico, Álvarez Bravo suggests that industrialization depends on the ruination of the indigenous past. Rather than synthesize modern technology and indigenous beliefs, he gives us a visual expression of their opposition. The photograph thus casts doubt on the promises made by the post-Revolution Mexican state to simultaneously modernize the country and respect indigenous rights.

Insofar as “La Tolteca” makes a claim about the nature of industrialization projects in Mexico, the irony of the photograph cannot be understood as a private or idiosyncratic meaning imposed on the scene by the artist. Insofar as the true meaning of the photograph is a matter of intentionality, it must be present, but it cannot be merely present. The intentional meaning does not reside in the subjective mind of the photographer. Instead, it is absent in the sense that it is not immediately apparent. The irony—namely, the opposition between industrialization and the indigenous past—inheres in the objectivity of the photograph, in the pile of limestone, but this meaning only becomes intelligible as the negation of the claim about their compatibility.

Indeed, since both meanings are in the photograph itself, we also must revise the idea that the photograph is “really” about destruction of the indigenous past. As an objective photograph that is also ironic, “La Tolteca” embodies the contradictory way in which peripheral social formations stabilize the opposition of modernization and tradition. “La Tolteca” gives us a sense of the contradictory relationship whereby neither term overcomes the other, leaving the opposition intact while draining it of its dynamic character as a motor of change and emptying both terms of their meaning. In other words, “La Tolteca” does not suggest that industrialization has triumphed over indigenous tradition. It objectively records the ironic inversion whereby the post-Revolution Mexican state would fail to either

modernize the country or respect indigenous rights.

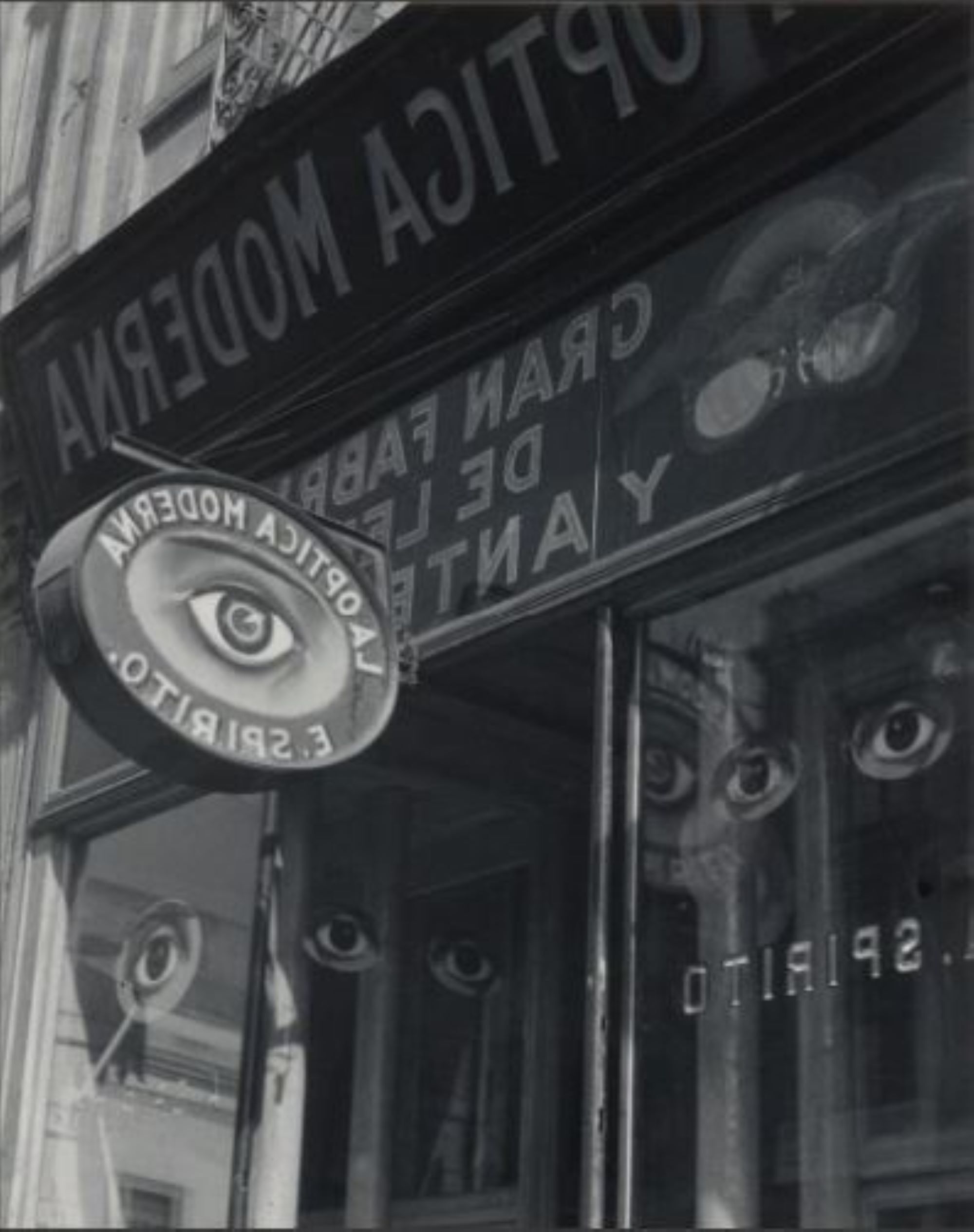

FIGURE 4. Manuel Álvarez Bravo, “Parábola óptica” (1931)

The implicit conception of photography in “La Tolteca” becomes fully explicit in “Parábola óptica” (1931), perhaps Álvarez Bravo’s most exemplary work. Insofar as the image features glasses and windows, it abounds in instances of transparency. This transparency seems to be linked to a modern mode of vision, “la óptica moderna,” alluding to the idea that we moderns see clearly, with opens eyes, what had previously been shrouded in religious mystifications. The camera would seem to embody the fulfilment of this “óptica moderna” because it records nature mechanically, independently of particular subjective beliefs, and can reveal what exceeds the limits of the human eye. In light of these aspects of the photograph, we might see the work as a “parable” about the objectivity of the camera.

But this interpretation would disavow the ironic dimension in the photograph whereby every instance of transparency undergoes an inversion. Álvarez Bravo flipped the negative, perhaps by accident, 23 thus reversing the text on the signs. The camera, the supreme expression of the transparent, “óptica moderna,” thus generates an image that ironically does not reproduce the world as it is in itself. Instead, it gives us a mirror image. This mirroring appears in another crucial inversion. “Parábola óptica” shows that windows do not simply allow us to see through the glass into an optical shop in Mexico City. Windows also reflect back to us what is happening on the street outside the shop. Álvarez Bravo gained an appreciation for this double aspect of shop windows from Eugène Atget. 24 Álvarez Bravo learned from Atget that, as Horacio Fernández puts it, “life is arrested” in shop windows and in photographs, making “photographic images of shop windows, always still-lifes, doubly latent, bringing them close to the courses of the uncanny, that awful sensation which affects well-known, familiar things as soon as they leave their customary context” (256). In Atget’s photographs, we often experience the uncanny because we see traces of a human figure in the reflections of shop windows, an ethereal presence caused not by manipulating the negative but simply as the result of a person passing by on the street during a slow exposure. Álvarez Bravo’s photograph alludes to this aspect of Atget’s work through the name of the owner of the shop, E. Spirito. While ghosts seem to haunt Atget’s images of Paris, Álvarez Bravo makes spirit legible on the shop windows of Mexico City. 25 With these inversions, Álvarez Bravo does not call into question the transparency of photography. He does not insist that it fails to live up to its own claims. He acknowledges the transparency of photography, but he also recognizes that it does not provide certain meaning or non-inferential knowledge of the world. Instead, the transparency of photography accommodates uncertainty and ambivalence.

To the extent that it grasps both objectivity and inversions, photography appears for Álvarez Bravo as the medium best suited to expressing social meaning in the Mexican context. Some critics, including Elena Poniatowska, 26 do not consider Álvarez Bravo to be an explicitly social or political photographer. If social issues appear in his work, he would seem to negate them, turning them into ironic vehicles for an idiosyncratic, personal meaning. But we can make intelligible the social significance of Álvarez Bravo’s photographs when we recognize the objective character of the irony. The objectivity here lies in a social situation where norms are systematically contradicted by material reality, but these norms are avowed nonetheless, in a social situation where ideas come to justify realities that would appear contrary to those very ideas. 27 These sorts of reversals proliferated in post-Revolution Mexico. The State was confronted by the acute contradiction between its revolutionary rhetoric and the ongoing reality of brutal inequality, but the revelation of this unvarnished reality did not precipitate an existential crisis for the political order. Instead, the State effectively accommodated the glaring gap between what it said and what it did. Documentary photography could expose the harsh living conditions for urban workers and peasants, but this sort of denunciation might actually bolster state power, not undermine it. Álvarez Bravo shared with documentary photography an aversion to the subjective manipulation of the medium and an interest in ordinary moments of urban life, but his photographs never claim to present a straight-forward meaning based on factual recording, as if a scene could be interpreted in only one way. The point of Álvarez Bravo’s irony is not to show how reality (say, the reality of poverty) contradicts ideas (say, the rhetoric of the post-Revolution Mexican State). Rather, Álvarez Bravo’s objective irony shows how the reality of Mexican society—understood as simultaneously material and ideal—systematically contradicts itself, making itself unstable and somehow sustaining itself through that instability. In short, by showing how a straight photograph can, in its very objectivity, accommodate incompatible valences, Álvarez Bravo formulates a mode of seeing that makes intelligible the contradictions of post-Revolution social life.

Paul Strand’s Natural-Social History of Mexico

Paul Strand, of all the modernist photographers, exhibits the most explicit commitment to objectivity. But, as I will argue in this section, the objectivity at work in his photographs undergoes an important development during his time in Mexico. Strand travelled to Mexico in 1932 on the invitation of the composer Carlos Chávez, who at the time was also the Director of Fine Arts for the Secretary of Public Education. Over the next two years, Strand would direct the film Redes (The Wage) and take over a hundred photographs, twenty of which he selected for a portfolio published in 1940. As for Weston, the stay in Mexico marked a turning point in Strand’s personal life and aesthetic vision. 28 By crossing the border, he effectively ended his relationship not only with his wife, Rebecca, but also with Alfred Stieglitz, his most important artistic mentor. Under the influence of Stieglitz, Strand had formulated the crucial notion that photography is a medium defined by “absolute unqualified objectivity.” At this time, he mastered abstract compositions and pioneered candid street photography. But by the mid-1920s, he had started to move progressively away from formalism and the city itself. He headed west, eventually settling in New Mexico. Along the way, he developed an eye for natural elements. But he never became a landscape photographer per se. He always maintained that “Things become interesting as soon as the human element enters in.” In Mexico, the “human element” partially indicated a turn to radical left-wing politics. The film Redes, for instance, depicts fishermen who organize to protest the meager remuneration given to them by the local businessman. The “human element” in Photographs of Mexico, by contrast, does not take the form of explicit political organization. Rather than engage in overt denunciation, Photographs of Mexico articulates a project that Strand would pursue throughout the rest of his life—namely, a social history through photography. This sort of social history would have to go beyond the mechanical reproduction of immediate appearances, without leaving appearances behind, to indicate the causes or context for the subject of the photograph. 29 As a result, objectivity here will not simply refer to the camera’s ability to index a given reality. During his Mexican moment, Strand will conceive of objectivity as a matter of our intentionality and sociality, our being in a world we share, and photography will have to objectify and alienate this sociality in order for it to be recovered.

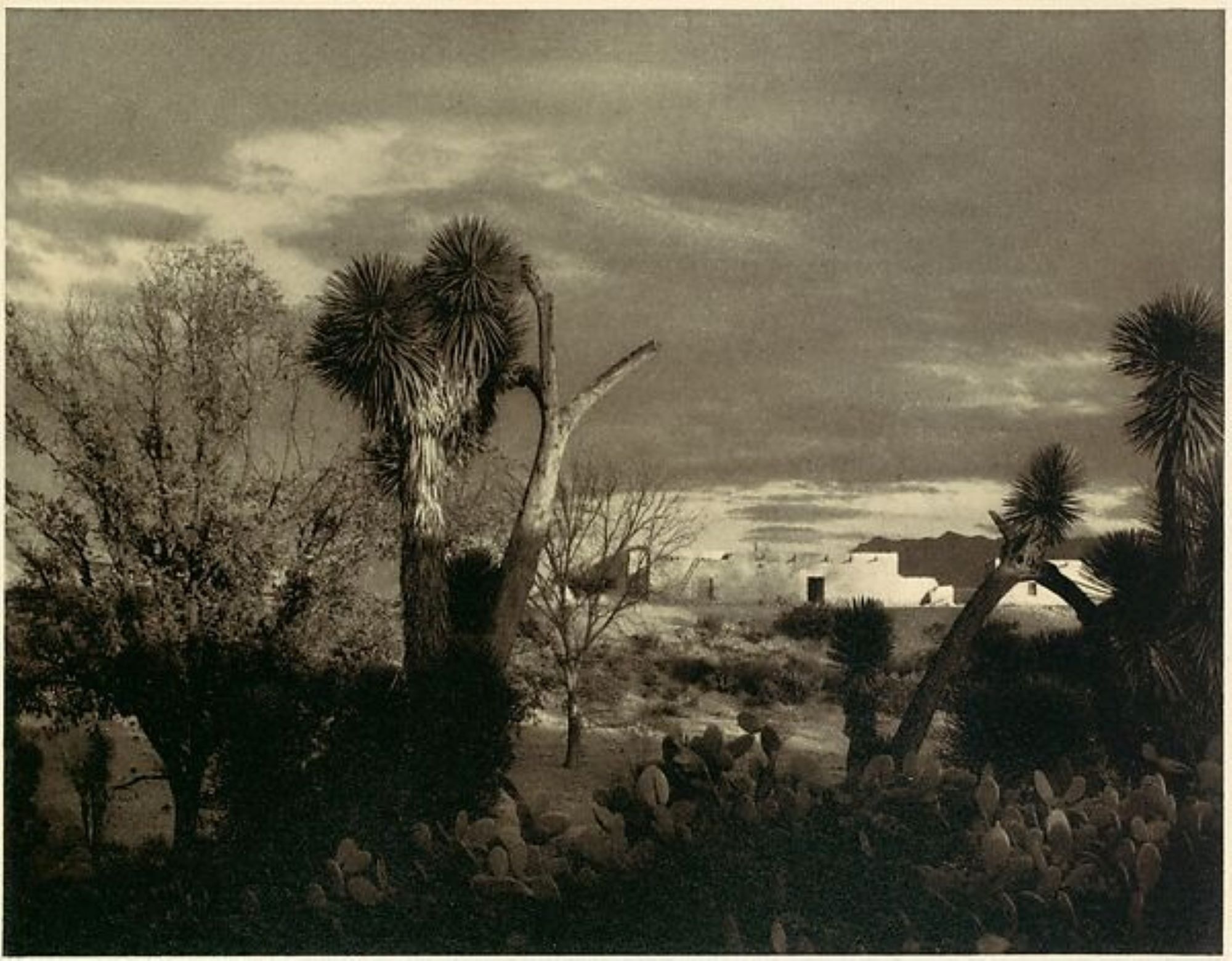

FIGURE 5. Paul Strand, “Near Saltillo” (1932)

I mentioned above that Strand increasingly focused on nature in the late-1920s as he moved away from experiments in abstraction. In light of this turn, it would perhaps not be surprising that one of his first photographs in Mexico, and the first in the collection, was a landscape: “Near Saltillo.” The natural beauty of Mexico would have presumably spoken to what many critics see as his romanticism, an impulse that remained dormant during the formalist, modernist phase. After a decade immersed in the industrial metropolis, perhaps Strand yearned to capture a cultural and natural Mexican identity that had not yet been corrupted by modernity. And yet, if “Near Saltillo” resembles picturesque photography insofar as it includes architecture and flora specific to that region (e.g., the prickly pear cactus, the adobe house), the composition of the picture does not present these elements as instances of local color, as recognizable examples of “Mexicanness.” Strand places the adobe house at the focal point of the picture, but the photograph does not reveal striking architectural details of the building. The stark contrast of light and shadow effectively reduces the house to bare white walls and a black doorway. The prickly pear cactus, likewise, figures prominently, but the shadow cast on the cactus by the clouds means that we cannot recognize the intricate texture of the plant, as we might in a Weston picture. Moreover, the cactus appears to constitute a thorny fence that prevent us from approaching the house. 30 Rather than give us a recognizable image of Mexico that one could hang on the wall, the picture simultaneously draws us in and keeps us at a distance. Katherine Ware has rightly argued that the first two pictures of Photographs of Mexico “provide a context for the human figures that inhabit the portfolio” (115). But this context does not make the human figures fully familiar; it does not construe them as consistent with presuppositions of what constitutes “Mexicanness.” “[B]y emphasizing the stark, rugged aspects of their built and natural environment” (115), Strand also alienates the natural-cultural setting, presenting it as something that will not admit us.

“Near Saltillo” thus suggests that Strand recognized that landscape photography could not recover the nature missing from his earlier work. A decidedly anti-romantic landscape, “Near Saltillo” acknowledges that this genre has always been premised on the alienation from nature. The art historian Christopher Wood, in a study of the first landscape painter, Albrecht Aldorfer, argues that landscape “was itself a symptom of loss, a cultural form that emerged only after humanity’s primal relationship with nature had been disrupted by urbanism, commerce and technology. For when mankind still ‘belonged’ to nature in a simple way, nobody needed to paint a landscape.” 31 Landscape, in other words, registers a world-historical transformation in which nature ceases to be the living background for human activities and becomes an independent, mechanical system governed by laws. A landscape painting apparently brings us closer to nature, but only in the form of a dead thing hanging on the wall. Photography, we might say, represents the culmination of this alienation insofar as turns everything, not merely natural settings, into a two-dimensional rectangle 32 and arbitrarily collects these images in what Kracauer calls “the general inventory” (61). In “Near Saltillo” Strand suspends the tendency of photography to indifferently reproduce objective reality not by making the landscape familiar, by making it conform to our expectations of what constitutes a Mexican landscape. Instead, he asserts the objectivity of the photography, its independence from the viewer, and brings us into the picture, thereby showing us that what is ours has somehow become not our own. Rather than falsely overcome our alienation from nature by giving us a pleasing image displaying the beauty of Mexico, “Near Saltillo” sustains the alienation from nature in such a way that we can see it and take a stand on it, can adopt an intentional attitude towards it.

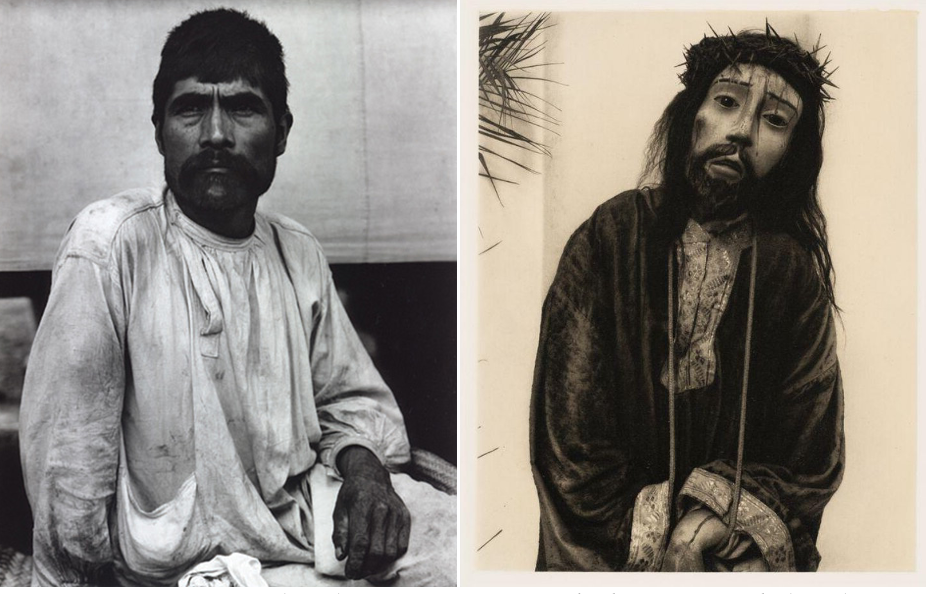

FIGURE 6 and FIGURE 7. "Man, Tenancingo, Mexico" (1933) [left] "Cristo with Thorns, Huexotla" (1932) [right]

When Strand turns to human subjects in Photographs of Mexico, alienation becomes more explicitly a matter of self-alienation. In these photographs, he often returned to the technique of using a trick lens to take candid pictures—that is, photographs of people who did not know they were being photographed, who were not posing for the camera. These photographs invade the subject’s privacy, but Strand insisted on the “seriousness” of this work, believing that he “was attempting to give something to the world and not exploit anyone in the process.” 33 Because these subjects are not conscious of being photographed, they appear as they could not see themselves, for instance, in a mirror. By alienating the subject from their self-image, the picture would be objectively true to the subject, not to how the subject wanted to appear. We might say that Strand’s candid portraits extend the scientific conception of photography from nature to people. Just as a photograph can reveal aspects of the world in itself, Strand’s candid pictures show people independent of their self-observation. But it is crucial to note that Strand’s subjects inhabit public, social spaces. They do not know they are being photographed, but they know that they share a space with others, including a photographer. They are neither for-the-photographer nor for-themselves. Instead, the photographs capture the subject as it is for-others. As a result, the alienation of the subjects in Strand’s candid photographs—their alienation from themselves—appears inseparable from their sociality.

The candid portraits in Photographs of Mexico stand out because Strand places these images alongside photographs of religious sculptures. On the basis of Strand’s compositional choices and the realistic nature of the sculptures, the viewer should sense a form of identity between, for instance, "Man, Tenancingo, Mexico" and "Cristo with Thorns, Huexotla." We thus see the remarkably lifelike sculpture of Christ as the work of the Mexican people who appear in Strand’s portfolio. Strand often found that photographs of ordinary objects and modest architecture told a more compelling social history than portraits could, and, indeed, the sophisticated sculpture suggests that these people cannot be reduced to conditions of poverty. The juxtaposition of images thus “ascribes,” in Katherine Ware’s words, “a Christ-like nobility, dignity, and humility to the man’s struggles” (118). While Ware rightly identifies the dignity that follows from inserting religious sculptures into the series, I would add that the portfolio does not insist thereby on the dignity of poverty itself. Paradoxically, Strand dignifies the human subjects here by equating them with statues. And insofar as the statue lacks life and movement, it stands in for the way photography freezes the subject and turns it into a dead thing. The dignity of the subject follows from this alienation; it is not a given condition that the camera mechanically records. The dignity, in other words, is a matter of the autonomy of the photographic work, of the way that candid photography can capture a capacity for sociality. In the same paradoxical way that Strand makes dignity inseparable from the lifelessness of a statue, he also insists that the notion of dignity, of intrinsic value, depends on being-for-others, on the alienation of our immediate self-relation.

If this interpretation of Strand is right, it runs counter to the prevalent image of Strand as a romantic. After experimenting with abstraction, industrial aesthetics and the city, Strand largely dedicated himself to taking photographs of natural elements and village life, both in the United States and internationally. But this putative romanticism, the attempt to recover non-modern modes of life in Mexico, for instance, contrasts sharply with Strand’s characteristic coldness and indifference. Fred Zinnermann, co-director of Redes, once remarked that Strand “loved humanity in the abstract rather than in the specific.” 34 Strand’s candid portraits and the Photographs of Mexico embody this constitutive tension in his work between objectivity and passionate commitment. But rather than see this tension as untenable, we should grasp it as the key to Strand’s politics and aesthetic point of view. Along these lines, Blake Stimson argues that the “highest historic aim taken up by modern art and communism alike was to inhabit” what Marx called “loss of character” and Strand called the “love” of “a dead thing” (Stimson 24). Rather than attempt to “somehow step outside of alienation back into a religious or pseudo-religious holism,” Strand insisted on “owning up to being a cog in the machine, accepting that the effective and apperceptive conditions of modern life disaggregate the experience of social being from an organic whole into a mechanical experience of its parts,” and it is only in acknowledging that mechanical existence that we can “artificially refashion an even more synthetic social being and character from its lonely and disaggregated parts” (24). At the level of content, Strand’s Photographs of Mexico seem to ignore this disaggregated mechanical life in favor of religious sculptures and peasants. But I have tried to show that at the formal level of composition and techniques, Strand was preoccupied with this modernist project of constructing a coherent and dignified form of sociality on the basis of our loss of individual character. The photographs present sociality as something objective to both index its alienation under capitalism and to make it available to anyone, not tied to specific individuals.

Strand’s conception of the objective character of sociality becomes explicit while working in Mexico, and it clarifies what is at stake in his earlier thoughts on the absolute objectivity of photography. Strand’s Mexico moment, in other words, adds a social dimension to his earlier preoccupation with the relationship between the artist and the machine. In “Photography and the New God” (1922), Strand insists on the anachronistic character of art in a post-religious world. We have, he claims, created “a new Trinity: God the Machine, Materialistic Empiricism the Son, and Science the Holy Ghost,” and the “intuitive,” spiritual work of the artist has “no value in a fairly unscrupulous struggle for the possession of natural resources, for the exploitation of all materials, human and otherwise” (145). Towards the end of the essay, Strand warns that “the whole Trinity must be humanized lest it in turn dehumanize us” (151). Strand does not make this call for the humanization of science and the machine from the melancholic point of view of the traditional intuitive artist. Rather, he asserts that it is in photography that the artist can “establish his own spiritual control over a machine” (151). The photographer, for Strand, can only fulfill this purpose and exercise “spiritual control”—or what I have been calling intentionality—over the machine by acknowledging its “absolute unqualified objectivity,” not by lapsing into the religious temptation to manipulate the medium to make nature into a vehicle for the expression of subjective meaning. “Photography and the New God,” in other words, aligns objectivity with the machine in the confrontation between the artist and the new trinity, but in light of the Photographs of Mexico, we should recognize that modernist objectivity is a matter of our alienated sociality. The gamble of modernist photography lies not only in establishing spiritual control over a technological apparatus but also, and perhaps more importantly, in alienating our sociality such that it can be seen as something that we have both lost and not yet attained, such that our intentionality can be recognized as necessarily objective and shareable with others, not trapped within a self-contained private existence.

Tavid Mulder teaches global literature and literature of the Americas at Emerson College. He has published various articles on Latin American literature, global modernism and dialectical criticism in Mediations, A Contracorriente, Comparative Literature Studies, CLCWeb and Modernism/Modernity Print+. He is the author of Modernism in the Peripheral Metropolis: Form, Crisis and the City in Latin America (Palgrave, 2023).

Notes:

-

1 See, for instance, Blake Stimson and Robin Kelsey, “Introduction” in The Meaning of Photography (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008). BACK

-

2 Ian Jeffrey, Photography: A Concise History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 10. BACK

-

3 Miles Orvell, American Photography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 84, my emphasis. BACK

-

4 On these tendencies in Mexican photography in the early twentieth century, see John Mraz, Looking for Mexico: Modern Visual Culture and National Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 13-48 and Roberto Tejada, National Camera: Photography and Mexico’s Image Environment (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 19-54. BACK

-

5 Marius De Zayas, “Photography and Artistic Photography,” in Classical Essays on Photography, ed. Alan Trachtenberg (New Haven, CT: Leete’s Island Books, 1980), 130. BACK

-

6 Paul Strand, “Photography and the New God,” in Classical Essays on Photography, ed. Alan Trachtenberg (New Haven, CT: Leete’s Island Books, 1980), 141-2. BACK

-

7 To make explicit the philosophical framework here, I am invoking a phenomenological concept of intentionality. That is, intention is neither a thing contained in the mind nor a mental cause that exists prior to and independent of the action that realizes the intention. In the phenomenological tradition, intentionality means being aimed at or directed towards the world. Moreover, if every intentional attitude is directed towards the world, then intentionality must be social insofar as this world is a meaningful world. BACK

-

8 Horacio Fernández and Salvador Albiñana, “La óptica moderna” in Mexicana: fotografía moderna en México, 1923-1940, eds. Horacio Fernández and Salvador Albiñana (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 1998), 16. BACK

-

9 We could also add to this periodization by insisting that modernist photography not be simply identified with either a national-popular orientation or a cosmopolitan formalism. These “two avant-gardes,” as Ángel Rama called them in an influential essay, would seem to be embodied in Mexican muralism, on the one hand, and estridentismo, on the other hand. Whereas the former employed a public medium to communicate with the masses and construct a history of Mexico by synthesizing indigenous, colonial, and modern elements, the latter sought to break with tradition and inaugurate a radical modernity on the basis of industrial technology. Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, arguably the two founding figures of modernist photography in Mexico, took inspiration from the muralists and estridentismo, but their work could not be fundamentally defined by either tendency. Indeed, I would argue that the notion of the “two avant-gardes” in Latin America proves to be inadequate because it prioritizes criteria that are external to the work—such as material manifestations of modernity or a putative national identity that art should express—and these limitations stand out when we examine modernist photography in Mexico and its intense attention to internal criteria. See Ángel Rama, “Las dos vanguardias,” Maldoror 9 (1973): 58-64. BACK

-

10 Nicholas Brown, Autonomy: The Social Ontology of Art Under Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). Brown writes that “After postmodernism, autonomy cannot be assumed, even by works produced for a restricted field. It must instead be asserted” (22). In the case of modernist photography in Mexico, autonomy cannot be assumed because the standing of photography as art was still very much open to debate, not primarily because, as in Brown’s account, of the universal domination of the commodity-form. BACK

-

11 I say “implicit” to distinguish this critique of capitalism from the explicit appeal to socialism made by various leaders of the Mexican Revolution, both during the 1910s and its subsequent “institutionalization.” The Mexican state’s explicit critique of capitalism was little more than rhetoric. BACK

-

12 Edward Weston, The Daybooks of Edward Weston, ed. Nancy Newhall (New York: Aperture, 1981), 66. BACK

-

13 On “dropping through” and its opposite, revelatory photographs, see Dominic McIver Lopes, Four Arts of Photography: An Essay in Philosophy (Malden, MA: Wiley, 2016), 36-47. BACK

-

14 Ansel Adams, Mary Street Alinder, and Andrea Gray Stillman, Ansel Adams: Letters and Images, 1916-1984 (Boston: Little Brown, 1988), 48-49. BACK

-

15 This sort of approach lay behind Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents, a series of images of clouds that were supposed to be “equivalent” to emotional moods. For Weston, the Equivalents, despite being seen by many as a significant development in modernist photography, represented the culmination of the pictorialist betrayal of photographic objectivity. BACK

-

16 For an excellent discussion of Kracauer’s essay on photography, see Steve Giles, “Making Visible, Making Strange: Photography and Representation in Kracauer, Brecht and Benjamin,” New Formations 61 (2007), 64-75. BACK

-

17 Siegfried Kracauer, “Photography,” in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, trans.Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 58. BACK

-

18 Kracauer does not refer to “modernist” photography by name, but he alludes to how modernist experiments in photography, for instance, show “cities in aerial shots” (62). BACK

-

20 James Oles explains that the name “Tolteca,” in addition to referring to the civilization previously inhabiting the Valley of Mexico, signifies something like the idea of artistry. James Oles, “The Modern Photography and Cementos Tolteca: A Utopian Alliance,” in Mexicana: fotografía moderna en México, 1923-1940, eds. Horacio Fernández & Salvador Albiñana (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 1998), 274. BACK

-

21 Sánchez Fogarty was also a fervent supporter of functionalist architecture in Mexico. On Sánchez Fogarty and cement in Mexico, see Rubén Gallo, Mexican Modernity: The Avant-Garde and the Technological Revolution (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), chapter 4. BACK

-

22 With regards to what is missing, James Oles notes the “not-so-insignificant” absence of workers in the photograph (274). By excluding the workers, “[i]n Álvarez Bravo’s photograph, the transformation of raw materials into finished products is presented as effortless and inevitable, isolated from the problematic demands of unions and the restraints of labor laws.” Oles, “Modern Photography,” 274. BACK

-

23 Horacio Fernández suggests that the reversal “was probably a technical mistake . . . which Álvarez Bravo liked.” Horacio Fernández, “Manuel Álvarez Bravo,” in Mexicana: fotografía moderna en México, 1923-1940, eds. Horacio Fernández & Salvador Albiñana (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 1998), 258. BACK

-

24 Insisting on the encounter with Atget as a turning point, Horacio Fernández says, “[w]ith Manuel Álvarez Bravo there is a before and after having seen the work of Atget, which must have occurred in about 1930.” Fernández, “Álvarez Bravo,” 256. BACK

-

25 But, crucially, these ghosts and spirits are not other-worldly. In Álvarez Bravo’s hands, photography expresses a spiritual existence that must be materially embodied but cannot be reduced to its embodiment: in other words, social meaning. BACK

-

26 Poniatowska distinguishes Álvarez Bravo’s lyrical ambiguity from Modotti’s political romanticism. See Elena Poniatowska, “El retrato del viento: Manuel Álvarez Bravo” Bulletin of Spanish Studies 92, no. 7 (2015): 1051-1062. BACK

-

27 I owe a tremendous debt here to Roberto Schwarz’s discussion of the objective irony of Machado de Assis. In his remarkable analysis of The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, Schwarz writes that “the irony of the Memoirs is not limited to denouncing” the continued existence of slavery in liberal, late-nineteenth century Brazil. Rather, “the novel specializes in observing and conceiving sequences in which modern forms are twisted to serve the peculiar ensemble of local interests”—i.e., slavery. Roberto Schwarz, A Master on the Periphery of Capitalism, translated by John Gledson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 81. BACK

-

28 Katherine Ware writes that the Mexico “portfolio is both a prototype and an anomaly in Strand’s oeuvre, a transition piece deeply rooted in his early experimentation with formalism and the genres of portraiture and landscape, yet breaking new ground in combining these elements to create work that used fine art techniques to dignify and vivify the human condition while using the human condition to bring meaning and social relevance to the realm of art.” Katherine Ware, “Photographs of Mexico, 1940,” in Paul Strand: Essays on His Life and Work, ed. Maren Stange (New York: Aperture, 1990), 110. BACK

-

29 John Roberts helpfully describes this dynamic when he writes: “in a photograph there exists empirical evidence of the palpable truth of appearances (‘this looks like …’), but also evidence of the social determination of these appearances (‘this looks like … because of …’); and this evidence will thereby form the causal and interpretative basis for the discursive reconstruction of the image.” John Roberts, Photography and Its Violations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 1-2. BACK

-

30 Along these lines, we might compare “Near Saltillo” to Strand’s famous “White Fence” photograph from 1916. But the latter fully illuminates the fence and brings it close to the viewer whereas the former obscures the natural fence at the same time that it places it in the foreground. BACK

-

31 Christopher Wood, Albrecht Aldofer (London: Reaktion, 1993), 25. BACK

-

32 I am alluding here to a comment from Robert Smithson. In an interview, Smithson claims that “the earth after photography becomes more of a museum” because “photography squares everything. Every kind of random view is caught in a rectangular format” (188). For Smithson, this critique of photography justifies his site-specific art, whereas I would argue that modernism attempts to overcome “squaring everything” from within photography itself. See Robert Smithson, “Fragments of a Conversation,” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 188-91. BACK

-

33 Quoted in Mark Whalan, “The Majesty of the Moment: Sociality and Privacy in the Street Photography of Paul Strand,” American Art 25, no. 2 (2011): 45. Candid photographs and trick lenses already existed in the early twentieth century, but, as Mark Whalan helpfully reminds us, these sorts of photographs were often taken of attractive women for the purpose of selling postcards, for instance, and decoy lenses were marketed to private detectives. BACK

-

34 Quoted in Blake Stimson, “Photography and God,” Oxford Art Journal 38, no. 1 (2015): 21. BACK