“The Borders of the Frame:" Chicanx Feminism and the Problem of Representation

This essay studies the formally innovative and captivating works of Gloria Anzaldúa, Ana Castillo, and Alma Luz Villanueva to show how their texts published in the 1980s confront representational problems that Chicanx writers of the 1960s and 1970s had not addressed. Even though a coterminous development called postmodernism had begun to “problematize” the very concept of representation as it had been understood, the most well-known Chicanx writers of the previous decades had created works of literature that unproblematically claimed to speak for a Chicanx community. 1 During the 1960s and 1970s, a distinctly Chicanx literature was presented as able to consolidate a collective identity and ensure that this identity is institutionally recognized within the United States as part of its history. 2 For Chicanx feminists, however, the very term “Chicano” appeared too exclusionary, overtly gendered and nationalistic, and therefore not representative of their own experience. 3 As I will show in what follows, Chicanx feminists took seriously postmodernism’s challenge to the established academic discourses and institutional systems claiming to make knowledge available neutrally. They highlight the process of representation in their texts, presenting it as a vexing issue to be circumvented if it is not resolved.

Their texts thus thematically dramatize a search for the literary and artistic forms that could begin to convey their experiences and perspectives adequately and express the stories of women who have been perennially misrepresented when not silenced. The writers do not presume their ability to speak for others, yet they recognize the necessity to do so responsibly because no one else would. Their formal experimentation leads them to turn to innovative representational strategies, which include the use of personification (which imagines texts not as literary forms but as embodied persons) and performance (which invites the reader to engage in an open-ended experiential event). Stated formulaically, the writers considered here develop the fictive technologies that enable the conversion of the question of representation (how A can represent B) into the assertion of an identity (how A is B). And whereas the “Chicanx community” had been taken as a given during the 1960s and 1970s, the reader is more consciously invoked and invited to participate in the work of Chicanx feminists. Insofar as representation came to be seen as a problem, the observing, performing reader experiencing the text (for Anzaldúa and Villanueva, the text-made-flesh) became part of the proffered solution.

During the 40 years since these texts were published, literary critics, theorists, and historians have spoken of these artistic strategies as philosophical accomplishments that exposed the deficiencies of Chicano nationalism and misogyny and helped create alternative methodologies. 4 These solutions have been characterized as enabling a resistant, progressive way forward not only in debates about literature and art but also in debates about politics. 5 Elizabeth J. Ordóñez, for example, describes how Alma Luz Villanueva’s poetry “synthesizes sexuality (or the female body), spirituality, and the poetic text,” thereby undoing the Cartesian binary oppositions so prevalent in the western philosophical tradition. 6 Although the communication of “life’s experiences...requires language as a mediating vehicle,” argues Ordóñez, Villanueva’s writing refashions “mediation” into something like emanation: “form never becomes intrusive” because “Woman and word...become one.” 7 I too consider these texts to be immensely important, but I will show why they have not been as resistant as has been claimed.

If the metaphorical conversion of text to body prevents misrepresentation, it does so by foreclosing textual meaning. Insofar as authors imagine presenting personified textual bodies to their audiences, “readers” are not asked to read and attempt to understand so much as witness and experience the text-as-body’s identity. If I am witnessing a body and you are too, my experience will differ from yours depending on where I stand. I could describe to you my experience in relation to where I stood, what I saw, what I felt, everything about my subject position as a witness. And you could describe your experience based on your subject position. We would not disagree about our different experiences because agreement and disagreement would have been rendered beside the point. As Charles Hatfield cogently argues, “interpretive disagreements are converted into descriptions of the identitarian differences between readers” because one’s experience of a text is simply one’s own and will differ from everyone else’s. 8 The identity of the textual body is paramount, as is the identity of the experiencing spectator, while the interpretation of meaning is rendered irrelevant. What an author has to say appears to be less relevant than who she is and who she produces, and her texts do not demand understanding so much as recognition.

By neutralizing meaning through textual personification, these strategies foreclose the possibility of the debates necessary to figure out what solutions should be advanced. Chicanx writers unwittingly participated in the transition that took place during the 1980s that deemphasized structural, economic critique and instead advanced identity politics demanding recognition. Nancy Fraser argues that the 1980s witnessed the “broader cultural shift from the politics of equality to the politics of identity,” in which previous calls for the redistribution of resources that would benefit women were transformed into demands for the recognition of women’s difference. 9 Describing the shifts from state-managed capitalism to free-market capitalism that overvalued free trade, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Fraser highlight the multiple directions feminism could have taken, yet the approach that gained the most traction prioritized recognition over redistribution and thus advanced the goals of the economy’s beneficiaries while leaving the majority of women in need. 10 The “emphasis on getting women into positions of power and prestige,” writes Deborah L. Madsen, “has meant preserving the existing socio-economic system, and the result has been increased poverty of the majority of women.” 11 Although the beneficiaries of the economic hierarchy would be importantly more diverse because of its increased inclusion of women, the structure of that hierarchy would otherwise remain intact. As crucial as the call for recognition remains, it can risk deemphasizing the varying criticisms that women articulate about the existing social order, what political views they advance, and what disagreements will inevitably ensue concerning these views.

The Search for Form

In a letter included in Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa’s edited collection This Bridge Called My Back (1981), Anzaldúa describes how writing an essay felt “wooden, cold” because of the “esoteric bullshit and pseudo-intellectualizing that school brainwashed into my writing.” 12 “How to begin again,” she wonders, “How to approximate the intimacy and immediacy I want? What form?” She settles on a genre associated with intimacy among friends, “A letter, of course,” yet this letter also includes excerpts from her journal and quotations from poems written by women of color. Addressing the poets, she writes, “It’s not on paper that you create but in your innards, in the gut and out of living tissue—organic writing I call it. A poem works for me not when it says what I want it to say and not when it evokes what I want it to” (170). Anzaldúa’s search for the adequate “form” leads her to reject the imposition of extraneous mediation (she wants “immediacy”), so she turns to what Amy Hungerford has described as a familiar postwar tendency “to imagine the literary text as if it bore significant characteristics of persons.” 13 Her poems “work” when she imagines them as composed of her tissue. We see a similar search for form and a resulting turn to personification in Alma Luz Villanueva’s poems collected in Life Span (1985). The poem “The Labor of Buscando La Forma” (“The Labor of Looking for Form”) links the search for form to the labor of giving birth, while her poem “Communion” imagines “a life” “pregnant with words.” 14 As Suzanne Bost argues, this invocation of pregnancy is not meant to “reinforc[e] the sexist notion that motherhood is all defining for women and potentially conflat[e] the author with the persona in the poem” (3). Yet, the use of personification does indicate a desire for the transubstantiation of language that is able to transcend the limits of representation. In the poem “Communion,” the Catholic Eucharist— the “wafer / of living flesh” (1)— offers a symbol of the word becoming flesh. Poems thus imagined do not represent meaning so much as present themselves being.

This turn to personification appears to solve one epistemological problem by insisting on an ontological solution. Poems (like the Eucharist) do not represent; they are. This ontological solution, however, will inevitably return us to the epistemological problem. If the poet gives birth to the poem, it is not clear that the poem will remain expressive of the poet. After all, the New Critics W. K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley famously employ the metaphor of birth when describing a disconnect between a poem and its author. “The poem,” they write, “is not the author’s...it is detached from the author at birth.” 15 We are again confronted by the epistemological question of how one might represent one’s thoughts and the political question of how one can adequately speak for others. This is why, in Borderlands/La Frontera (1987), Anzaldúa also imagines her works as “acts encapsulated in time, ‘enacted’ every time they are spoken aloud or read silently.” They are “performances” and decidedly not “inert and ‘dead’ objects” (89). By inviting her readers into the performance, Anzaldúa can incorporate them into the identity of her poems. A recitation included in Borderlands exemplifies this dynamic interrelation between poetic voice and reader, subject and object, agent and action.

Readers of the poem recite what looks like an exercise in metaphor:

We are the porous rock in the stone metate

squatting on the ground.

We are the rolling pin, el maíz y agua,

la masa harina. Somos el amasijo.

Somos lo molido en el metate.

we are the comal sizzling hot,

the hot tortilla, the hungry mouth.

We are the coarse rock.

We are the grinding motion,

the mixed potion, somos el molcajete.

We are the pestle, the comino, ajo, pimienta,

We are the chile colorado,

the green shoot that cracks the rock.

We will abide. (103-4)

By participating in this incantatory recitation, the reader becomes a shaman giving voice to the bilingual metaphors that bring a communal, abiding perspective into being, one that unites the reading public to an expansive identity that includes object and action, rolling pin and grinding motion. Note, for example, the enjambment joining the first and second lines, which affirms the identity of speaker, material, formed tool, and action. Such lines enact Anzaldúa’s exhortation to abandon the tradition of “the Western Cartesian split point of view” that separates subject and object. Instead of Cartesian dualism, Anzaldúa’s work enables readers to “root ourselves in the mythological soil and soul of this continent” (90). Our “soul” could be so rooted in the indigenous beliefs of our “soil” that the very perspectival and ontological distinctions between both words figuratively vanish as their sonic resonance—soil, soul—indicates their identity.

The very term “art” (88) for Anzaldúa appears as a conceptual category of false, violent separation. She rejects the New Critics’ desire for organic unity, which she characterizes as the Western “aesthetic of virtuosity” (89). Such an aesthetic values the concepts of the art object’s “wholeness” and its “internal meanings,” which are artificially, forcefully separated from context and spectatorship, use and ritual, collaborative creation and community. Western art, she writes, strives “to manage the energies of its own internal system such as conflicts, harmonies, resolutions, and balances” (89–90), and it does so by erecting conceptual barricades around the art object. For Anzaldúa, the frames and velvet ropes of museums, as well as the very category “art,” decontextualize, say, a tribal mask from the performance rituals and communal practices that had imbued the mask with its mythic power.

By insisting that her works are “performances” and decidedly not “inert and ‘dead’ objects” (67), Anzaldúa participates in what the art historian Michael Archer calls the art historical “expansion of the field.” The “field” in question includes the practice and study of art, art criticism and history, and the “expansion” involved the demolition of the traditional “cornerstones” that had sustained the very definition of art. 16 Instead of thinking of the production of art as the creation of unique, special objects, artists turned to performances that encouraged audience participation. Artists dissolved the conceptual frame that separated the art from its audience and also distinguished the works of art from mere objects in the world. The “understanding of art as a set of products,” writes Archer, “[gave] way to the idea of it as a process that is coextensive temporally with the life of the artist and spatially with the world in which that life is lived” (72). The spatiotemporal “coextension” between art and life appeared so complete that the terms “art” and “representation” no longer seemed adequate to the proponents of the art field’s expansion.

I invoke this art historical context to show how Anzaldúa participated in a profound art historical shift. She does not merely reject “Western” notions of art; she references such concepts as “the frame” and “autonomy,” activates them, and ultimately renders them inadequate. When she was almost finished composing Borderlands/La Frontera, for example, she writes, “[i]n looking at this book that I’m almost finished writing...I see the barely contained color threatening to spill over the boundaries of the object it represents and into other ‘objects’ and over the borders of the frame” (88). Anzaldúa compares her book to a work of mixed media, the ambiguity of which seems to complicate a simple identification of what remains within the work (as representation) and what remains without (as objects in the world). The “object” her work “represents” appears already to be within her work as representation, almost bleeding onto “other ‘objects’”— a word presented in scare quotes meant to indicate the inadequacy of the term. Despite this ambiguity, however, her language ultimately maintains the integrity of “the borders of the frame:” the color of the represented object “threatens” to spill over (but it does not) while the “frame” she invokes “barely” contains this color (but it does). One of the most vocal critics of the aesthetic of artistic autonomy, here, appears to momentarily sustain what for a lineage of modernist critics and artists constituted that autonomy: the frame.

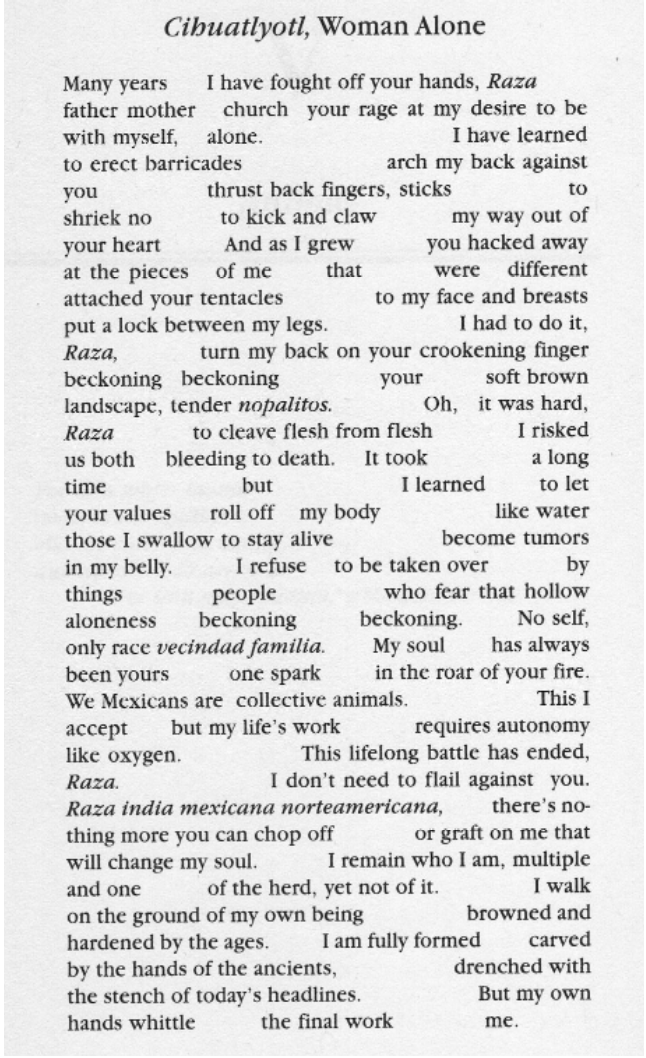

Anzaldúa not only mentions the frame in passing; in the poem “Cihuatlyotl, Woman Alone” she foregrounds the frame’s primacy for the activation of what she explicitly characterizes as artistic “autonomy” as such. (Figure 1) The work is such an integrated whole that it produces the conditions in which paraphrase can only inadequately (heretically) describe the poem’s integral structure. Notice how the poem’s justified margins produce a frame that performs precisely the function that Anzaldúa rejects in “Western art”: the containment and management of “conflicts, harmonies, resolutions, and balances.” The poem depicts a conflict between the singularity of the titular “woman alone” and her community, and it explicitly connects that conflict to a desire for “autonomy.” “We Mexicans are collective animals,” admits the speaker, “This I / accept but my life’s work requires autonomy / like oxygen.” Whereas Anzaldúa’s recitation above (“We will abide”) unproblematically invokes a communal “we” that dissolves boundaries, this framed poem now highlights the speaker’s desired detachment from a community that would “put a lock between [her] legs,” policing her sexuality and restricting her creativity. The formal imposition of the marginal frame dramatizes this social imposition of sexual norms by constraining the poet’s agency. That is, the automaticity of the justified right margin performs a restrictive function by mechanically determining how many letters do or do not fit within a given line. 17 The margin’s restrictions thus take away what amounts to be the poet’s paradigmatic source of power: the poetic line as such. The internal spacing within each line, however, functions as the poet’s insistence on remaining the agent who decides which words will end a given line, thereby activating the line’s potential enjambment. And the lines’ internal spacing activates the gaps between words, converting a spatial pause into a line’s caesura. So, for example, the pointed pause indicated by the spatial isolation of the word “alone” in the poem’s third line—“with myself, alone. I have learned”— reinforces the line’s depiction of the poet’s isolated self-education. And this line’s break (“I have learned / to erect barricades”) visually invokes the barricaded self-isolation the poetic voice describes. Both the pause and the line break can be read as meaningful because nonarbitrary. The spacing within the lines marks the poet’s creation of the conditions in which she could exercise her constrained freedom to choose. The poet must exert a sense of self-sufficiency separate from the “collective,” a solitary sense of self-making reinforced by the autonomy of her “work.” The marginal “frame” could be read as dramatizing the separation of this work, functioning as an emblem of containment that reinforces the work’s internal coherence by seeking to produce it.

FIGURE 1. Gloria Anzaldúa “Cihuatlyotl, Woman Alone” from Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 175.

In her activation of what could otherwise remain an arbitrary fact about a poem—its margins—Anzaldúa appears to be like the modernist painters celebrated by the art critic and historian Michael Fried. 18 Rejecting the art historical “expansion of the field,” Fried instead championed work by painters including Frank Stella, who sought to integrate whatever was on the surface of the canvas, the depicted image, with the material facts of the canvas itself. On Fried’s view, Stella’s paintings sought to integrate the depicted image into the support to make the work a unified whole. The activated frame of these modernist works of art could thus be read by Fried as thematizing the ontological distinction between the work of art and mere objects in the world, between the form of intended art and the contingent shape of natural objects. Anzaldúa, like Fried’s Stella, activates contingency and renders it intentional and thereby meaningful. Her poem not only mentions the speaker’s desire for “autonomy,” it displays the conditions of its possibility.

But we can understand the apparent contradiction between Anzaldúa’s explicit rejection of the Western notion of art’s autonomy, on the one hand, and her activation of that autonomy as emblematized by the frame, on the other, by analyzing how Anzaldúa’s invocation of the frame serves a dual function. As I have tried to show, the frame produces the conditions for the establishment of the autonomy that her work needs by restricting the speaker’s agency. This agency, however, simultaneously registers as trauma. The efforts to reclaim the poetic line could be read as her efforts to extricate herself from a restrictive albeit familiar community, a painful extrication that the poet metaphorically figures as an act of “cleav[ing] flesh from flesh.” The textual gaps thus simultaneously dramatize the poet’s agency and the resulting trauma of this agency—the remaining open wounds resulting from the “cleaving.” The conflict between the speaker and the addressed “Raza” continues throughout the poem until the speaker declares “I remain who I am, multiple / and one,” a declaration that refuses to coalesce into a reductive “we,” while nevertheless acknowledging the multiplicity that comprises her speaking “I.” This is not a resolved synthesis but a remaining uncomfortable contradiction: she is “of the herd, yet not of it”; she is simultaneously “carved / by the hands of the ancients” but also self-formed: “my own / hands whittle the final work me.” She is part of the Aztec Cihuatlyotl invoked by the title (a part of the “ancient” group of women), yet simultaneously the titular “woman alone” (her own self-creation), a contradiction that readers could understand (New Critically) as held in stasis by the title’s comma and contained by the poem’s textual frame; more accurate to Anzaldúa’s project, however, this comma should be seen as the “open wound” that is for her the border itself. 19

Anzaldúa, then, enables in her readers a perceptual shift away from the Cartesian dualism that separates subjects and objects and privileges rationality over the fundamental importance of the body. Part of achieving what she calls a “Mestiza consciousness” instead requires the activation of “la facultad” (60), an embodied, primordial faculty that disrupts habituated patterns of cognition and sight. Anzaldúa wants to help her readers see differently by enabling a perspective that could reject the separation between work and world. If, for a certain understanding of modernism, the frame is crucial for the ontology of the work of art, for Anzaldúa the frame appears as an enforced constraint that would confine the body—not “object”—that is her work. She invokes the modernist frame but pokes holes in the hermetic space it would otherwise create. This activated perspective could enable one to see a work not as a self-contained unified whole; instead, readers are called upon to witness the trauma of a torn body. Anzaldúa, in short, shows her readers a frame but she teaches us how to render that frame invisible.

If Anzaldúa’s activation of “la facultad” is meant to get us to, as she puts it, “see in surface phenomena the meaning of deeper realities, to see the deep structure below the surface” (60), the question we should ask is if this “deeper reality” is the one created by, say, a base’s relation to a superstructure. Does la facultad enable us to pierce through ideology and discover causal explanations? By teaching us to see a body instead of a self-contained work of art, Anzaldúa could be understood as participating in the “Latin Americanist criticism and theory” described by Eugenio Di Stefano and Emilio Sauri. For them, this criticism and theory celebrate the “invisibility of the frame within postmodern and poststructuralist accounts of the text and the work of art” but thereby also make structural inequality invisible: “the invisibility of the structure that creates class inequality in neoliberalism.” 20 Referencing post-dictatorial Latin American literature since the 1980s, Di Stefano describes how efforts to advance human rights were aided by art that highlighted “torture, mutilations, and other corporeal injustices,” art that “dr[aws] attention to, and raise[s] awareness of, the atrocities perpetrated by the dictatorships in countries like Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay.” 21 This noble effort, however, was hampered by its failure to explain the causes of torture. The call for human rights came to replace the explicitly political projects that had been critical of dictatorial regimes. As Di Stefano suggests,

That is, while making violence visible, the discourse of human rights also renders invisible the reasons behind that violence … by highlighting corporeal injustice, the discourse seeks to eliminate the division between art and life (or art and politics) so that the pain of the victim can somehow become that of the reader or the spectator. In other words, human rights want to render invisible the work’s aesthetic status so the reader can be transpired into a kind of witness of a horrific event. In short, insofar as the logic of human rights imagines the violence and the pain of the other as our own, it does so by vanishing the aesthetic frame that divides the textual witness and the reader or spectator. (3)

The political approach that concerns Di Stefano replaces the primacy of meaning with affect, which he connects to the artistic approach that dissolves the distinction between the autonomy of art’s meaning and the world and readers, which appear to determine the art’s meaning. Instead of analyzing and evaluating the political and economic state of affairs, an audience is compelled to engage in an affective experience not necessarily connected to a causal explanation.

Insofar as Anzaldúa enables us to see a world full of hatred and violence against identities instead of one that is fundamentally structured by class, she risks conflating the problem of exploitation with that of the failure of recognition. The solution to one type of problem requires a shift in perspective that enables an appropriate affective response; the solution to a categorically different kind of problem, however, requires that we see the structure as such and actively seek to change it. Insofar as Anzaldúa teaches us how to see bodies and trauma instead of structure and form, she risks fundamentally altering our perspective while leaving the structure intact.

Whereas the evacuation of political beliefs and the celebration of embodied identities constitute a problem for Di Stefano and Sauri, it indicates the path toward a more progressive politics for the scholar John Beverley. In Against Literature (1993), he argues that writers’ claims to “speak for” others cannot help but be compromised by a “vertical model of representation,” in which “elites” claim to represent the voice of the poor by positioning themselves as this voice while nevertheless maintaining their self-interest. 22 Beverley, however, also argues that “Chicana feminist and lesbian writers like Gloria Anzaldúa are using poetry and narrative to redefine and reenergize a previously male-centered identity politics, preparing the ground for the emergence of new forms of liberation struggle” (xiii). For him, these feminists “do not just ‘represent’ a political-legal practice that happens essentially outside the university”; instead, “the contemporary women’s movement passes through the university and the school system” (18, original emphasis). Feminists do not “represent” a practice, nor a community benefiting from that practice. They exist within and flow through the university as that community. And insofar as these women maintain the integrity of their identity, one not subsumed by the institution, the forms and methodologies they create and employ will be “horizontal” because they will not represent the voice of others so much as serve as their synecdochal embodiment.

Beverley offers the testimonio genre as an example of an alternative “horizontal” “position of enunciation” (18) that removes the intermediaries and allows people to speak for themselves. 23 For Beverley, Rigoberta Menchú’s testimonio is not representing the Guatemalan poor as, say, the novelist Miguel Ángel Asturias does, because the voice of her testimony is the voice of the Guatemalan poor. 24 The danger in treating Menchú’s testimonio as the voice of a cultural identity, however, is that this treatment can preemptively resolve a fundamental contradiction evident throughout Menchú’s testimonio: whether her call for global attention is meant to highlight a way of life that is the product of a culture under threat (which should thereby be respected and preserved) or whether she is showing a way of life that is the result of poverty and labor exploitation (and should, therefore, be fundamentally changed). Indeed, we need only turn to the reception of her testimonio to see how a focus on her identity evaporates what Menchú might actually believe. The original Spanish title of the testimonio is Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú y así me nació la conciencia (1983) (“My name is Rigoberta Menchú and this is how my consciousness was born”), yet it was translated as I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala (1984). The original foregrounds how her identity is relevant in relation to a causal explanation of how she came to believe what she believes; the latter title elides her politicized consciousness and instead highlights her identity and subject position. So, although Elizabeth Burgos-Debray argues that Menchú’s testimonio was “a political campaign, not anthropology or literature,” it achieved notoriety within the culture wars of the 1980s, where it was subsumed by the discourse of diversity and cultural recognition. 25 A campaign meant to change international opinion about the efforts of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP) against the Guatemalan army became embedded in a discourse that centers on the preservation of an identity and respect for its difference. So, although there is a genuine desire to hear the silenced speak, the efforts to neutralize representation and the resulting evacuation of beliefs ultimately perpetuates this silence. It does not matter what Menchú might actually want or what she believes; what matters is that she resists cultural encroachment and that her way of life—what she characterizes as emerging from “poverty and suffering”—persists. 26

For Beverley, identities as such seem to share a common vision across all classes, which is why Beverley states that “all politics, including our own, is identity politics, so that the issue is not so much identity politics as such, but rather whose and what identity politics.” 27 If the problem is “male-centered identity politics,” a solution begins with the replacement of male identities with those of women. In this account, the beliefs women might hold appear so firmly fused to their identity as to render disagreement and misrepresentation impossible. This characterization of embodied belief is a problem, of course, because not all women advance the same political views.

Michael Soldatenko’s Chicano Studies: The Genesis of a Discipline (2009) similarly highlights academia’s “masculinist language” of “hard facts, science, and power.” 28 He argues that Chicanos had wanted to change academia radically but succumbed to its sexist, biased methodologies, which professed the virtues of objectivity, “scientism and empirical methods” (4-5). For him, Anzaldúa and Moraga’s edited volume This Bridge Called My Back marked a watershed and offered a necessary corrective to what Chicano Studies became as it gained institutional recognition (28). Soldatenko argues that the Third World Feminism This Bridge collectively articulates signaled a return to Chicanos’ original methodological radicalism and thus paved the way for subsequent feminist oppositional epistemologies that followed in the wake of its publication. Instead of offering truths that are objectively true, these epistemologies foregrounded the subjectivity of knowledge gained through lived, embodied experience. Chicana feminists fused their embodied perspective to their methodologies, what Cherríe Moraga called a “theory in the flesh.” 29

One way to characterize this intervention would highlight how previous academic methodologies had started from erroneous premises, made faulty assumptions, and therefore reached false conclusions. Feminist writers presented experiential evidence that spoke of their specific situations more accurately. Yet this critique of “academically” achieved conclusions presupposes that there does exist a truth that such academic methods are not making available. The very effort to evaluate and discard flawed (because biased) methodologies is the very reason for invoking objectivity as the ideal in the first place, as objectivity is meant to serve as the (however unobtainable) measure with which to assess one’s methods. The practical implications of the critique of objectivity thus cannot discard or replace one epistemology for another better one (however “better” is defined) without ensuring that objectivity remains the evaluative measure. The act of replacing one general “perspective” for another begs the question of grounding, which cannot be that of embodiment or cultural nationalism without producing immediate suspicion. This problem leads Soldatenko to acknowledge how “[a]t the center of this [Chicano methodological] perspectivist project was self-consciousness. A danger, however, existed on trying to ground this self-consciousness. It was easy to step from a perspectivist analysis over to essentialism and nativism” (92). His account of a Chicano “perspectivism” seeking to ground its self-consciousness paradoxically—even if momentarily— presumes the possibility of an ungrounded, free-floating “self-consciousness,” thereby reproducing the very problem that the critique of objectivity was meant to highlight: that of the impossibility of disarticulating subjectivity and objectivity, embodiment and perspective. This invoked “self-consciousness” presupposes a position outside of the self on which that self could be examined and evaluated. The point of the critique of objectivity was to argue that there is no such position.

The problem of methodology is thus compounded when it is characterized as a problem of objectivity and supposedly solved with self-conscious perspectivism. Like Beverley, Soldatenko appears to deactivate the possibility of arguing about what constitutes the truth (about, say, political strategies) because the conclusion this kind of argument entails must be that “our” methodologies are simply our own, as opposed to “theirs.” This approach appears to make political solidarity across different identities seem impossible. You have your perspective; I have my own. We do not disagree so much as we have differences in experiences.

Because Soldatenko’s historical account does not attend to the literature produced by Mexican Americans, he laments how “almost a decade would pass before Chicanxs would take seriously the promise of This Bridge” (167), and this lament echoes his overall assessment of what went wrong with Chicanx Studies as such. For him, early attempts to develop radical methodologies were displaced as efforts were directed “increasingly towards the arts” (26-7). He seems to argue that if only Chicanxs had continued to develop their critiques of methodological objectivity, Chicanx Studies itself might have remained heterogeneous and fluid instead of ossifying within the university. Yet this turn to the arts in the late 1960s and early 1970s was understood as producing the very standpoint epistemology Soldatenko would like to have seen developed. 30 Insofar as positivist empiricism and its faith in methodological objectivity led to reductive social scientific descriptions of Mexican Americans, literature written by Mexican Americans was produced to offer a potentially radical discursive alternative. Indeed, the very assumption underwriting Chicanx literature as such depends on a shared “perspective” (however heterogeneous) that operates as the necessary principle of selection with which to determine which kinds of experiences count as producing a “Chicano.” The consolidation of this literature suggests the specificity, the uniqueness of the delineated/delineating perspective: Chicanos qua Chicano brought something to bear on American literature that was not reducible to that literature yet was an integral part of it. That literature, however, could subsequently be seen as inadequate because overtly biased, exclusionary, and misrepresentative. So, if literature could be seen as offering a radical alternative to positivist empiricism and methodological objectivity, it would need to determine how to represent others without distortion.

Framing Chicanas’ Stories

Although Soldatenko’s research does not identify how a turn to the ontology of perspective fails to solve the epistemological problems of representation, his account helps us contextualize Ana Castillo’s rejection of academic methodologies and her explicit turn to literature. Castillo describes how the archival research she conducted for her M.A. thesis on “Amerindian women” recovered only “stereotypes”: “At best I found ethnographic data that ultimately did not bring me closer to understanding how the Mexic Amerindian woman truly perceives herself since anthropology is traditionally based on the objectification of its subjects.” 31 According to Castillo, women are not only excluded from institutions as students and faculty, their voices are also omitted from the university’s disciplines as studied, speaking subjects. When the history of women is studied, its complexity and specificity tend to be reduced methodologically (in the objectification of women as studied objects). Castillo thus turns away from academic research and its methods and instead writes what she calls an “autobiographical poem” in which she “liken[s]” her struggles in academia to those of the Indigenous woman whose voice she was trying to unearth:

The Indian woman carries her flag

over her face

blood stained

her scars run

like old roads through her land

and the Indian woman does not complain (Massacre 8)

However much Castillo wants to hear the voice of this unspeaking woman, the poem does not ventriloquize what the woman might say. The poem rather shows her perseverance. Yet, later commenting on the poem, Castillo comes to realize how such a woman “is a part of my genetic collective memory and my life experience […] I stand firm that I am that Mexic Amerindian woman’s consciousness in the poem cited above and that I must, with others like myself, utter the thoughts and intuitions that dwell in the recesses of primal collective memory” (Massacre 17). “Collective memory” unites their voices. She imagines the conditions in which she does not try to represent what the Indian woman might say so much as provide her a conduit through which that woman can speak for herself. She does that by converting the question of representation into the assertion of an identity: “I am that Mexic Amerindian woman’s consciousness.”

Castillo’s turn to literature highlights how the complexity and specificity of the history of women tend to be reduced to limiting disciplinary boundaries, what Emma Pérez describes as the “systems of thought which have patterned our social and political institutions, our universities, our archives, and our homes.” 32 Relating her own experiences in graduate school, Pérez tells how “[a] historian must remain within the boundaries, the border, the confines of the debate as it has been conceptualized if she/he is to be a legitimate heir to the field” (xiii). Such boundaries distortedly “frame Chicana stories” (xiii) and “predispose us to a predictable beginning, middle and end to untold stories” (xiv). Understood with this methodological criticism in mind, the very form of Castillo’s epistolary novel The Mixquiahuala Letters (1986) can be seen as an implicit critique of such distorting narrative “frames.”

The epistolary novel opens with a note to the reader that offers three distinct sequences for encountering the book’s letters, each of which orders the narrative towards a “conformist,” “cynical,” or “quixotic” reading. A fourth option, “for the reader committed to nothing but short fiction,” offers the group of letters as “separate entities.” 33 This note (as does the novel’s dedicatory note) pays tribute to Julio Cortázar, whose novel Rayuela (1963) similarly opens with a “Table of Instructions” offering two different sequences for reading the chapters. Castillo builds on Cortázar’s formal experimentation by highlighting the salience of the reader’s perspective, implicitly echoing the insight of Hayden White’s Metahistory (1973). For White, the writing of history tends to assume generic forms of “emplotment” (romance, comedy, tragedy, and satire), which provide a structure and narrative arc to unconnected events. 34 For Castillo’s novel, the reader’s preference dictates the narrative form that organizes what could otherwise remain “separate entities,” which is to say non-teleological episodes unstructured by emplotment. So, although The Mixquiahuala Letters is not a historical novel, its form bares the constructed nature of “history.” 35 The novel offers an implicit critique of positivist epistemology that echoes Jean-François Lyotard’s account of postmodernism, which became available to an English audience with the translation of La condition postmoderne in 1984. 36 Lyotard’s description of the gradual dissolution of the “grand narrative” meant that the belief in empirical, scientific progress could no longer be overtly declared without betraying a degree of naiveté.

Castillo’s formal innovation is the product of a search for adequate forms of representation that is itself dramatized in the novel. The character Teresa makes a return trip to Mexico—which she calls “Mexico revisited” (52)—that is motivated in part by her desire for a spiritual homecoming. As Teresa puts it, “the Indian in me” sought “a place to satisfy my yearning spirit...a home” (52). This yearning leads her to “seek the past by visiting the wealth of ancient ruins that recorded awesome, yet baffling civilization” (52). Once Teresa arrives at the ruins of Monte Albán, however, the “awesomeness” of the ruins matches their overwhelming effect on her. She cannot “respond as immediately with a poem” as she would like. So instead of functioning as a symbolic home for Teresa’s “Indian” spirit, the ruins present her with a question of representation: how could Teresa possibly delineate the ruins and their effect? Rather than attempting to write a poem, Teresa turns to the “snapping of pictures” (62). Photography’s immediacy proves useful to the Wordsworth-like poet who prefers to take some time to process the intensity of the experience because the photographic medium can bracket the question of representation she faces. Insofar as snapshots present Teresa’s visual perspective without rendering her thoughts about them, the photographs do not represent the ruins so much as they offer records of their presence. The photographs share an “indexical” relation to the ruins that looks more like a relation of identity than one of representation. The snapshots are not representations of the ruins so much as they are the ruins’ trace. Just as Castillo’s poem I cite above does not represent the unspeaking indigenous women’s voice so much as provide the medium for this voice to speak for itself, here the photographs do not represent the ruins (as a poem or painting would) so much as allow their presence to be recorded.

This relation of (near) identity can temporarily foreclose the question of representation, yet this question remains ultimately unanswered. The snapshot risks functioning merely as a kind of souvenir but not as an expression, a formal externalization of the effect the ruins have on Teresa’s sense of self. This search for a “home” for her inner “Indian,” after all, is why she is there. When her traveling companion Alicia, a painter, returns to New York after their trip, she “arrived with souvenirs and sketches” that she too must try to “piece together” (48) if they were to mean anything. “You sensed, in the end,” Teresa writes to Alicia, “it all had to have meant something, that, if we were able to analyze, it would be pertinent, not just to benefit our lives, but womanhood” (53). The question of representation takes on a heightened sense of urgency and significance: if their experience might count as somehow representatively “pertinent” to “womanhood,” their recollections must be analyzed and formally rendered. Someone needs to represent their experience responsibly, but how? The question of representation temporarily foreclosed by the logic of the snapshot reappears as the return of the repressed.

For the painter, an answer to the question would require “piecing together” the trip by using the souvenirs as inspiration for her work. Years after their trip, however, Alicia confesses “never having been able to pull apart its entanglement in [her] memory,” suggesting the lasting power of the trip’s influence but also her inability to externalize this influence in her painting (53). Teresa, however, does eventually begin the process of retrospective analysis (“untangling”): she comes to “open the sealed passages to those months” and to “writ[e] about it” (53). Indeed, when she later refers to the trip by the name she gave it, she now does so more formally—Mexico Revisited— italicizing and capitalizing the words as if they were the title of a book instead of a name for a set of memories (53). Teresa, we might say, can no longer forestall the problem of representation, and Mexico Revisited will constitute her effort to externalize her thoughts. And the form that Mexico Revisited will take is provided by The Mixquiahuala Letters itself: the epistolary novel. The novel consists only of the letters/poems that Teresa writes to Alicia. Like snapshots— which cannot but be ontologically perspectival— the letters only provide Teresa’s perspective (readers are never privy to Alicia’s responses). But the most significant fact about the novel’s use of the epistolary form is Castillo’s refusal to order the letters into a sequence, a refusal that extends an invitation to the reader to determine the meaning of Teresa and Alicia’s experience.

The Mixquiahuala Letters, then, takes the neutralization of the problem of representation offered by photographic snapshots and uses it to inform the structure of its epistolary form, the letters functioning as linguistic snapshots that, like photographs, could be perceived as not in themselves meaning anything, their ultimate significance becoming a product of the reader’s preference. 37 This formal innovation converts an epistemological problem (how one can know something) into a practical one (how one can employ the conventions of a genre to exploit its mediating limits), a neutralization that captures the postmodern insight of multiplicity. “There is no pure, authentic, original history,” is how Emma Pérez makes the case against positivist historical empiricism, “There are only stories—many stories” (xv). Insofar as the stories that circulate about women (when they circulate at all) tend to reduce them to flat, static stereotypes, The Mixquiahuala Letters instead offers “only stories—many stories” about two women as framed by Teresa’s memory and narration, which the novel’s form exposes as a mediating perspective that it will not privilege as the decisive narrative of the novel (i.e., what “really happened” between Teresa and Alicia). The logic of the snapshot presents a perspective without determining a singular meaning, and the non-prescription of the approach enables a reader-determined experience wherein the reader’s preference becomes “pertinent” to the work without having been represented within it.

Castillo’s formal innovation instigates that experience but does not fully determine it, and this open-endedness ultimately insists on the primacy of the reader’s experience instead of the novel’s form. The letters’ lack of order postpones the question of “untangling” and leaves it up to us. We in effect become Teresa sorting through the snapshots and souvenirs, imposing a narrative that will provide them with their significance. Although the problem of representation has not been solved so much as displaced, our consciousness of its limitations has been raised. On the view offered in Mixquiahuala, “history” could be but a story one tells that connects one thing to another. We would not disagree with our various narrations of such stories because your version will simply be different from mine. Disagreement is neutralized, but so is the possibility of ever getting the story right, leaving us with merely differing perspectives.

How to Survive

But if the problem with represented knowledge is one’s subjective perspective, then either there can be no truth that perspectival beings can understand once those truths are embodied, or the only truths we could be certain about are those that we embody. But, following Derridean-influenced accounts, if self-knowledge already fractures the knower from the known because of mediation as such, then something like certainty cannot be consciously possible because of the separation such mental mediation produces. The problem with certainty would not only be that of the impossibility of objectivity but also the impossibility of maintaining a radical self-same subjectivity, an identity rendered so intensely that it could never be different from itself.

Alma Luz Villanueva’s novel The Ultraviolet Sky (1988) presents the conditions of such a self’s possibility, one so fused to itself that it cannot be alienated in history. By intensifying Castillo’s invocation of “genetic collective memory” that links one’s present experiences to the past, Villanueva carnally connects the past to the present by encoding history into blood. Indeed, the world as such comes to look like the self writ large. Such a self would have no need for artistic mediation, which comes to appear as insufficient and reductive. This is why, in Ultraviolet, even the logic of the snapshot appears insufficient because formal. So, whereas in Mixquiahuala photography’s perspectival nature served as the temporary, strategic solution to the problem of representing Mexican ruins and their relation to Teresa’s sense of self, Ultraviolet presents a problem that photography itself cannot address. Julio, a photographer whose work includes beautifully rendered “large black and white photographs of the Mexican pyramids,” has the ambition to take a self-portrait, yet the “photograph he longed for” was one of “his face” as he waited for the Viet Cong during combat. 38 Not only does he want to be in the state of absolute life-or-death absorption, he also wants to be the one to take the picture. The photographs others took of him in Vietnam “made him look like a caricature of a soldier” (36), the difference between being a soldier engaged in battle and simply looking the part appearing absolute. Being completely absorbed and watching oneself be so absorbed are actions that are, as Todd Cronan helpfully writes, “ontologically” distinct. 39 The state of absorption would be broken by the act of taking a picture. “The problem,” as the novel puts it, “was he could only see it from one angle and there were many” (37).

This diagnosis of the problem aptly describes the specificity of the photographic medium but also Julio’s inability to see the world from a perspective that is not his own. Like Anzaldúa’s critique of the desire for artistic “mastery” found in “Western art,” which seeks to be “whole and always ‘in power,’” Julio remains stubbornly trapped by his perspective, mentally entrenched in war’s psychic trenches. When he teaches a Beginning Photography class, his advice to students sounds like he was “giving a war cry in the genteel, silent classroom”: “I want to see a picture of all of you, every one of you, waiting for your mother-fucking enemy … Shoot it, you stupid bastards, before it escapes—before it gets you” (36). Photography, here, becomes an act of aggression. When the desired “shot” one wants to take is of oneself and at the enemy, “before it escapes—before it gets you,” art becomes war, and one’s self becomes the enemy. Unlike Julio, who remains stuck within an antagonistic perspective, Rosa, a painter, can look in the mirror and “fe[el] herself looking back at herself like an old friend, a patient friend” (275). To see oneself not as an enemy but as a friend requires a mental shift Julio seems unable to make.

The novel marks this perspectival difference between Rosa and Julio as crucial because it connects Julio’s ambition to an insidious will to formal mastery. Rosa, however, learns to recognize the limitations of her artistic practice. Reminiscent of Castillo’s Mixquiahuala, Rosa and her best friend Sierra, a poet, take a brief trip during which they discuss their work. Rosa describes her ongoing struggle with a painting of a lilac sky. “It’s the elusiveness of that color that’s so distracting,” she tells Sierra, “I mean, the sky is always changing” (88). Later in the trip, when Sierra suggests to Rosa that she try writing poetry instead, the painter replies, “No, not me. I freeze up when I know my words will be formal or permanent. Color gives me room to breathe, imagery can mean something else” (90). So, although the “elusiveness of color” constitutes part of the representational problem she must overcome to complete her painting of the lilac sky, it is precisely this elusiveness that makes painting an attractive medium for her art. Because “color” is less “formal” and “permanent” than language, she suggests, it can be more ambiguous because its connotations can shift.

Indeed, by the end of the novel, Rosa will recognize how the painting she wants to complete is ultimately impossible to render because she wants to capture a shade of lilac that is ultraviolet, un-representable by visual color. Painting might be less “formal” and static than language, yet it is ultimately too formal to capture a shifting sky, the color of which cannot be seen. Rosa comes to understand that she can “only witness what it does,” only experience its effects. In the face of the un-representable, one could, like Julio, remain stuck and aggressively insist on formal mastery. Or one could, like Rosa, shift one’s perspective and abandon an ambition that is ultimately futile.

This perspectival shift becomes the solution to the novel’s central recurring question, which is simultaneously global and personal: “How will we survive?” (17, original emphasis). How can a world subsist when its inhabitants continually threaten to destroy it and each other? How can a woman and man coexist if their expressions of intimacy become a battle? The novel frequently refers to a requisite sense of “harmony” and “wholeness,” suggesting that the answers to these questions, whatever they may be, must strive for a “balance” between the forces of creation and destruction, love and hate. But while the ambition to achieve these states is perhaps more easily attainable in art than in the world, in the novel, the point is not to strive for a formal mastery that is otherwise unobtainable—art’s unity and wholeness, harmony and balance separated from the world’s incoherence. Instead, one can strive to experience an extension of the non-alienated self in the world, achieving a totality with what Rosa calls “The whole damn thing” (67). Whereas the passionate yet aggressive sex with Julio leaves Rosa feeling as if “[s]he didn’t belong to herself” (53), when she masturbates by the seashore, she “blend[s] her body with the sea until the union was complete” (41). Just as art can be war when the self is an enemy, and just as the will to formal mastery can be homologous to the will to domination, sex can be war when the self is threatened by a desire that compromises one’s self-possession. Masturbation becomes a way for Rosa to affirm herself and fuse this self with the world via a “complete orgasm” (41).

Like masturbation, aesthetic experiences unmediated by extrinsic forms fuse “self” and “world.” This is why Rosa compares a flamenco dancer’s orgasmic performance to self-birth and uses it as a model for her ambition: “Tonight [the dancer] gave birth to herself, hands raised toward an unseen sky. Yes, Rosa thought, that’s what I must do.” A flamenco dancer ecstatically embodies the dance—she is the dance— while her snapping fingers produce “a naked sound compared to the castanets” (28). The sounds are “naked” because they are intrinsic to the dancer’s body. Similarly, words, because they are parts of a conventional system of representation, are not Rosa’s the way that the sound of her voice is hers. “Self” and “art” fuse in a conception of self-initiated, self-birthing described in the novel’s final lines: “she begins to sing, but words feel clumsy to her.... A single sound, a single note, comes out of her mouth, and she repeats it in varying tones until it lets her go. It is longing. It is praise. It is hers” (379). This emanation of herself as voice— which ultimately “lets her go” yet remains “hers”— is a kind of bearing of the self, wherein the newborn self is simultaneously autonomous from and unalienated to the self that births, a self apparently unalienated from the world as such.

By shifting her perspective and by disavowing the will to formal mastery, Rosa can see herself as a friend, a gesture she extends to “Germany, Hitler, blondeness, this opposite of myself” (35). But, true to its internal logic, “Germany” is not actually “the other” with whom one might disagree because Rosa comes to discover that her estranged father was German. This is why when Rosa grabs a gun belonging to a World War II German soldier, a “pain shot right up her arm” and “the image of dead men came to her mind” as well as that of a small German girl in a concentration camp (186). Like the “primal collective memory” that unites Castillo to the past (“I am that Mexic Amerindian woman’s consciousness”), “racial memories” (17) in Ultraviolet Sky are conveyed via the pain that shoots up her arm, reminding her, “That girl, that young girl is me […] it was her thirty-four years ago when she died in a concentration camp” (57). In this world, representation is no longer necessary because beliefs become bodies and “history” becomes blood. Ultraviolet Sky thus implies that if we can no longer naively be certain about our epistemological relation to history, we could instead think of it as ongoing within us, bypassing the need to learn and to know it, envisioning our ability to remember and to experience it.

The novel’s utopian world would comprise a global community unified by a singularity of affective, experiential beings unhampered by disagreement. Rosa concludes that Germans are not the other because the Holocaust represents America’s original sin: “[W]e’re all in that position, globally. To not accept our common reality...is to deny our awareness, our part in it, as a part of it. The whole damn thing” (67). Were we to recognize our common predicament, the very concept of “the other” would lose its intelligibility. Insofar as the fundamental problems plaguing contemporary societies are understood as crimes against identity, the protection of endangered identities appears as the solution. This is why, in Villanueva’s Ultraviolet Sky, an artist writes to Rosa about the “anti-nuclear demonstrations in Berlin” called the “Back to Nature Movement” consisting of German artists “dressed up like Indians.” Rosa smiles at their silliness but also recognizes their laudable efforts to live a more harmonious life with the planet: “they were trying, weren’t they? she thought. They were trying to be Native People. Native People of the Earth” (266). Indigeneity can be a subject position, available to be performed and somehow leading to global salvation. The important fact about the “Native People” (like Rigoberta Menchú) is not what they believe but that they persist.

Villanueva’s Ultraviolet Sky, then, not only dramatizes the primacy of identity, it also imagines the possibility of building coalitions based not on articulated beliefs but on the performance of endangered identities that have developed survival strategies in the face of power that would otherwise destroy them. Such an idea motivates an important oppositional methodology in Chela Sandoval’s Methodology of the Oppressed (2000). Like Rosa, who wonders how to survive the conditions facing everyone (“we’re all in that position, globally”), Sandoval argues that late capitalism has produced a situation in which everybody must face the reality of existential instability, what she calls the “democratization of oppression.” 40 She recommends the strategic performance of the subjectivities that have developed survival strategies. Instead of the “industrial working class” as the agent of history, she posits “people of color, of lesbians, gays, queers, women, or the subordinated” as the actionable subjectivities. In the performative expressions of strategic solidarity, “[i]deology, citizenship, and coalition” would function as mere “masquerade” (31). The efficacy of this approach enables the formation of actionable coalitions across identities and perspectives (you have yours; I have my own), momentary expressions of solidarity that can strategically coalesce to fight oppression. But by potentially eliding the historical, material differences leading to the various forms of subordination, oppression, and exploitation, Sandoval risks eliding the specificity of economic exploitation by treating it as but another expression of oppression within a broader spectrum. This approach in effect empties otherwise fundamentally divergent political beliefs of their content. “To deploy a differential oppositional consciousness” she writes, “one can depend on no (traditional) mode of belief in one’s own subject position or ideology” (30). Such a solidarity is one that nobody has to believe in because beliefs are not what unites us.

“There is the quiet of the Indian about us,” writes Anzaldúa, “We know how to survive” (Borderlands 86). For her, survival means preserving one’s native tongue, which figuratively transcends its status as a system of signs and becomes instead the textual embodiment of an identity. 41 “We,” she writes, “count the days the weeks the years the centuries the eons until the white laws and commerce and customs will rot in the deserts they’ve created, lie bleached … nosotros los mexicanos-Chicanos will walk by the crumbling ashes as we go about our business” (Borderlands 86). The problem, here, with existing “laws,” “commerce,” and “customs” is that they are not ours. But what new laws will be set in place in Anzaldúa’s apocalyptic future? What will replace commerce? Who gets to count in the “we” walking alongside Anzaldúa observing the ashes? The articulation of answers to these questions would be enabled by the concepts that during the past 40 years have been repeatedly questioned and ultimately rejected: the possibility of artistic and political representation, of literature’s capacity to represent a meaning that is not reader-dependent, of political beliefs as being right or wrong regardless of its believers’ subject positions or methodologies, and of the very possibility of changing the mind of others.

Social Deprivation

I have argued that Anzaldúa, Castillo, and Villanueva highlight the shortcomings of representation and experiment with form to find a more suitable medium. Their work has the undeniable power to produce a reading public. Readers recite Anzaldúa’s incantations and see themselves as sharing something like a communal spirit, while those who encounter Castillo’s “primal collective memory” can see themselves as capable of resounding the voices of the violently silenced. Readers of Villanueva’s work experience the profundity of self-acceptance and encounter a dramatized solution to save the planet and each other. What I have tried to show, however, are the limits of their innovative fictive technologies for debates about epistemology (about historical knowledge, about knowledge as such) and politics (about establishing long-term coalitions able to enact change). I argued against the scholars who have treated personification and performance as viable solutions that enable resistant methodologies and circumvent the shortcomings of representation. These scholars have not acknowledged how the conversion of text to body, meaning to experience, and political beliefs to identities (I have mine; you have your own) has had the effect of diminishing the role of competing political beliefs and deactivating the possibility of political solidarity.

I would like to conclude by turning once more to Castillo’s The Mixquiahuala Letters to demonstrate the implications of this argument. In a letter in which Teresa reminds her friend Alicia about the fervor of the Chicano Movement, she describes the years “1974, ’76” as part of “a moment of Southwestern influence, our Aztlán period” (44). The novel as a whole does not claim to represent this “Aztlán period” nor the community involved. Instead, Teresa only writes about her experience. This letter highlights this difference—between a writer claiming to speak for a community and a writer speaking only for herself—when Teresa describes how she participated in a program called “Somos Chicanas, a program about Chicana women by Chicana women, for Chicana women.” This feminist program features women declaring their identity, “Somos Chicanas,” speaking for themselves to themselves. Shortly after this description, Teresa’s letter highlights a different kind of agenda consisting of men declaring themselves communal spokespersons:

The eloquent scholars with the Berkeley Stanford

seals of approval

all prepped to change society articulate the

social deprivation of the barrio

starting with an

Anglo wife, handsome house, and Datsun 280Z in the drive-

way

This passage draws our attention to poetic form, which in turn has the ability to draw our attention to a structure of inequality. In the letter, Teresa turns to the power of the poetic line to render the disconnect between the purported claims to represent a community and what otherwise appears as self-interest. The third line’s lack of a break separating the words “society” and “articulate” suggests the underlying continuity between the status quo and the scholar’s articulation of what they take to be the problem. And the spacing that separates “the barrio” and the description of the scholar’s actions captures a revealing ironic disjuncture. In seeking to secure their positions within the upper-middle class, thereby enjoying the material luxuries this position entails, these academics end up participating in the very structures maintaining the status quo, all while claiming to address the “social deprivation” of their purported barrio.

The passage highlights the mistaken presumption that men can adequately speak about the problems they have not themselves experienced. These men could articulate mistaken views and circulate misguided solutions that do not help and make matters worse. A solution to these problems would involve the replacement of the erroneous men with women advocating for their own needs as women. Work by Anzaldúa, Castillo, and Villanueva places women, queer women, and women of color at the center of conversations rather than accept being dangerously ignored. It remains necessary for those who suffer to articulate their needs and the needs of those who share similar experiences. That viable solution has not been in question in this essay. Rather, I have argued that it would be a mistake to assume that women qua women would automatically share the same political views by virtue of their identity.

I have tried to show how this mistaken assumption appears as one of the entailments of the turn to personification that emphasizes identity over meaning, and performance that prioritizes experience over political (dis)agreements. For the advocates of the identity-based solutions I have analyzed, the problems of misrepresentation exemplified in Castillo’s excerpt could have resulted from a masculinist identity politics and the use of biased methodologies. Perhaps the male “eloquent scholars” used the established academic systems of knowledge instead of creating their own oppositional methodologies expressive of the Chicanx experience. A solution would thus involve the provision of a different identity-based politics and oppositional discourses. In this view, one could replace the male scholars with a different identity that synecdochally embodies the community so that the manifestation of its self-interest would somehow remain expressive of those not as fortunate. This replacement would not change the structure, only the structure’s beneficiaries.

Teresa’s letter does not provide the meaning of “social deprivation.” “Deprivation” could refer to the barrio’s exclusion from the middle class, from college, and from managerial positions. If defined in this way, deprivation would mean something like social marginalization, and its solutions would involve efforts towards inclusion. Or, “social deprivation” could instead refer to economic exploitation, wherein people are not adequately compensated for their labor, do not have access to affordable housing, healthcare, childcare, job security, legal representation, and access to social services. In this view, inclusion into college would not solve the problems produced by low-paying jobs that do not require a college degree. With this latter definition, we could ask if social deprivation was the result of the American economy transitioning away from the manufacturing jobs that previously benefited working-class communities and toward finance and free trade—a transition that began in the 1970s and fully blossomed during the 1980s. 42 In short, it matters how exactly spokespersons define what the barrio needs, and it matters what they are espousing as remedies. If we focus on the identity of the spokespersons while not adequately attending to the causes of the articulated problems and the validity of the proposed solutions, we risk missing the problem of exploitation entirely.

José Antonio Arellano is an Associate Professor of English and Fine Arts at the United States Air Force Academy. Some of his recent essays appear in Race in American Literature and Culture, The Cambridge Companion to Race and American Literature, and post45.org. Arellano is an art critic for the Denver-based art magazine DARIA. His short book Race Class: Reading Mexican American Literature in the Era of Neoliberalism, 1981-1984 is under contract with the Cambridge University Press Elements Series.

Notes:

-

1 Linda Hutcheon, A Poetics of Postmodernism: History, Theory, Fiction (New York: Routledge, 1988), xi. BACK

-

2 The more well-known examples include Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales’s epic poem I Am Joaquín, the speaker of which asserts, “I am the masses of my people.” Message to Aztlán: Selected Writings (Houston: Arte Publico, 2001), 29. See also Alurista’s poems included in Floricanto en Aztlan (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2011), and Tomás Rivera’s writing collected in Tomás Rivera: The Complete Works (Houston: Arte Público Press, 2008). BACK

-

3 Ana Castillo offers “Xicana” and “Xicanisma” as replacements for the terms Chicano and Chicanismo. Ana Castillo, My Father Was a Toltec: And Selected Poems (New York: WW Norton, 1995), xvi. Gloria Anzaldúa identified a transition away from the Chicano Movement to what she calls “the Movimiento Macha.” Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 229. BACK

-

4 For José F. Aranda, Gloria Anzaldúa’s innovative borderlands metaphor offers a necessary corrective to the nationalistic and exclusionary concept of “Aztlan.” Anzaldúa and Chicana feminism can serve as a model for a revitalized “new Chicano studies.” When We Arrive: A New Literary History of Mexican America (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2003), 33. BACK

-

5 For a relevant account of the politics of Chicana visual art produced from 1985 to 2000, see Laura Elisa Pérez’s important contribution Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Alterities (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007). Pérez describes the “socially and materially embodied s/Spirit... consciously re-membered [in the Chicanas’ work], which we are called to witness and act upon...” (25). See also Suzanne Bost, Encarnación: Illness and Body Politics in Chicana Feminist Literature (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010). For Bost, the recurring invocation of childbirth and motherhood can be read as dialectical metaphors that highlight the non-metaphorical fact of embodiment, which is more fundamental to one’s identity than the categories of race, class, sexuality, and nationality. For an interpretive triad that explains Chicana poetry in relation to the terms “woman,” “poet,” and “Chicana,” see Marta Ester Sánchez’s Contemporary Chicana Poetry: A Critical Approach to an Emerging Literature (Berkeley: University of California, 1985). Sánchez focuses on gender and ethnicity but excludes class “because Chicana intellectuals and writers were more conscious of race and gender than of class as factors shaping their lives” (340 n16). BACK

-

6 Elizabeth J. Ordóñez “Body, Spirit, and the Text: Alma Villanueva’s Life Span,” in Criticism in the Borderlands. Studies in Chicano Literature, Culture, and Ideology, ed. Héctor Calderón and José David Saldívar (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), 61. BACK

-

7 Elizabeth J. Ordóñez, “Preface,” in Life Span, by Alma Luz Villanueva (Austin: Place of Herons, 1985), v. BACK

-

8 Charles Hatfield, The Limits of Identity: Politics and Poetics in Latin America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015), 54-55. Hatfield challenges a set of widespread ideas in Latin American cultural studies and literature, including “the idea that cultural practices can be logically justified on the grounds that they are ours; the repudiation of authorial intention and the notion that a reader’s experiences and participation are relevant to a text’s meaning; the notion that we can somehow remember historical events that we never experienced; and finally, the claim that the celebration of cultural difference is a form of resistance to neoliberalism.” Hatfield roots these ideas in the attempt to circumvent the concept of universality, which inevitably suggest that “there are many equally valid truths and that different beliefs, instead of being true or false, are merely the product of different worldviews, epistemologies, epistemic systems, cultures, and subject positions” (3). BACK

-

9 Nancy Fraser, Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis (New York: Verso, 2013), 1. BACK

-

10 Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser, Feminism for the 99 Percent: A Manifesto (New York: Verso, 2019). BACK

-

11 Deborah L. Madsen, Understanding Contemporary Chicana Literature (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 2. BACK

-

12 Gloria Anzaldúa “Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers,” in This Bridge Called My Back, eds. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (London: Persephone Press, 1981), 163. BACK

-

13 Amy Hungerford, The Holocaust of Texts: Genocide, Literature, and Personification (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 4. BACK

-

14 Alma Luz Villanueva, Life Span (Austin: Place of Herons, 1985), 9. BACK

-

15 W. K. Wimsatt and Monroe C. Beardsley, “The Intentional Fallacy,” Sewanee Review 54, no. 3 (1946), 470. BACK

-

16 Michael Archer, “The Expanded Field,” in Art Since 1960 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002), 61. BACK

-

17 This reading was inspired by an account of Susan Howe’s Frame Structures: Early Poems 1974-1979 delivered as a class lecture by Walter Benn Michaels at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, October 21, 2014. The publication dates of the poems collected in Frame Structures is highly relevant, as Howe explored the limits and enactment of postmodern art and theory precisely as “the field,” to use Archer’s term, was being “expanded.” BACK

-

18 Michael Fried’s relevant essays are “Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s Irregular Polygons,” and “Art and Objecthood,” in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). BACK

-

19 The Cihuatlyotl, or Cihuateteo, were a group of women whom the Aztecs considered fallen warriors because they died during childbirth, which was considered similar to taking a prisoner during war. See Mary Ellen Miller and Karl A. Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1997), 61. BACK

-

20 Eugenio Di Stefano and Emilio Sauri. “Making it Visible: Latin Americanist Criticism, Literature, and the Question of Exploitation Today,” nonsite.org (2014): n.p. http://nonsite.org/article/mak.... BACK

-

21 Eugenio Claudio Di Stefano, The Vanishing Frame: Latin American Culture and Theory in the Postdictatorial Era (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 3. BACK

-

22 John Beverley, Against Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 17. BACK

-

23 Beverley defines testimonio as “a novel or novella-length narrative in book or pamphlet (that is, graphemic as opposed to acoustic) form, told in the first person by a narrator who is also the real protagonist or witness of the events she or he recounts” (70). BACK

-

25 Elizabeth Burgos, “Foreword: How I Became Persona Non Grata,” in Rigoberta Menchú and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans, by David Stoll (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2008), ix-xvii. BACK

-

26 Rigoberta Menchú, I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala (London: Verso, 1994), 15. BACK

-

27 John Beverley, Testimonio: On the Politics of Truth (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 22. BACK

-

28 Michael Soldatenko, Chicano Studies: The Genesis of a Discipline (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2009), 4. BACK

-

29 Cherríe Moraga, “Entering the Lives of Others: Theory in the Flesh,” in This Bridge Called My Back, 19. BACK

-

30 John Alba Cutler rightly argues that the “turn to literature” was understood as “an extension” of the critique of social science because literature functioned as “an alternative to social science’s self-authorizing empiricism.” Ends of Assimilation: The Formation of Chicano Literature (New York, Oxford University Press: 2015), 89. BACK

-

31 Ana Castillo, Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994), 7. BACK

-

32 Emma Pérez, The Decolonial Imaginary: Writing Chicanas into History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), xiv. BACK

-

33 Ana Castillo, The Mixquiahuala Letters (1986, repr. New York: Anchor, 1992), n.p. BACK

-

34 “Providing the ‘meaning’ of a story by identifying the kind of story that has been told is called explanation by emplotment …. Emplotment is the way by which a sequence of events fashioned into a story is gradually revealed to be a story of a particular kind.” Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 7. BACK

-