Must the Subaltern Speak? On Roma and the Cinema of Domestic Service

In the weeks following its release on Netflix, the critical reception of Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma (2018) crystallized around a negative review published in The New Yorker by Richard Brody. 1 The review’s main thesis was announced in its title: “There’s a Voice Missing in Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Roma.’” Brody objected to the film’s depiction of Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio), the domestic servant at the center of the film. The character of Cleo was based on Cuarón’s own live-in nanny, Libo Rodriguez, who cared for Cuarón and his siblings in a middle-class neighborhood of Mexico City in the 1960s and early 1970s. “Watching ‘Roma,’” Brody complains, “one awaits…illuminating details about Cleo’s life outside her employer’s family…and [outside] a generously forthcoming and personal relationship between Cleo and the children in her care.” 2 Brody continues, “There is nothing of this sort in the movie; Cleo hardly speaks more than a sentence or two at a time and says nothing at all about life in her village, her childhood, her family.... Cleo remains a cipher; her interests and experiences—her inner life—remain inaccessible to Cuarón. He not only fails to imagine who the character of Cleo is but fails to include the specifics of who Libo was for him when he was a child.” 3 For Brody, Cuarón’s failure to individualize and contextualize has deprived Cleo of a voice; her character is just another example of the hagiographic mode favored by well-intentioned “upper-middle-class and intellectual filmmakers” when they turn their attention to the working poor. 4 Cuarón, in other words, has made the mistake of trying to represent the “Other” and, moreover, he has rendered her as no more individuated than a stereotype. This kind of criticism is familiar enough. The subaltern must speak—preferably for herself, and in her own voice.

When Brody says there is a voice missing in Roma, he is playing on two senses of voice. There is the fact that Cleo has only a few lines of dialogue: she literally does not say much. But there is also a more metaphoric sense of “filmic voice,” what scholars call narrative point of view—an “intangible, moiré-like pattern formed by the unique interaction of all a film’s codes.” 5 For Brody, and for others, Cleo’s point of view has not been incorporated into the film’s narrative point of view.

One of the elementary lessons of film analysis is that one must be careful not to collapse these two senses of voice; it is possible (and not uncommon) for a film’s narration to undermine, rather than amplify, a particular character’s explicit speech. (Think of Citizen Kane, where it is clear that the film’s narration—its filmic voice—comments critically, through a complex flashback structure, on the character of Kane.) But it is perhaps more frequently the case that filmic voice coincides with the perspective of a particular character. The implication of Brody’s title is that Cleo’s literal silence is a symptom of (and a contributor to) a filmic voice that is not only not hers, but also largely indifferent to her point of view.

But what would the film be like if Cleo’s point of view were not missing from Roma’s filmic voice? What would make Cleo seem like a person and not a cipher? This, of course, brings us to the specific formal problems of rendering character subjectivity on film. But notice that built into Brody’s account is an implicit view of what makes a person seem like a person and not a stereotype: some combination of a past (e.g., information about her “life in her village, her childhood, her family”), a voice (e.g., “more than a sentence or two at a time,”), signs of inner life (e.g.,“her interests and experiences”), leisure time that is actually free and in which one can be seen to make autonomous decisions (e.g., “illuminating details about Cleo’s life outside her employers family”). Translated into the terms of film form, we might say that Brody takes issue with the film’s narrative, which eschews details about Cleo’s past and family; with the script, which gives Cleo few lines of dialogue; with the lack of a voice-over narration or flashbacks or memory images; with the casting and/or direction of the main actor, which has opted for inscrutability. We might add that those filmic techniques often used to suggest character subjectivity—eyeline matches, optical point of view shots, sound perspective, close-up reaction shots, shot-reverse-shot structures—are also largely absent from the film.

Brody’s review was met with indignation. Commentators have taken issue with Brody’s suggestion that the film is not attuned to Cleo’s point of view; after all, she “appears in almost every scene, far more often than Paco, the son who appears to be a fictionalization of Cuarón’s younger self,” as Caleb Crain suggests in The New York Review of Books. 6 Many critics have claimed that Cleo does speak, for example, in the scene after the fire when she mentions the smells and landscapes of her village. Some have tried to cleave apart the two senses of voice—maybe she does not say much, but as one film scholar wrote on Twitter, “Probably Hollywood has trained film critics to expect feisty, picturesque, salmahayesque maids to the point that Godard experts can’t see words in silence, and deal with reflexive, stoic portrayals. Cleo has so much voice…if we could only listen.” 7 In this vein, critics have praised Aparicio’s performance, detailing all the ways her restrained, quiet acting style has communicated reservoirs of deep feeling, etc. Michael Wood, writing in the London Review of Books, says “Yalitza Aparicio underacts so wonderfully, does so little with words, that we almost always know what her character is feeling: when she is contented, entertained, worried, frightened.” 8 Dolores Tierney has protested against the stubborn coloniality of “Northern-based, generally (but not always) white/Anglo male film critics” that don’t understand that they don’t understand what they are looking at. 9 As one of Brody’s Twitter detractors put it, summing up a definite thread in the complaints: “What am I saying? I guess the following: this is a cantankerous review written by a gringo.”

What is striking about the criticisms that have been made of Brody’s review is that they largely mirror his own concerns. 10 Like Brody, they are critical of the arrogance of speaking for (an)other that enjoys less power than the speaker. Above all, the subaltern must speak. What is taken for granted is that to represent domestic service appropriately—progressively—one must “give voice” to the domestic by giving density and expressiveness to her character. It is not enough for Cleo to be restored to the frame, so to speak; her inner life must be revealed. Thus what the commentators disagree about is whether Cuarón has succeeded in “giving voice” despite Cleo’s silence. For most, an intentional, calculated refusal of Cleo’s interiority would indeed be troublesome politically.

We can, then, recast Brody’s own criticisms of the film. His concern is not that Roma has tried to represent Cleo’s subjectivity and failed to be convincing (that is one kind of error), but that it failed so much as to even try. For Brody, the fact that the film does not explore Cleo’s subjectivity does not reflect a deliberate choice made by Cuarón; rather, it reflects a blind spot on his part—a blind spot typical of “upper-middle-class and intellectual filmmakers” who attempt to represent the working poor. Moreover, what Brody wishes for is that an authentic, politically-engaged cinema would resolve the ills of the world in representation. If the figure of the servant has been treated in life (and in older representations) as a “non-person,” as Erving Goffman has written, then her personhood must be restored in representation in order to re-animate her. 11

Brody is not alone in his wish for a kind of solutionism on screen. Roma is part of a cycle of more than 25 Latin American art films about domestic service produced over the last twenty years. Many of the films within this cycle are well-intentioned advocacy films that try to recuperate the figure of the domestic by giving her “voice,” in Brody’s two senses. Some feature interviews with domestics in which they describe their lives (e.g., Paulina [Vicki Funari, Mexico/Canada/United States, 1998], Empleadas y patrones [Abner Benaim, Panama/Argentina, 2010], Doméstica [Gabriel Mascaro, Brazil, 2012]). Others explore the domain of leisure time (e.g., Domésticas [Fernando Meirelles, Nando Olival, Brazil, 2001], La novia del desierto [Cecilia Atán and Valeria Pivato, Argentina/Chile, 2017]). Still others embrace consumer agency, showing the maids regain their “freedom” when they act as consumer citizens, making lifestyle choices through their spending patterns in films like La Nana (Sebastián Silva, Chile/Mexico, 2009), Cama-adentro (Jorge Gaggero, Argentina/Spain, 2004], and Play (Alicia Scherson, Chile, 2005).

But this is not the only strategy, even for politically oriented filmmakers. Indeed, the great majority of the films in this cycle—and Roma is just the one that has garnered the most attention—suggest a more controversial understanding of domestic service as an institution that compromises the self on the job, that blocks a certain kind of voicing, that gnarls those that earn their living from it. These are films like Santiago (João Moreira Salles, Brazil, 2007), Parque vía (Enrique Rivero, Mexico, 2008), or Batalla en el cielo (Carlos Reygadas, Mexico, 2005) that catalogue the way the institution wreaks havoc on the personalities of its maid-victims, the way it ruins them—not just the trajectory of their lives, but their selves. These diagnostic films have to navigate tricky terrain. If the democratic ideal embraces “giving voice,” the institution of domestic service—in these films—renders that ideal unstable. Thus, to “give voice” in representation would be to falsify the nature of the institution of domestic service. So, far from being a symptom of Cuarón’s blind spot, Cleo’s inscrutability, her silence, might be read as a calculated choice in the service of a different kind of intervention in politically fraught terrain. This is the line of thought that I want to explore in this essay.

In what follows I will situate Roma within the cycle of Latin American domestic service films before I concentrate on the question of voicing and point of view as a formal as well as political problem in the film. I will try to show that a consideration of the operations of point of view in the film shed new light on both Cuarón’s project, but also on what I consider to be the crux of the matter across this cycle of films—namely, the emotional entanglement of the domestic herself.

The Domestic Service Film Cycle

One of the difficulties that critics have had in thinking about Roma is only passing familiarity with its generic context. 12 This cycle of films is concerned with paid domestic service as an institution. In this respect, these films differ from a previous generation of Latin American popular culture featuring maids; those works were often characterized by interclass romances and allegorical fictions. 13 Unlike the film and media of the past, the domestic workers of this recent cycle are not involved in so-called “foundational fictions,” stitching the nation together through the mechanism of marriage plots between brown maids and their white employers. Nor are they popular melodramas featuring saintly domestics whose virtue goes unrecognized by malevolent mistresses. Films in the contemporary cycle eschew moralistic frameworks. They often feature relatively liberal, warm, well-intentioned employers. The interest of these films is not in their treatment of the politics of exploitation, but rather, in what has been called the “affects of domination”—that is, the affective dimensions of unequal intimate relationships. 14

Even before Roma, the international critical reception of these films has been very positive, and critics have not hesitated to compare them to their European art film counterparts from a previous generation. 15 Reviews are replete with references to Buñuel, Chabrol, Losey. Scott Foundas, writing in The Village Voice, symptomatically observes that La nana (Sebastián Silva, 2008) is “The Remains of the Day as reimagined by a budding Luis Buñuel.” 16

But this assessment of the cycle does not seem quite right. The paradigmatic European art films about domestic service—Joseph Losey’s The Servant (U.K., 1963), Luis Buñuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid (France/Italy, 1964), Claude Chabrol’s La Cérémonie (France/Germany, 1995), and so on—are absorbed by the sadism of the master-servant relationship. There is no glimmer of affection or reciprocity or genuine intimacy; there is only putrefaction, deception, mutual destruction. The servants may be depraved—twisted by this servitude—but they do not suffer from a lack of class-consciousness; they understand very well the realities of the master-servant power dynamic. By contrast, the Latin American films in this archive are interested in a rarely-noted paradox of domestic service: that such an exploitative form of work can produce such a fierce identification of the servant with the employer. 17

This recent interest in paid domestic service among Latin America’s most accomplished auteurs may be due to a historical phenomenon. In the last few decades, the institution of domestic service has changed in Latin America. It is not that it has become less common. People are still hiring others to clean, cook, nanny, chauffeur, garden, etc. Recently, in 2010, paid domestic service constituted about 5.5% of total urban employment in Latin America, down only .5% from the 1990s. In Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Panama it was recently estimated that between 15% and 18% of working women are employed in domestic service; in Uruguay and Paraguay, 20%. 18 Yet if the amount of domestic service has not changed much since the 1990s, its character as labor has.

Traditionally, domestic service was distinguished from other forms of labor by four main characteristics. First, the servant lived in the master’s home. Her privacy and thereby her personal freedom were delimited by the arrangement. Second, the number of hours she worked was often unspecified; she was, in some sense, always on duty. Third, the tasks of most servants were non-specific—they included a variety of jobs from cleaning to cooking to taking care of children. 19 Fourth, the servant would spend a lifetime working for one family; and often her children would become servants to the next generation.

The traditional master-servant relationship—in general and in Latin America, in particular—has long been understood as a “premodern relationship,” a species of pre-capitalist, colonial patron-client relationship. 20 It is for this reason as well that early scholarship on the subject predicted that domestic service would become obsolete as capitalism “matured.” 21 Indeed, traditional paid domestic service presented a paradox. While the occupation is old in human history (i.e., it predates a capitalist mode of production), its dramatic expansion (and feminization)— which has taken place at different times in different places—is relatively new. In most places, it was an indirect consequence of early modernization and industrialization, which introduced a “modern” social inequality that often manifested an equilibrium of labor supply and demand at the bottom and at the top of the income scale. 22 Although it first rose to numerical prominence with industrialization, the character of domestic service retained the stamp of an earlier historical moment. As a phenomenon, a shroud of anachronism has long accompanied it.

The traditional, “premodern” domestic service labor arrangement held in Latin America until relatively recently. 23 The terms of the transformation of servanthood in Latin American would be familiar to anyone paying attention to the broader transformations of work. Servanthood is being contractualized as it gets absorbed by capitalist labor relations and as the state has been pressured to formalize employment in this sector. 24 In practical terms, this means that maids are now increasingly living-out; employment agencies are cropping up to mediate between private households and potential employees; the occupation is becoming more short-term and intermittent; servants work for several families rather than exclusively for one; domestics change jobs more frequently; and tasks are more sharply defined as a stricter division of labor takes hold.

With contractualization comes a transformation in the character of the personal relationship between domestics and their employers. Before, the paternalist character of servanthood, which included intimacy and identification, supported the buttressing ideological fiction that the maid is “a member of the family” or “like a daughter.” 25 Increasingly, that ideological fiction is becoming untenable as domestic workers are becoming more like regular employees. The traditional material inducements for acceding to that paternalist labor arrangement—i.e., the relative security of servant employment—likewise have become precarious. 26

From the point of view of organized Latin American domestic workers—whose unions and employment agencies are having success in pressuring states and employers to formalize, regularize and contractualize a form of work that often depended on the good will of employers—the shift in the character of domestic service, which has mitigated the personalism of the job, has also generally been considered a happy and hard-fought development. 27

These changes have been received more ambivalently by Latin American filmmakers interested in the nature of domestic service. In the face of this historical rupture, the films of the domestic service cycle express a certain, to be sure “politically incorrect,” tension: on the one hand, they are conscious of the politically problematic character of traditional domestic service; on the other hand, they are nostalgic for the cross-class intimacy between masters and servants that traditional domestic service made possible. Indeed, it is worth noting that for several of the films of the domestic service cycle—documentaries like Santiago, Paulina, Empleadas y Patrones, Doméstica and fiction films like Parque vía, Criada, Batalla en el cielo—the servant role is played by the director’s actual servant (or family servant). Even when that is not the case, the character is often based on a real figure from the director’s life (as is the case with Roma). The directors are mostly in their 30s, 40s, 50s; they were growing up with live-in maids in the 70s, 80s and early 90s—and not coincidentally they were also also growing up in the wake of the collapse of revolutionary political projects across the region. The child had a relationship with his nanny/servant; as an adult, one of his first artistic acts is to eulogize her. The domestics in these films are treated with care and consideration; the representations are—to use the language of stereotype analysis—“positive.”

These filmmakers love their domestics. That is not the issue. But what of the domestic’s love? Like a detective story, several films in this cycle sleuth out signs of love. Incredulous and insecure, they seem to ask, “Does/ Did she love me truly?” Indeed, several of the films in this corpus are centered on the question of the domestic’s affective attachment and the existence of a mutually-felt love between master and servant—despite everything. But for cross-class intimacy to be authentic—for her to love me truly—she must be free; she must be a person, she must have an autonomous identity. And that is the problem.

What seems crucial here is the recognition of a new kind of concern. In an earlier historical moment, the domestic’s feigned affect, her good behavior —not her genuine feelings—was all that counted. But once the domestic’s love, emotion, and authentic feeling matter, so too does her personhood. In revisiting the domestic space in which the authoritarian disposition was first learned, internalized, practiced like a ritual, several of these films are engaged in a kind of imaginative do-over. This time, the films try to summon forth the Other. The object of scrutiny is often the domestic’s personhood—her identity, her inner life. Who is she, after all? Who was she? It is in this context that the question of voice and point of view becomes paramount. Different films use different cinematic techniques to capture the domestic’s point of view. One might reasonably suppose that this interest in the personhood of the servant is part of an effort to make visible what was once invisible, to balance a one-sided representational history. To this extent, these films share Richard Brody’s solutionism, his wish for a representation that restores a sense of the domestic as a fully developed person—with a past, varied experience, a rich inner life.

But amid the whole range of films that engage this dynamic, there are alternative (both formal and political) aesthetic proposals. In some films in the cycle—films similarly attuned to the question of the domestic’s affective attachment—the alternative approach is specifically oriented toward a new treatment of point of view. The films I have in mind embrace, in short, a kind of inscrutability of the domestic worker that is tied to a wider suspicion (one that is also familiar to political cinema) about the demands of representation. Roma is an exemplary and instructive case among these, not least because the polemics surrounding it have brought to the foreground the problem of the domestic’s point of view as a problem of film form. 28

Roma

The question of point of view comes up repeatedly in the reviews and commentaries on Roma. 29 Defenders of Roma have tried to claim that Cleo is speaking in Roma, just not in words, and that the film communicates her point of view. Carla Marcantonio writes that “Roma is almost entirely structured around Cleo’s point of view and her experiences; this is the central aesthetic and narrative paradigm that drives the film.” She goes on: “I therefore have a hard time accepting the view that it silences Cleo, despite her silent demeanor.” 30 Pedro Ángel Palou affirms, “Everything in the movie is seen through Cleo’s eyes, not those of the family, not even those of Pepe—Cuarón’s alter ego—, and it is her gaze that makes Roma so compelling.” 31 Sergio de la Mora, striking a more ambivalent note, claims that the camera “shifts between objective and subjective points of view…. A number of sequences are shot through her point of view in a film with few subjective shots. It is never a question of who is mostly doing the looking and telling: it is Cuarón, looking back in time, remembering.” 32 But this quickly gets into deep water. Is the film shot from Cleo’s point of view? Or from Cuarón’s? Is a film being shot from someone’s point of view to be understood as the same as a film structured around someone’s experience? How can a film be shot from a character’s point of view without subjective shots?

I think these ambiguous and contradictory ways of talking about point of view suggest that there is something confusing about the basic conceit of Roma itself. The confusion has to do with the way Cleo’s visibility—her ubiquitous presence in the frame—is combined with the opacity of her character. 33 It seems clear that Cleo is the subject of Roma; she is present in almost every shot, and in some sense, she serves to anchor us within the world of the film. But, despite this centrality, there are very few shots that mimic her visual perception. 34 This eschewal of the point of view shot is amplified by the way the film goes to some lengths to refuse a familiar kind of formal structure that confers the authority of point of view (even if it does not mimic optical or sonic perception): the eyeline match. We see characters, especially Cleo, look in a direction—at something—but these shots are not followed by the reverse shot that would reveal what they are looking at. There are places in the film where one might expect to see reaction shots or a shot/reverse shot structure—but the film has scrupulously avoided them. For example, when Cleo first visits the obstetrician, Dr. Margarita Velez (Zarela Lizbeth Chinolla Arellano), the camera is trained on Cleo for 53 seconds as she answers the doctor’s off-screen questions about her sexual history. Yet, there is not a single shot of the doctor. Or, when Cleo’s baby is delivered dead, the camera position remains fixed (in a medium shot), perpendicular to the prone Cleo: there are no eyeline matches to what the obstetrician or pediatrician see and no optical point of view shots from Cleo’s perspective. 35 The camera’s mode—especially when Cleo appears in long shot—is largely distant, observational, omniscient. In a certain sense, I think the camera is surveillant.

Thomas Y. Levin coined the term “surveillant narration” to refer to the anxiety-inducing, unsettling quality—the “panoptic undecidability”—generated by “unusually long and static shots seemingly lacking in any diegetically attributable point of view,” shots that lack the “eventhood” that the spectator has come to expect from long duration shots. 36 Levin aims to distinguish “surveillant narration” from what he calls classic “ciné-surveillance,” which often signals its genesis in surveillance technology within the diegesis through the use of grainy, black and white footage associated with videotape; high-angles and fish-eye perspective; the “mechanical back-and-forth pan of the CCTV frame”; and/or the use of multiple screens. 37 Because “surveillant narration” is broader, more encompassing, and more undecidable than ciné-surveillance, its boundaries with omniscient narration can be fuzzy. For my purposes here, it is relevant that Levin traces “surveillant narration” back to its ur-instance in the 1895 Lumière films of workers leaving the Lumière factory, in which we have “the gaze of the boss/owner observing his workers as they leave the factory.” 38 Indeed, he argues that “employee surveillance plays a key role in the very birth of the medium.” 39

The approximately five-minute opening shot of Roma may at first seem to belong to this tradition of surveillant narration. As the camera tilts up from a close bird’s eye view of a porte-cochère’s stone floor tiles, it reveals, at quite a distance, the lone domestic, Cleo, coiling up the hose, collecting the bucket and mop, and making her way toward the back end of the porte-cochère. The stationary camera pans 180 degrees, following Cleo as she walks toward it, passes it, and heads to the bathroom off the courtyard before entering the house. The camera’s angle is straight; its height neither high nor low; its location appears to be in the middle of the patio (i.e., there are no signs of a voyeuristic camera, concealed from Cleo’s view). This is certainly not a case of ciné-surveillance; and yet, the shot feels not only unsettling but surveillant. When Cleo enters the bathroom, the shot might have been over with the action—after all, the camera has been following Cleo’s actions and Cleo had just finished cleaning the driveway and courtyard and left the image. But, instead, the camera—stationary and distant—remains trained on the closed door through which she passed for another 30 seconds, waiting for her to emerge; the “eventhood” of the shot suddenly is cast into doubt. (Figure 1)

FIGURE 1. Surveillant narration. Cleo has entered the bathroom and the shot lingers, fixed and static. Frame enlargement. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, Mexico/United States, 2018)

But

if the film’s opening shots engender the impression that Cleo is being

watched as she completes her daily tasks, our sense of who is watching

shifts over the course of the film’s first 20 minutes. What seemed like

an externalization of the employer’s surveillant gaze seems more and

more like an externalization of the servant’s. The beginning of the film

directed the spectator to watch Cleo; she is in almost every shot; she

is the main character, the film suggests, and we are watching her daily

routine from morning to night. This cueing of spectatorial attention is

challenged on the evening of the first day when the family patriarch

returns early from work.

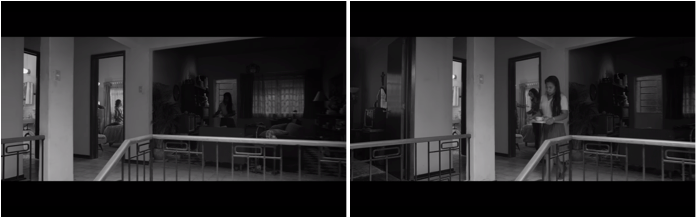

The surveillant narration gives way to a series of quick shots—about 33 shots over 1:20—dramatizing the difficulty of fitting the car into the porte-cochère’s narrow space. 40 The patriarch, Sr. Antonio (Fernando Grediaga), must maneuver carefully in order not to damage the car: the mostly close-up shots alternate between the inside of the car (as he drives forward a few feet, reverses, repositions the steering wheel, taps the ash of his cigarette in the ashtray, and proceeds forward) and the outside of the car—its back bumper, its front bumper, its tires rolling over dog shit, its side mirror scraping the wall. Interspersed across this drama are a few medium shots of a photogenic family scene, illuminated by the car’s headlights: mother (Sra. Sofía), children (Sofi and Pepe), and, behind them, Cleo (holding back the dog). All—with expressions of delight and expectation—are eagerly waiting the father’s imminent emergence from the car. (See Figure 4A)

There is something almost iconic about this image of bourgeois family stability and contentedness. Sr. Antonio gets out of the car. The family greets him excitedly, the children peppering him with questions. They open the door to enter the house, but just as one expects a cut to take us across the doorway’s threshold into the house where the drama continues, the surveillant narration is restored. The door closes. The family is inside. The voices of the children trail off. And there is Cleo still holding back the dog. All that drama and then the crowding of the frame induced us to forget momentarily that Cleo was there the entire time, holding back the dog so that Sr. Antonio could park the car and so that the mother and children could live out this picture-perfect domestic scene. In the last few seconds of the shot, the image returns us to Cleo, insisting on her presence.

The point I wish to emphasize here is not merely that this family life is made possible by domestic service (though that is certainly true). This scene—bookended as it is by the surveillant narration that characterized the beginning of the film—begins to reframe the subject and object of the surveillance gaze: the new object is the relation between the family and the domestic, and the subject of that look is the domestic. For when the door closes leaving only Cleo in the shot, our frustrated expectation invites a thought about Cleo: What must it have been like to hold back the dog for the long process of car-parking? What must it have been like to be part of the family portrait one moment and then to have the door unceremoniously shut in one’s face? And how could the family do this?

A servant is the paradigm of what Erving Goffman called a non-person. She is a figure for whom “no impression need be maintained.” 41 As an example, Goffman turns to “Mrs. Trollope” writing about masters’ “habitual indifference to the presence of their slaves. They [the masters] talk of them, of their condition, of their faculties, of their conduct, exactly as if they were incapable of hearing.” Mrs. Trollope goes on, “I once saw a young lady, who, when seated at table between a male and a female, was induced by her modesty to intrude on the chair of her female neighbour to avoid the indelicacy of touching the elbow of a man. I once saw this very young lady lacing her stays with the most perfect composure before a Negro footman.” 42 Goffman’s insight has surely inspired a number of cocktail and dinner party sequences across the history of cinema in which the partygoers talk about “the help” right in front of it.

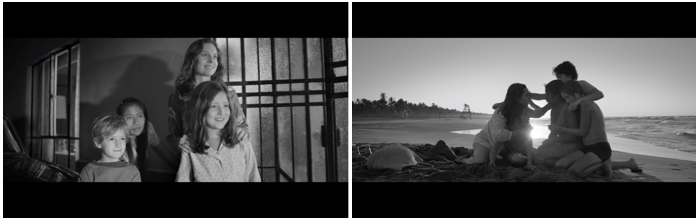

Early on in Roma there is a scene of this type. It is bedtime and the family is upstairs, each member in her/his own room. The rooms are on the second floor, oriented in a semi-circle, each one facing a balcony looking onto the first floor. A deep focus long shot simultaneously pans and tracks, from some space beyond the balcony, moving from right to left about 90 degrees and less than five feet. The crane shot surveys Cleo as she leaves Sofi’s (Daniela Demesa) room after tucking her in; as she passes the kids’ bathroom; then as she moves past Toño’s (Diego Cortina Autrey) room where an open door allows us to see him bouncing on his bed playing with a football. Cleo calls out to him, chiding him: “Toño, go to sleep.” She proceeds to the family room where she turns out two lights and picks up the tea cup and saucer she had delivered to the patriarch earlier in the evening.

This shot bears some resemblance to an earlier shot in the film. (Figure 2A-B) Set in the morning of the same day, this earlier shot surveys the same spaces from the same camera position at about the same distance. The shot makes an arc from left to right and back again as Cleo makes beds, returns toys to their rightful rooms, collects the dirty linens and clothes, etc. The point of the later shot’s formal repetition of this earlier one is not subtle: Cleo has been working all day long.

FIGURE 2 A-B. Morning and night, same camera set-up. Cleo cleaning up in the morning (left, 2A). Cleo putting the children to sleep in the night (right, 2B). Frame enlargements. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, Mexico/United States, 2018)

In the evening’s reprise of the earlier scene, the sounds Toño is making in imitation of a real football game mingle with and eventually recede as a conversation that Sra. Sofía (Marina de Tavira) and Sr. Antonio are having in their own room, which shares a wall with the family room, becomes audible. The frame is now split between the darkened family room where Cleo has picked up the dirty dishes and is making her way to the stairs, and the couple’s bedroom where, through the open door, we can see Sra. Sofía sitting on the edge of the bed. (Figure 3A) Sr. Antonio is complaining, largely about things having to do with Cleo: where is his brown tie; the house is a mess; the fridge is full of empty cartons; when he got out of the car he stepped in dog shit; etc. As we hear his litany of complaints (the camera is much further from him than Cleo is, as we are beyond the balcony), Cleo maintains her position in the center of the frame. It is a centralized position that again makes us ask questions: Did she hear all this? What must she be thinking about it? Is she angry? Disgusted? As Cleo makes her way to the landing, stepping into the light a few feet away from the couple’s bedroom, Sra. Sofía closes the door. Cleo is expressionless. She does not even blink. (Figure 3B)

FIGURE 3 A-B. Cleo cleaning up while Antonio complains about her work within her earshot (left, 3A). Cleo, does not react (right, 3B). Frame enlargements. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, Mexico/United States, 2018)

Imagine how different the effect of the sequence would have been if the camera had actually entered Sra. Sofía’s bedroom, if the couple’s conversation had been shot using the convention of shot/reverse shot? If a shot/reverse shot pattern had been employed, each shot would have been pegged to a specific, individualized reaction—either of Sra. Sofía or of Sr. Antonio. Surely, we would have similarly concluded that Sr. Antonio is an asshole, that Cleo works very hard, that everything she does to reproduce the family’s comfortable life from day to day is lost on this dull, vacuous shell of a man. But the invitation to judge Sr. Antonio is not the core work of the actual sequence. Rather than tracking an interplay of different faces and reactions, we are made to watch Cleo as she hears Sr. Antonio’s words. We listen as Sr. Antonio speaks loudly in a room with an open door probably knowing that Cleo is at that very moment on the same floor putting his children to bed. He is not concerned about her judgement of him, or the impression he is making on her. But we are thinking about what impression he is making on Cleo, and we are scanning the image for signs of her subjectivity. Does she cry? Does she grimace? Does she frown? Does she blink? In the almost total absence of expressiveness, we are left wondering, asking, “how does this scene look to the domestic?”

This question recurs throughout Roma. The film’s overall narrational mode may indeed be surveillant, but Roma will adopt a kind of sousveillant narration (which is probably cemented at precisely this point in the film). That is, rather than a boss’s gaze surveilling the domestic at work, the film substitutes a domestic’s gaze, a surveillance from below. This sousveillant narration means that across the film the spectator is asked to judge not so much individual characters as the scene itself: the spectator is prompted to scrutinize a social relation. There is something very satisfying about the moral clarity of the scene in which the spoiled Sr. Antonio complains about Cleo with not the faintest awareness of all the labor that makes his existence possible and that he takes for granted. There is melodrama here—melodrama and the concomitant pleasure of a perspicuous moral culpability. See! Look how they mistreat her. Ungrateful parasites. Or, consider the scene in which Cleo looks on helplessly as Paco (Carlos Peralta) listens through the bathroom door as his mother discusses his father’s abandonment. When Sra. Sofía emerges from the bathroom to find Paco eavesdropping and Cleo in the background, she explodes: “And you? Why did you let him [eavesdrop]? Fuck.” The image cuts to a three-quarter shot of the pregnant Cleo, stunned. Sra. Sofía barks a follow-up: “Why are you still standing there? Don’t you have anything to do? Get out of here!” And then we can think: See, typical. What a rotten mistress Sra. Sofía is!

The viewer waits for sequences like this. And Roma occasionally indulges this desire. But much more common is the scene in which Cleo asks to speak with Sra. Sofía about her pregnancy. We are braced (and in a certain sense hoping) for Sra. Sofía to be callous: would she forget that Cleo had asked to speak to her only moments before? Would she be distracted and indifferent as Cleo struggles get out the news? Would Sra. Sofía become enraged? Would she fire Cleo on the spot? But Sra. Sofía isn’t callous. And the presence of that dynamic, that relation, makes things difficult for the viewer.

Indeed, the film is full of scenes depicting the relation between Cleo and the family that are difficult to judge. The film’s climactic one-shot, 5:20 scene on the beach, the one that has provided the iconic image for publicity materials, is one of these. 43 (Figure 4B) The sun is setting on an empty beach. Sra. Sofía has gone with her son, Toño, to check the tires on the car for the ride back to Mexico City. She has left clear instructions: Paco and Sofi are allowed to play along the shoreline, but they are forbidden from entering the ocean as Cleo cannot swim and would not be able to save them if something were to go wrong. The children immediately disobey their mother’s command; they enter the ocean. Cleo calls out to them to return to the shoreline—their mother said so, Cleo reminds them, or else they will have to get out altogether. Predictably, they disregard her entreaty. Cleo becomes concerned and the camera tracks along with her as she enters the ocean to try to rescue the children. Because she remains in the center of the frame throughout, the children are off-screen at first as Cleo goes further and further, deeper and deeper—she is alone in the frame and pummeled by the waves. Will she die alone trying to save these children? The thought crosses one’s mind. (Here the fantasies of melodrama lurk: the potential tragedy of Cleo’s unrecognized virtue.) But Cleo manages to reach the children and bring them back to the shore where they all three drop to the sand in an embrace. Soon Sra. Sofía, Toño, and Pepe (Marco Graf) join the tableau. Sra. Sofía thanks Cleo, and then there is a misunderstanding. Cleo says she didn’t want her, referring to her daughter who was stillborn. Sra. Sofía thinks she is referring to her own children and reassures Cleo, “They’re okay.” Cleo clarifies: “I didn’t want her to be born.” Finally getting it, Sra. Sofía replies, “We love you so much, Cleo. Right?” “Poor thing,” says Cleo, still on a different track. The children agree with their mother. Sra. Sofía says it a few more times.

FIGURE 3 A-B. Portrait of a family awaiting the arrival of the patriarch (left, 4A). Reconstituted family (right, 4B). Frame enlargements. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, Mexico/United States, 2018)

If this sequence might—in a first pass—invite one to adopt a melodramatic frame to analyze it, the sequence becomes less straightforward if we filter it through a sousveillant perspective. Sra. Sofía surely knew that the children would pay no attention to Cleo, for while Cleo provides the care and comfort of a mother, she lacks the mother’s authority. And so, Sra. Sofía might be said to have put Cleo in an impossible position. This suggests a certain failure of consideration. That failure is alluded to again when Sra. Sofía thinks that Cleo is referring to her children, Paco and little Sofi, rather than to Cleo’s own baby when she says she didn’t want her. We see that Sra. Sofía cannot really see Cleo, that she cannot imagine how things might look to her, or what might constitute Cleo’s main spheres of concern. And yet, once Sra. Sofía has understood that Cleo is talking about her own stillborn baby, she responds plausibly, humanly, as if to say, “you are not alone; you have us; we are your family.” From what we know, this is not exactly false: Cleo is separated from her family and dependent on this one—for money, surely. But the film’s sousveillant narration raises the question of whether Cleo depends on the family for the sorts of things that money cannot buy—and perhaps more crucially, whether Cleo reciprocates their affection. The visual tableau is, in effect, a portrait of a reconstituted family—a redo of the earlier shot in which the family waited expectantly while Sr. Antonio parked the car. (See Figure 4) In the sequence that I have been describing Cleo does not acknowledge Sra. Sofía’s profession of love. Faced with this fact, one wonders—though without being given material to formulate an answer—how the scene looks and feels to Cleo. Does she feel unseen? Does she feel taken advantage of/exploited? Does she feel that she is part of the family? Does she feel loved by them? Does she love them? What is unbearable, maybe unspeakable, in this climactic moment of the film is the possibility of an entanglement between Cleo and the employer’s family that is, at once, devastating for Cleo’s autonomy while at the same time full of a real and sincere reciprocal affection.

I emphasize “possibility” here because while the film’s sousveillant narration may raise questions, it gives no definite sense of Cleo’s subjectivity. Her character does, as critics have said, remain opaque. Without subjective or reaction shots, and with Aparicio’s cultivation of an impassive facial expression in her performance, Cleo’s inner life is off-limits. Yet this refusal of interiority is, I would venture, not an oversight, but rather one of the film’s guiding principles.

If we look for it, opacity can be recognized as a visual motif threaded throughout the film all the way back to the opening aerial image of Roma in which the stone tiles of the open-air porte-cochère are being washed with successive waves of soapy water. 44 (Figure 5) The first shot of the geometrical pattern of the porte-cochère’s patio reveals a palpable sense of the texture and color gradations of the hardy tiles. But when the first bucket-full of water has settled on the patio surface, a different image overlays the first, entirely obscuring the patio’s tiles. The water’s reflective properties and the darkness of the tiles underneath now reveal a white rectangular frame in the center of the image. It is the sky directly above that we see reflected in the water; soon we will see a plane flying across the reflection of the sky. The shot as a whole is something of a palimpsest; it has two layers. Each time a new wave of water is introduced, the bottom layer becomes momentarily visible until the water resettles. What is off-screen, in the space behind the camera, finds expression in the on-screen image as a consequence of the reflective qualities of water—and in later shots of glass.

Again, this is not a unique visual trope. In the middle of the film, Cleo is gazing through a glass window at a nursery of newborns resting in incubators. (Figure 6A) Eventually there is a medium shot of Cleo, taken from inside the nursery. Her face is pressed up against the window, but the image is obscured as the window’s glass is catching the light from behind the camera and reflecting, superimposing—on Cleo face, on the window’s glass—the objects and people that belong to the nursery and that are off-screen: the incubators, heat lamps, a nurse. The shots make it difficult to see what belongs to the space in front of the camera and what belongs to the off-screen space behind it, and seeing clearly through the window at Cleo is impossible as her face and her dark clothes become especially useful conduits for reflecting what is behind.

FIGURE 5. From the opening credits: water, both transparent and reflective. Frame enlargement. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, Mexico/United States, 2018)

FIGURE 6 A-B. Cleo looking into the nursery (left, 6A). Cleo looking outside the car window on the way back from the beach (right, 6B). Windows: both transparent and reflective of off-screen space. Frame enlargement. Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, Mexico/United States, 2018)

Toward the end of the film, after the climax, when Cleo has saved the children from drowning in the ocean, Sra. Sofía, Cleo, and the four children are in the car returning to the city from their countryside vacation. Sra. Sofía is driving. In a series of medium shots, the camera, perched outside the car, surveys its passengers through the car’s windows. The first of these, 12 seconds long, focuses on Sra. Sofía, filming her through the front windshield. But the glass is pitched upwards in such a way that it catches the light from the sky, reflecting fuzzily the surrounding landscape—the trees and bushes and clouds, which are superimposed, mingle indiscernibly with her image. The next shot, seven seconds long, is of Toño in the passenger seat with his head resting against the window; he has a furrowed expression and looks out of the car window blankly—the car’s other passengers, all quiet, clearly visible in the background. The third shot, also 12 seconds, is taken from outside the back window where Paco stares out at the landscape behind the camera. As the car moves along the road, the passing environs fleetingly flash on the window’s screen. The last shot, 30 seconds long, looks through the rear passenger window at Cleo, looking forward, holding a sleeping Pepe and a sleepy young Sofi, who declares “I love you very much, Cleo,” as she rests her head on Cleo’s shoulder. (Figure 6B) Cleo replies, “I love you very much too, my child,” taking Sofi’s head in the crook of her arm. Then Cleo turns her head slightly to look out of the car window, just to the right of the camera. As she stares out at the desert landscape for another 20 seconds (!), an especially big cloud-strewn sky worthy of Emilio Fernández’s golden age films plays on her face, obscuring it from view. (Tellingly, this shot from the film has also become iconic; many a review and commentary feature a frame enlargement from it.)

In

these last two examples, the glass “screen” on which the off-screen

space is projected is an imperfect surface as it is both reflective and

transparent. We can see through

it to Cleo’s face (or Sofía’s or Paco’s or Pepe’s, etc.), but not

clearly; the image(s) behind the glass are in a sense filtered through

the scene behind the camera in a superimposition reminiscent of Maya

Deren and Alexander Hammid’s iconic image from the experimental Meshes of the Afternoon (United

States, 1943), a film concerned precisely with a woman’s interiority

and the difficulty (and promise) of accessing it from the outside

(whether by another person

or by the film’s spectators). (Figure 7)

FIGURE 7. Iconic image from Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, United States, 1943). Why this image has come to stand-in (almost like a synecdoche) for the whole of a film about a woman’s subconscious—a film that P.A. Sitney has referred to as a psycho-drama—is a suggestive question. While the image captures, visually, the imprint of the outside world, superimposing it on Deren’s figure, it is a quintessentially mysterious image—one that suggests the impenetrability of the other.

Indeed, Cleo’s obscured interiority is metaphorized in this recurrent visual motif. But to what end? In this last example that I have discussed above—in which Cleo assures little Sofi of her love and then looks out the window—one may find oneself wondering not just what Cleo is thinking about (which one may also wonder in all the previous shots), but also whether she means what she has just said, whether she really does love the children she embraces, whether she resents the emotional burden her job has placed on her, whether she misses her home and her family, whether she really didn’t want her daughter, whether she wants to be a mother, whether she ever will be one.

Through these close descriptions, I have been trying to suggest that one of the film’s central achievements is the way it trains the vision of the spectator, rendering it sousveillant. That is: we begin to approach every scene of the film, to judge every scene, from the standpoint of someone in Cleo’s position. This is different from “identifying” with the character Cleo whom we see onscreen. Psychological identification with screen characters is often cultivated by overtly expressive performances and by the employment of point of view camera choices; in Roma, this form of relationality has been largely blocked for us. Indeed, rather than “fusing” with Cleo (or projecting ourselves into her shoes or even sympathizing unconditionally), we are often judging Cleo as well—though not as the employer would, but perhaps as a class-conscious domestic worker would. 45 Moreover, this trick, this sousveillant gaze does not answer questions about Cleo’s interiority so much as it raises them. No doubt the mystery of Cleo’s inner life engenders a certain spectatorial involvement, just as it does in other well-known art films with inscrutable characters (e.g., Robert Bresson’s Mouchette). But unlike other art films, the mystery has a definite focus: it is centered around how someone—in Cleo’s position—feels toward the family that employs her. 46 And notice that this judgement is independent of whether we think Cleo is herself judging her employer, whether we think she actually is offended or hurt or angry with them. (Think back to the sequence where Sr. Antonio is complaining about Cleo within her earshot.) When Sra. Sofía says, on the beach, “We love you so much, Cleo,” or when little Sofi says, in the car, “I love you very much, Cleo,” we believe them, and we judge them. They love Cleo in their blind, inconsiderate or childish kind of way. But, when Cleo answers, “I love you very much too, my child,” we are skeptical, perhaps discomfited. Does she really? How could she? And—more disturbingly—what if she does?

True Love

Roma is by no means the first film to broach the question of whether the employer’s love is requited. 47 An important current in the cycle of Latin American domestic service films has taken this as a central theme. For example, in El niño pez (Lucía Puenzo, Argentina, 2009), the momentum of the film is shaped by the indecipherability of the domestic’s affection. Ailin, the domestic, is the obscure object of everyone’s desire; she is a cipher. Almost every character in the film wants her: her own father, the judge for whom she works, the man she seems to live with, a prison official, a prison guard, and the film’s main character, Lala, the employer’s daughter. But Ailin herself is inscrutable. In fact, the film is organized around the mystery of her desire—whose desire does she actually reciprocate? Only at the very end does it seem that it is her charge—Lala—that she truly loves, but even this remains ambiguous.

We can see another example of this in La ciénaga (Lucrecia Martel, Argentina/France/Spain, 2001). Momi, the employer’s daughter, only “wants” Isabel, one of the family’s servants. She is hopelessly attached, constantly caressing her, sidling up to her, laying her head on Isabel’s shoulder. For her part, Isabel is unreadable, impassive. Is it just a job or does she reciprocate some of Momi’s affection?

FIGURE 8. Marcos, the family driver. From the first shot of Batalla en el cielo (Carlos Reygadas, Mexico, 2005). Frame enlargement.

FIGURE 9A-B. Domestic and the daughter of the family. Last two shots of the film. Frame enlargements. Batalla en el cielo (Carlos Reygadas, Mexico, 2005)

In Carlos Reygadas’s Batalla en el cielo (Carlos Reygadas, Mexico, 2005), the narrative is bookended by a declaration of love in the middle of a blow job. Ana (Anapola Mushkadiz), the young, attractive daughter of an elite family, is fellating Marcos (Marcos Hernández), her family’s driver. The film begins with the camera surveying, in two, objective takes, the impassive, naked, rotund, brown, middle-aged, standing Marcos (played by the Reygadas family’s former driver); the camera moves down from his face to reveal the kneeling Ana fellating him. 48 (Figure 8) The camera moves around Ana’s dreadlocked head to eventually rest on a blurry, extreme close-up of her eyes filled with tears. The close-up is what one might expect as a trigger for a flashback or dream sequence. Is the film that follows, in which Marcos stabs Ana to death before dying himself, his daydream or her masochistic fantasy?

The film ends with the same scene, this time rendered in a series of three point of view shots. The shot/reverse shot structure begins and ends with Marcos’ point of view looking down at Ana fellating him. So, was it his dream? The first high angle medium shot is followed by its dyad—a low-angle medium shot of the smiling Marcos. From off-screen in the last shot of the film—the high angle medium shot of Ana—Marco says “I love you a lot, Ana.” Ana, pauses, lets Marcos’ penis slide out of her mouth long enough so that she can clearly say, “I love you too, Marcos.” (Figure 9A-B)

Somehow the language of love seems incongruous in this visual landscape. The clinical, florescent lighting magnifies Marcos’ imperfections: his sweatiness, his adult acne, his scraggly beard, the scars left by pimples on dark skin, his sloping shoulders and sagging breasts, etc. (See Figure 8) Anapola is saved the indignities of such lighting only by her youth. 49 What can the declaration of love during a non-reciprocal sexual act mean in this context? While the real Marcos—the Reygadas family’s actual sometime employee/driver—endures the camera’s humiliation for the sake of the son of the family for whom he once worked, he is at the same time actually being fellated by an attractive, actually wealthy would-be film actress half his age who has affectionately remarked in interviews that Marcos is a “simple and straight [forward] person” unlike “us”—the “Occidental people [who] have such a big necessity to explain everything detail by detail, giving everything an intellectual and logical perspective.” 50 Why had Marcos Hernández agreed to participate in the film project? Anapola is launching a career, but Marcos? Carlos Reygadas has been eager to explain in interviews that Marcos won’t give them: he does not care about “such things” as money, fame, or—presumably—cinema. Reygadas reported that after two days at Cannes, Marcos was eager to return to his family in Mexico—to barbeque. 51 The upshot of Reygadas’ explanation is unclear. Is the point that Marcos participated in the film for Reygadas—out of authentic feeling, real affection?

In the case of Batalla en el cielo, Marcos (the actor) and Marcos (the character) are both inscrutable; their real feelings a total mystery. Reygadas has blurred the line between film and life, using his actors’ names for his characters and bringing the actual relations of power between Marcos (the actor), Anapola (the actor), and Reygadas (the director) into the calculation. While the love dialogue of the last sequence of the film has Marcos and Ana mutually affirming their love for each other, the blow job and its staging (with Anapola kneeling and Marcos upright) suggests a different power dynamic at work. The camerawork and mise-en-scene which conspire to cast Marcos in a particularly unattractive light suggest still another power dynamic as it is Reygadas (director and former employer) pulling the strings, giving the orders, and Marcos in the position of being directed, of doing what he is told, though neither for money nor fame. The question remains, does Marcos do it because he is still in some way indebted to his former employers the way a vassal is always indebted to his lord? Does it satisfy some part of a compensatory revenge fantasy? (After all, he gets fellated by a rich, young, condescending, white actor.) Or does he do it out of true love?

Love for Sale

In 1975, in one of the few attempts to capture the pscyho-social dynamics of domestic service, the sociologist Lewis Coser wrote of the “strong affectual ties binding servant to master” and of the way the servant “tended consciously and unconsciously to identify with the master and took him as a model to be imitated.” 52 Focused on the “premodern” character of the traditional master-servant relationship, Coser’s account explained the strong affectual ties between servants and masters not as the servants’ moral failing, but as a consequence of structural features of traditional domestic service—living-in, unspecified hours, non-specific tasks. These standard requirements of the job curtailed the servant’s outside ties and bound her to the employer almost completely. The arrangement served the interests of the employer who wished to secure the loyalty of the servant, who knew very well—after all— the master’s secrets. In exchange, the master was bound to care for his servants (even in old age after they were too old to work) as he would care for his family members. “Even though their [the servants] assimilation to a family status, fundamentally at variance with other occupational statuses, tended to ‘infantilize’ servants, they also profited from what were certain Gemeinschaft characteristics that continued to mark the master-servant relations even when the cash nexus and Gesellschaft relations already governed most other occupations.” 53 Without passing judgement on either servant or master (whom Coser believed actually felt duty-bound to treat his servants with kindness), Coser tries to uncover the mechanisms by which “greedy organizations” (like the families that employ servants)—not satisfied “with claiming a segment of the time, commitment, and energy of the servant, as is the case with other occupational arrangements in the modern world”—demand “full-time allegiance” and thus “always attempt…greedily to absorb the personality of the servant.” 54

But what exactly does it mean for a person’s personality to be absorbed? In his essay, Coser marshals the often-quoted lines of Jean Paul Sartre’s commentary on Jean Genet’s The Maids:

[I]n the presence of the Masters, the truth of a domestic is to be a fake domestic and to mask the man he is under a guise of servility; but, in their absence, the man does not manifest himself either, for the truth of the domestic in solitude is to play at being a master. The fact is that when the Master is away on a trip, the valets smoke his cigars, wear his clothes and ape his manners. How could it be otherwise, since the Master convinces the servant that there is no other way to become a man than to be a master. 55

The conundrum described by Sartre is a problem of point of view. The domestic vacillates. On the one hand, the domestic—occupying his independent point of view—secretly rejects the master’s view of him, he fakes his servility and hates his master. But, on the other hand, having internalized the master’s hierarchical worldview, he adopts the master’s stance toward someone such as himself, becoming, thereby, a class traitor. What Sartre describes here is surely a kind of false consciousness on the servant’s part (e.g., the servant comes to think that “there is no other way to become a man than to be a master”). But there is nonetheless something of the domestic’s resistance in the account: the servant deliberately fakes servility and masks his true feelings (e.g., “the truth of a domestic is to be a fake domestic and to mask the man he is under a guise of servility”).

This reading of the Sartre passage is probably familiar. But I think Coser actually leads us to consider the problem differently. What if there is no faking or masking? No hate? Are there some kinds of labor that systematically annihilate even this expression of resistance? This is the unsettling premise of Coser’s work.

The last forty years has seen new research focused on forms of labor—dubbed affective labor—that (re)shape workers’ subjectivity. This research, I would argue, is of a piece with the earlier efforts by scholars like Coser. In the more recent work, old forms of labor—like sex work and domestic service, which existed in non-capitalist social formations—have been examined alongside new forms of affective labor like commercial surrogacy, organ sale, and service and care work. All these kinds of labor have been situated on a continuum: At one end is the service work of flight attendants and fast food workers (i.e., those whose job it is to deliver service with a smile); at the other end of the continuum is prostitution, commercial surrogacy, organ sale. Domestic service belongs to this extreme end of the continuum. 56

This subcategory of affective labor—sex work, commercial surrogacy, organ sale, and care work—has been the subject of intense debate within political and legal theory, focusing largely on the permissible limits of commodification. The key question has been how to think about what spheres of life, if any, should not be commodified. 57 The premise has been that there is an important distinction to be made between renting labor power and selling the self, even if people disagree about where to draw that line. The favorite test case for thinking about this special category of labor where one is at risk of commodifying the self (or alienating what is considered inalienable) is sex work. Adjudicating whether one is renting the body, selling a service, or selling the self requires a firm idea of what belongs to the person, what belongs to the “substance of her being,” to her personality, and what does not. In the case of sex work, those like Elizabeth Anderson have defended the intrinsic degradation of sex work (and reject such commodification of the intimate sphere). They argue that sexual acts should be understood on the model of gift exchange. Moreover, because sexuality, on this view, is seen as integral to the self, selling sexuality is considered a self-estranging activity that devalues the seller, who allows her person to be used instrumentally, as it devalues sexuality as a shared human good. 58

As in sex work (and commercial surrogacy and organ sale), the primary worry about domestic service is a worry about the nature of the commodity being bought and sold. 59 It is generally thought that what is bought and sold in traditional paid domestic service is not labor-power as we conventionally understand it—that is, the capacity to work at a defined task for a contractually agreed upon period of time. In this way of thinking, the domestic worker is not merely renting out his or her body in an analogous way to the automobile factory worker who spends the workday on the assembly line repeating a bodily action. Most scholars maintain that it is personhood itself—or as one put it, “her identity as a person”—that is being sold and that is being purchased in domestic service. 60 This sale of personhood is at the core of the special terribleness of domestic service.

In this view, the servant who identifies with the master and his household, who loves the family back, is at risk of being self-deceived and estranged from her self. Self-deceived in this sense: When she identifies with the master, she imagines herself a member of the family, a friend maybe, and gives the gifts that correspond to the private sphere: loyalty, trust, sympathy, love, affection, etc. But unlike with the gift exchanges that go along with personal relationships where reciprocity dictates reciprocity in-kind, she can have no expectation of reciprocity in-kind. She is expected to “display” care, affection, loyalty—it is her job after all—but her employer is not similarly bound; his display of these “goods” are subject to his whim and there are no risks or penalties if his whim leads him elsewhere. 61

The domestic who loves her master is always at risk of being self-estranged. The work of the domestic servant requires the constant display of loyalty, care, and affection. These displays are part of the job description. Given this, the domestic is faced with two options: 1) she can either fake the emotion that she has to display; or 2) she can make those emotions her own. If you fake it, as many people in the service industry do, you curse the boss in your heart and police your outer expression so your real feelings do not shine through. Arlie Hochschild, writing on the emotional labor of flight attendants, has called this "emotive dissonance"—in other words, the tension between feigned emotion (a happy, loyal attitude toward the employer, say) and sincere feeling within oneself. But emotive dissonance is exhausting, Hochschild maintains; it puts a strain on the individual that she will try to neutralize. The individual neutralizes the strain by bringing outside and inside closer together, either by not feigning (that is, by not surface acting) or by changing what one feels (deep acting). In deep acting, “true” feeling has been colonized, and the individual is self-estranged. 62

For Hochschild, feeling, or emotion, acts as a relay to the self, especially in a historical moment when the sense of a solid, stable, core self eludes us. Thus, emotion has a “signal function”: it keys us to how to respond to a given event. When this “signal function” is distorted by commercialization, we lose touch with what our feelings tell us about ourselves. 63 In effect, to the extent that the emotional labor demanded of the domestic ends up shaping not merely her “face”—i.e., her feigned outward behavior—but her inner feelings as well, to that extent the commodity being purchased in domestic service is the personhood of the domestic, “the substance of her being,” her love. 64 This phenomenon has been considered a kind of emotional false consciousness. 65

But I do not think that reading the domestic’s love simply as a kind of emotional false consciousness settles the matter. Remember in the analogous case of sex work, the concern was twofold: it was a concern about the impact on the seller of selling personhood, but it was also a concern about what happens to the gift value—sexuality—when it is commodified. Consider the case of domestic service. The true feelings generated within this coercive labor relation are no less authentic as a consequence of the conditions of their flowering. As the legal philosopher, Margaret Radin, has said: “Commercial friendship is a contradiction in terms, as is commercial love.” The authentic feeling of the domestic, in contrast to “faking it,” preserves the gift values of friendship and love as noncommodifiable, shared human goods. We might say that colonized feeling—unlike sold sexuality and unlike mere feeling displays—has an impact on the seller, but preserves the gift values of love and care. The domestic’s true love, thus, might also be read as a refusal of commercialized love.

Writing on Virginia Woolf and her servants in Mrs. Woolf and the Servants, Alison Light acknowledges that—as the granddaughter of a live-in domestic—when she first started the book project she “found it hard to think of domestic service except as exploitation, a species of psychological and emotional slavery— ‘dependency.’” 66 And this is the orientation of most of the scholarly literature on domestic service. In the course of writing the book, Light’s husband fell ill with cancer and she tended to him until his death a few months later. When she eventually returned to the book project, her perspective had shifted. She writes controversially: “Dependence was no longer a question of whether, so much as when. And I also came to think that the capacity to entrust one’s life to the care of others, including strangers, and for this to happen safely and in comfort, without abuse, is crucial to any decent community and to any society worth the name.” 67 Light’s revised assessment follows from a consideration of the work of the domestic, which has an aspect of one of the most defining features of human life—namely, our sociality. The work of the domestic—whether taking care of children or of the sick or cleaning-up—is the work of social reproduction, the maintenance of human life. It is not the, perhaps more palatable, socially-prestigious invention and design of consumer goods like flip-top toothpaste, but arguably it is much more significant. Light seems to suggest that the servant’s affection, emotion, care—and its resistance to commercialization—registers the worker’s tacit recognition of the crucially human nature of the work itself.

Coda: The Revolutionary Maid

In one of the great films about class conflict, Sergei Eisenstein’s Strike (1925), there is a comical moment when, having crumpled a piece of paper in which the striking workers had listed their demands and used it as a rag to clean off his shoe, an industrialist imperiously summons the butler to clean up the mess. The butler collects the debris. On his way out of the room, he peeks at the paper. “A nice reply,” he says (in an intertitle)—with an approving laugh—of the crumpling of the paper. With these words, the subaltern (the butler) has spoken. Eisenstein cannot resist; the next intertitle editorializes, confirming the common sense of the age: “Every family has its black sheep.”

There was a time when it was common (and acceptable) to think of the servant as ideologically compromised, situated awkwardly in relation to different social classes. This analysis is more problematic today as the common sense has shifted. We like to think of people—especially ordinary people—as free, autonomous, self-possessed, and not as self-deceived or mistaken in their perceptions or analyses.

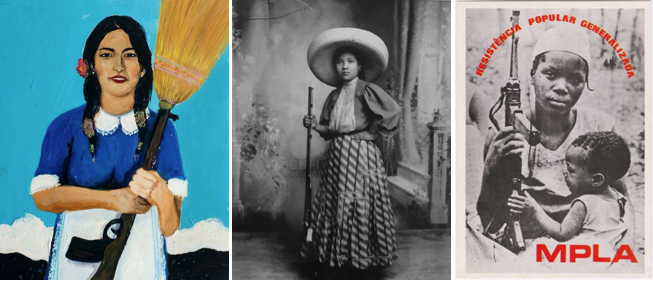

Indeed, the spirit of the present is crystallized in an image that is perhaps the inverse of Eisenstein’s laughing butler. (See Figure 10A) Made by “Papas Fritas,” a Chilean artist-activist, the image depicts the French/Chilean hip hop artist, Ana Tijoux, dressed in a maid’s uniform holding a broom/machine gun contraption. The picture was inspired by an episode that took place in March 2014 at a Lollapalooza festival. Tijoux was interrupted during her set when someone in the crowd yelled out: “cara de nana [Maid Face],” as a way to tie Tijoux’s mestiza looks with the “lowliest” of jobs. Tijoux finished the set. Later she tweeted: “Para los que lo creen insultarme llamandome cara de nana tremendo orgullo por todas las mujeres trabajadoras ejemplo de valor! [To those who think they can insult me by calling me ‘maid face’[:] tremendous pride in all those working women—examples of valor].” The episode caused a stir on social media and on the Chilean talk shows. Three months later, on Facebook, Tijoux posted the Papas Fritas image. Referencing the iconic imagery of the “soldaderas” of the Mexican Revolution and of 1960s Third Worldism, the painting casts the figure of the maid as an armed revolutionary. (Figure 10A-C)

FIGURE figure 10a-c. “Papas Fritas” image of Ana Tijoux as a maid-revolutionary (left, 10A). “Soldadera” of the Mexican Revolution, photographed by Romualdo García, ca. 1910 (center, 10B). Poster for the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) (right, 10C).

Let us turn back to the analysis of the films in the Latin American domestic service cycle, and to Roma in particular. Is the (possible) love Cleo feels for the family to be read as (emotional) false consciousness? As a symptom of the special depredation of domestic service? Or could it be read as a heroic refusal of capitalism’s commercial values? There seems to be a stark choice here. If we read Cleo (and all the characters like her) as a victim of emotion that is against her best interests—as a person robbed of her personality, her identity, her self—then we deny her agency and in effect deem her “voicing” unreliable. But if Cleo’s love, despite everything, is “freely” chosen (if it is, say, the triumph of non-capitalist, human values), then she is an agent and our speaking, working class crusader against capitalism’s relentless commodification of everything.

For many, neither is a good option. Instead, it is more comforting to ignore the prospect that the domestic might love back. It is more reassuring to imagine the domestic in melodramatic terms—as more like the Papin sisters lying in wait for an opportunity to murder their evil mistress or as a nascent revolutionary, as “Papas Fritas” does and as Richard Brody and others would like to. Focusing on the true love of the domestic brings one to the fraught terrain of self-deception, self-estrangement, and the limits of self-representation or “voicing.”

Roma, with its sousveillant narration, refuses to give form, shape, or even outline to Cleo's inner life. It raises the question of Cleo’s love. In doing that, it does what other films in the domestic service cycle also do: it raises the problem of subaltern agency and casts doubt on the project of “giving voice” as a political cure all. This does not mean that Roma arrives at an inherently conservative project. It does mean, however, that the familiar terms of political analysis, at least when they are grounded in the emotional labor of domestic service, can no longer be relied on to guide our account.

Salomé Aguilera Skvirsky works on transnational political cinema, with a special focus on Latin America. She takes a comparativist and broadly hemispheric approach to the representation of race, labor, and “the people” in moving image media. Her first book, The Process Genre: Cinema and the Aesthetic of Labor (Duke University Press, 2020), won the 2021 Best First Book Prize from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. It was a Finalist in the “Media and Cultural Studies” category for the 2021 PROSE Book Awards presented by the Association of American Publishers, and it was shortlisted for 2021 Kraszna-Krausz Moving Image Book Award. She is currently pursuing a book-length project, “Filming the Police,” which is a comparativist treatment of the topic of police on screens that brings together the ubiquity of police shows in televisual media with the surveillant and sousveillant recordings of police violence in the digital age. She is a co-editor at Critical Inquiry.

Notes:

-

1 Richard Brody, “Review: There’s a Voice Missing in Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Roma,’” The New Yorker, December 18, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-front-row/theres-a-voice-missing-in-alfonso-cuarons-roma. BACK

-

5 Bill Nichols, “The Voice of Documentary,” Film Quarterly 36, no. 3 (1983): 18. Although Nichols is explicitly focused here on documentary, I think it applies well to fiction narrative. For more on voice and filmic point of view, see Edward Branigan, Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film (Berlin: Mouton, 1984) and George M. Wilson, Narration in Light: Studies in Cinematic Point of View (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986). For more on point of view, particularly in relation to camera movement, see Daniel Morgan, “Where Are We?: Camera Movements and the Problem of Point of View,” New Review of Film and Television Studies 14, no. 2 (2016): 222–48. BACK

-

6 Caleb Crain,“‘Roma’: Through Cuarón’s Intimate Lens,” The New York Review of Books (blog), January 12, 2019, https://www.nybooks.com/daily/.... BACK

-

7 See also Diana Cuéllar Ledesma, “Rome Leads to All Roads: Power, Affection and Modernity in Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Roma,’” Third Text: Cirtical Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Culture, March 26, 2019, http://thirdtext.org/cuellar-r.... Carla Marcantonio writes, “the spoken word is not cinema’s most powerful tool.” See Carla Marcantonio, “Roma: Silence, Language, and the Ambiguous Power of Affect,” Film Quarterly 72, no. 4 (2019): 38–45. See also Elizabeth Osborne and Sofía Ruiz-Alfaro, "Introduction," in Domestic Labor in Twenty-First Century Latin American Cinema, eds. Elizabeth Osborne and Sofía Ruiz-Alfaro (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 1-22. BACK

-

8 Michael Wood, “At the Movies,” London Review of Books, January 24, 2019. BACK

-

9 Dolores Tierney, Introduction. “Special Dossier on Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma: Class Trouble.” Mediático, December 24, 2018. http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/mediatico/2018/12/24/special-dossier-on-alfonso-cuarons-roma-class-trouble/. BACK

-

10 There are exceptions. See, for example, Ignacio Sánchez Prado, “Special Dossier on Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma: Class Trouble,” Mediático, December 24, 2018, http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/mediatico/2018/12/24/special-dossier-on-alfonso-cuarons-roma-class-trouble/. Sánchez Prado acknowledges that Cleo is largely without voice in the film. BACK

-

11 Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Garden City, NY: Anchor, 1959), 151. BACK

-