Assessing Research and Progress in a Hispanic Literary and Cultural Studies Conference

Over thirty years ago, in a survey of the field similar to the one we dedicate this issue of FORMA—a call for Latin Americanists to assess the future of their discipline—several critics emphasized the importance of revisiting and diversifying the canon that shaped their research. 1 Julio Rodríguez-Luis, for example, urged researchers to shift their focus beyond the prominent writers of the 1960s and 1970s because it was becoming difficult to feel “enthusiastic about yet another article on [José Lezama Lima’s] Paradiso or on [Carlos Fuentes’s] Terra Nostra” (86). Other critics, like Sara Castro-Klarén, optimistically pointed out that “the emergence of new subjects, hitherto considered outside the gates of Ángel Rama’s ciudad letrada, is the most significant event in our literature in the last quarter century,” specifying that “the most notable subject to emerge in the last twenty-five years is the woman who writes” (28-29). Influenced by the ongoing “canon wars” in English departments in the United States at the time, expanding the canon of authors deemed valuable for study—by including those who had previously been excluded or ignored, or whose works challenged traditional conceptions of Latin American literature—and achieving greater gender equality became two of the most important topics among Latin Americanists in U.S. academia. My intention in this paper is to use data to examine the field of Spanish American studies (and Hispanic studies in general), taking the hopes and expectations expressed in the early nineties as a point of departure, and to explore whether they have been fulfilled while also identifying which authors are receiving scholarly attention in the twenty-first century.

The data for this paper comes from the Kentucky Foreign Language Conference, which has been held annually and uninterruptedly (except for 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic) at the University of Kentucky (Lexington) since 1948. Academic conferences, as a field of study, have been little theorized, and in the specific case of a literature and culture conference, as we will see, it offers a unique opportunity to focus on the subject of study in a way that is not possible in many other disciplines. As most research in this area centers on scientific conferences, I will start by highlighting two prevailing tendencies in these studies that have prompted me to adopt a different approach in examining literary and cultural conferences.

The first tendency is an emphasis on “topics.” Research on scientific conferences often concentrates heavily on how the trending topics discussed at these events reflect the evolving directions within their respective fields. This is, of course, valuable input not only for researchers seeking visibility through publications, but also for funding agencies and academic departments. It has become common practice to use various text mining techniques (such as topic modeling 2) to identify the trends dominating scientific investigation in conferences and periodicals. Studying trends involves observing which topics are gaining or losing popularity, identifying the internal or external factors responsible for these changes, and assessing whether this popularity influences publications or even the creation of new academic meetings. Explanations for why a topic disappears can be simple (e.g., a “lack of interest”or the research being superseded) or complex (e.g., sub-specializations fragmenting the topic into multiple subfields or the emergence of new areas building on it). For example, in their study of Computer and Information Science conferences, Su Yeon Kim, Sung Jeon Song, and Min Song use text mining to analyze state-of-the-art techniques and trends. 3 They track one of their topics, topic 12, related to “data mining,” over time. While they observe “no decrease in the number of papers and the number of conferences,” the topic appears to be declining because, since the late 2000s, it has begun branching out into broad application areas such as graph theory, social network analysis, and biomedical analysis (149). In contrast, studying topics presented at literature and culture conferences presents a unique challenge, as these papers typically not only have a main topic but also aim to analyze at least one text or cultural product. These cultural products come with their own titles and authors (known or anonymous), who are to some extent held responsible for the content and are situated within specific historical periods, national contexts, artistic genres, and styles. Additionally, they may belong to one or more academic fields of study. Authors of cultural products are not only part of the topic being studied; they are usually considered the main focus of these papers. Unlike topics in scientific conferences, authors do not lose importance simply because their cultural relevance has diminished—they are not “superseded”—or because approaches to their work fragment into subfields. Instead, continued relevance can result from the introduction of new topics (such as new literary or social theories) or extra-literary circumstances. Conversely, their disappearance as an object of scholarly interest can become a subject of analysis in its own right.

The other major tendency in research on academic conferences is the study gender equity. In most fields of science and technology, women continue to be underrepresented at academic conferences, which impacts the successful development of their careers. 4 Many studies on this gender gap have demonstrated a correlation between visibility at conferences and lower representation of women as invited speakers as well as the number of women on organizing committees. 5 Even in academic events where women’s participation has increased, other forms of the gender gap persist. For example, women tend to present more posters than give talks, with the latter being considered more prestigious. Additionally, when women do present, their percentage as first authors is lower. 6 Literary and cultural conferences, in contrast, tend to have a higher representation of women. While elements such as posters and multi-authored works are uncommon at these events, one aspect of research presentations can reveal gender imbalance beyond the gender of the participating scholars. From the perspective of literary and cultural conferences, what matters is not only the gender of the presenters but also the gender of the authors of the cultural products being studied and the relationship between them. In my analysis, I will focus primarily on the level of attention given to female writers and the percentage of male scholars presenting research on them. This approach also enables the examination of other aspects related to the canon in Hispanic studies, such as whether researchers—both male and female—focus on well-known, established female writers or introduce previously understudied authors.

Using a quantitative approach to any aspect of culture still faces opposition from members of Spanish American literary studies, perhaps due to the complex history between data acquisition and the study of Spanish American culture, or simply because this method of studying cultural history is still associated with the so-called “distant reading” in the minds of scholars unfamiliar with the breadth and variety of Digital Humanities (DH) approaches. Quantitative approaches to the literary field are not new within Spanish American studies and one can find early versions of them in well-known essays such as Ángel Rama’s “El boom en perspectiva. 7" The growing use of data collection and analysis by activists in contemporary Spanish American societies—employed to counter misinformation disseminated by state bodies and to promote citizen mobilization in urban life, politics, and environmental issues—will hopefully encourage more Latin Americanists in U.S. academia to embrace DH techniques for studying history and power relations in the cultural field in ways that are not traditionally possible.

Data and its Limitations

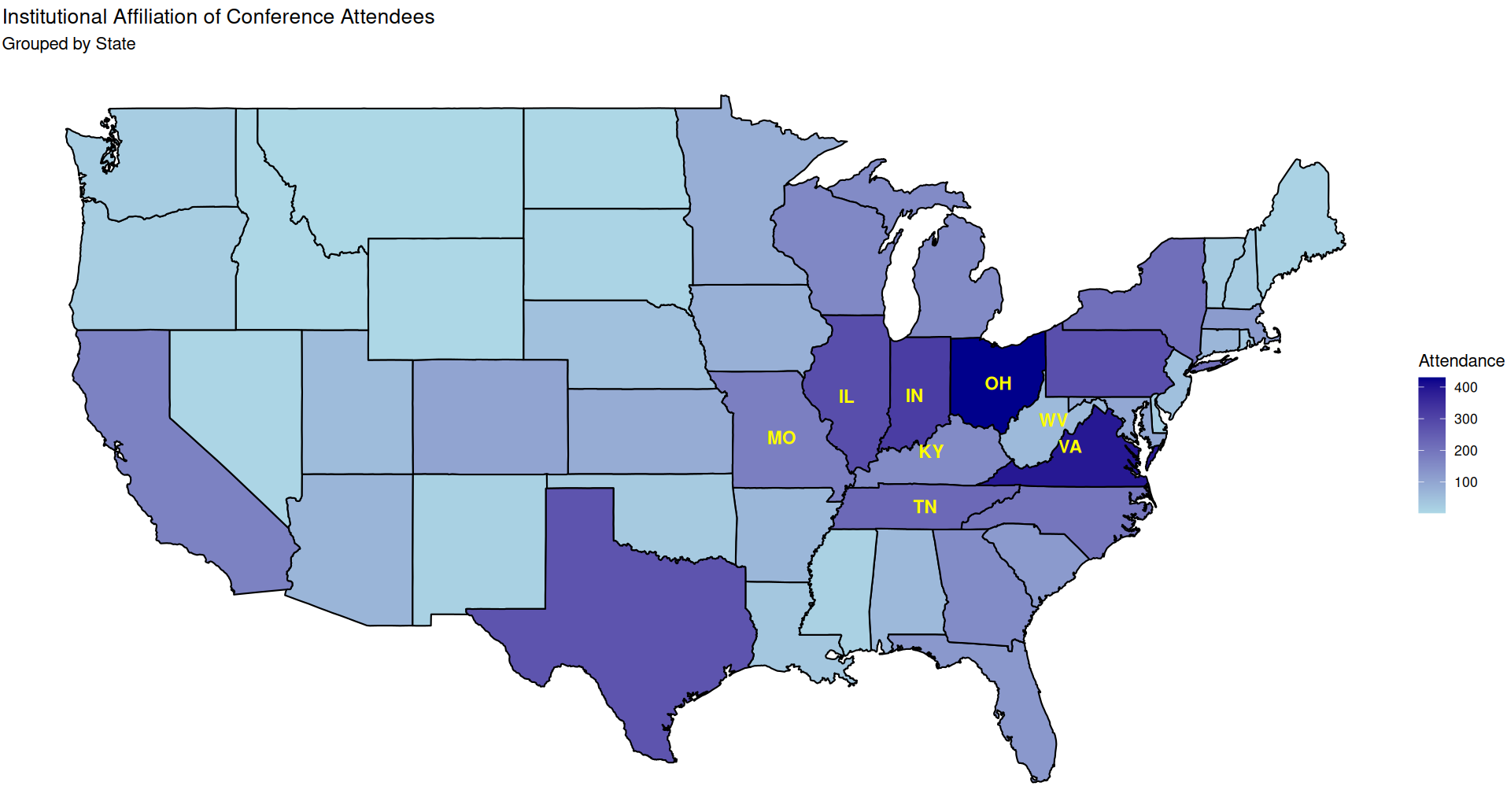

The KFLC is a national conference, as demonstrated by the diverse institutional origins of its participants. During the period under study, scholars from over 900 universities across all U.S. states and the District of Columbia (except Hawaii) attended, along with a small number of participants from countries such as Spain, Mexico, the UK, Peru, Chile, and Argentina. While, as expected, most attendees came from geographically closer institutions, particularly in the Southeast and Midwest, there was still significant representation from other regions of the country (see Figure 1). Although the conference was established in 1948, my analysis focuses on papers presented from 2000 to 2018. The number of attendees varies greatly during this period (mean = 291, SD = 40), with the highest numbers—over 300 papers—occurring between 2009 and 2015. The first phase of preparing this dataset was made possible through the collaboration of graduate assistants from the University of Nebraska (Laura GarcíaGarcía, Ana María Tudela Martínez, Olatz Sanchez-Txabarri, and Josefa Samper Suárez), who transcribed the KFLC programs in 2023. The second phase involved enriching the information found in the official documents. Data enhancement included adding details about the texts and authors analyzed in over 5,000 presentations related to Hispanic studies. My primary focus is on the research papers presented at the conference, excluding sessions on linguistics, Brazilian or Portuguese literature and culture, round tables, film or theater exhibitions, and poetry readings. 8 KFLC sessions cover both Peninsular and Latin American literature and culture. While my work primarily focuses on the latter, it will be necessary to reference and compare it with the Peninsular literature and culture presentations, with which Latin American literature coexists within North American academia.

Figure 1. Conference site for KFLC (KY) and bordering states.

As mentioned above, data was obtained from the official conference programs and did not include access to abstracts or the actual papers presented. This made the task of identifying the authors studied in each presentation more challenging. Data enhancement benefited, however, from the field’s tradition of including the author’s name—and often the work(s) studied—in presentation titles. This approach made it possible to identify the primary author(s) analyzed in approximately 70% of cases, with yearly figures ranging from 65% to 75%. Unfortunately, this also means that even if one can identify the main author studied, it is impossible to say with absolute certainty that all authors studied in each presentation have been accounted for. For the parts of my essay that study the gender of conference attendees I use the entire dataset of 5,427 observations. The data gets reduced to 3,814 when I exclude papers in which the main author(s) of the cultural product(s) have not been identified. This is the information I use for exploring gender parity, canonicity and scholarly attention. 9 Throughout this essay, I will use the term “author” to refer to the creator of a cultural product (e.g., writers of literature, film and TV directors, artists) and “work” to refer to any cultural object (e.g., literary texts, film, graphic novels) produced by an author. To avoid confusion, when referring to the author of the paper presented at the conference, I will use the expression “research author” or simply “researcher.” For variety, I use the word “mentions” to refer to frequency, that is, how often an author has been the subject (or one of the subjects) of a paper in the conference.

Gender Representation, Thirty Years Later

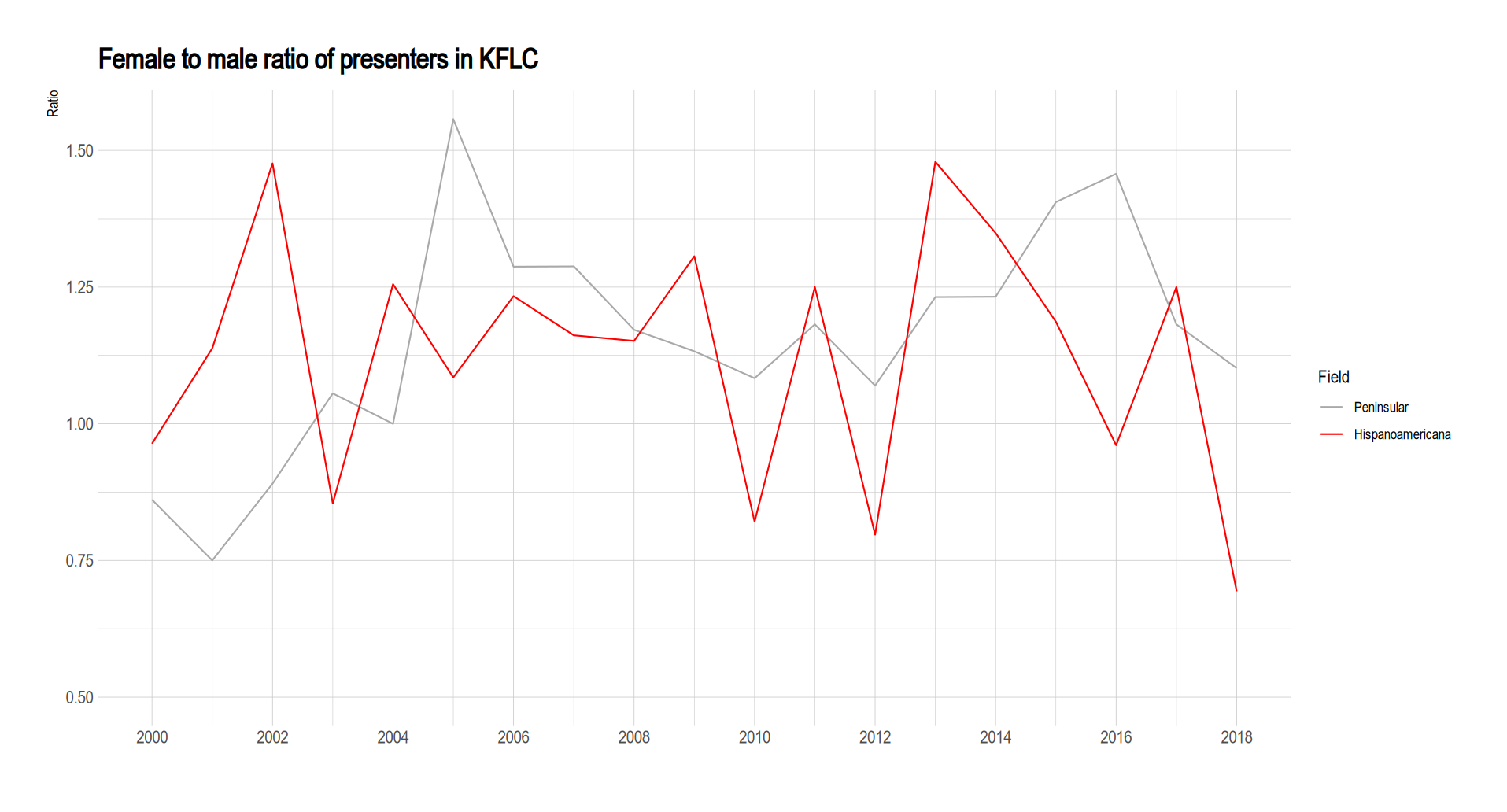

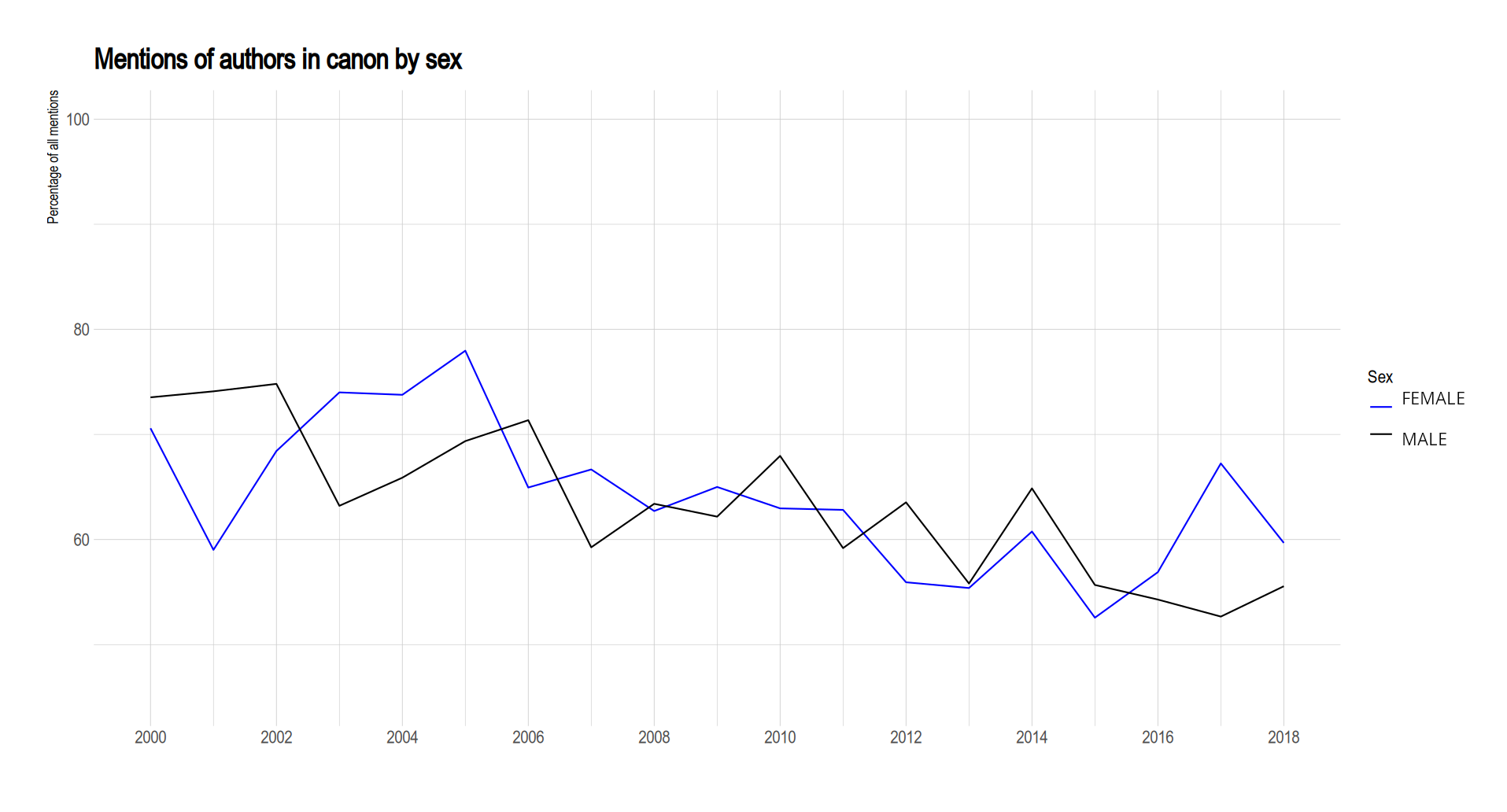

Any examination of how conference meetings have changed in the twenty-first century should begin with gender parity. Unlike many scientific academic conferences, the KFLC consistently shows a strong balance between male and female scholars, often favoring women. Since 2000, this gender ratio peaked in 2013 at 1.34 in 2005 and 1.33 in 2015 and reached its lowest in this century in 2018 (0.89). As shown in Figure 2, when examining each field individually, the ratio has favored women in Peninsular literature since 2003. In contrast, the Spanish American field has experienced fluctuations which are responsible for the overall decline observed in 2018. While these numbers suggest that gender parity in participation has been achieved, it is essential to reflect on what this balance means for another kind of equality: the scholarly interest in “the woman who writes,” one of the “new subjects” referenced by Castro-Klarén in her 1992 essay. In sharp contrast to the gender balance among scholars participating in the field, the authors on whom these papers focus remain overwhelmingly male. 29% of the papers presented at the KFLC have centered on women writers as the primary subject—a figure that has changed little over nearly 20 years. The highest point was in 2007, with 35%, and the lowest in 2009 and 2010, with 23%. However, the most striking aspect of these figures is the low number of male scholars presenting papers on women writers.

Figure 2. Female to male researcher ratio.

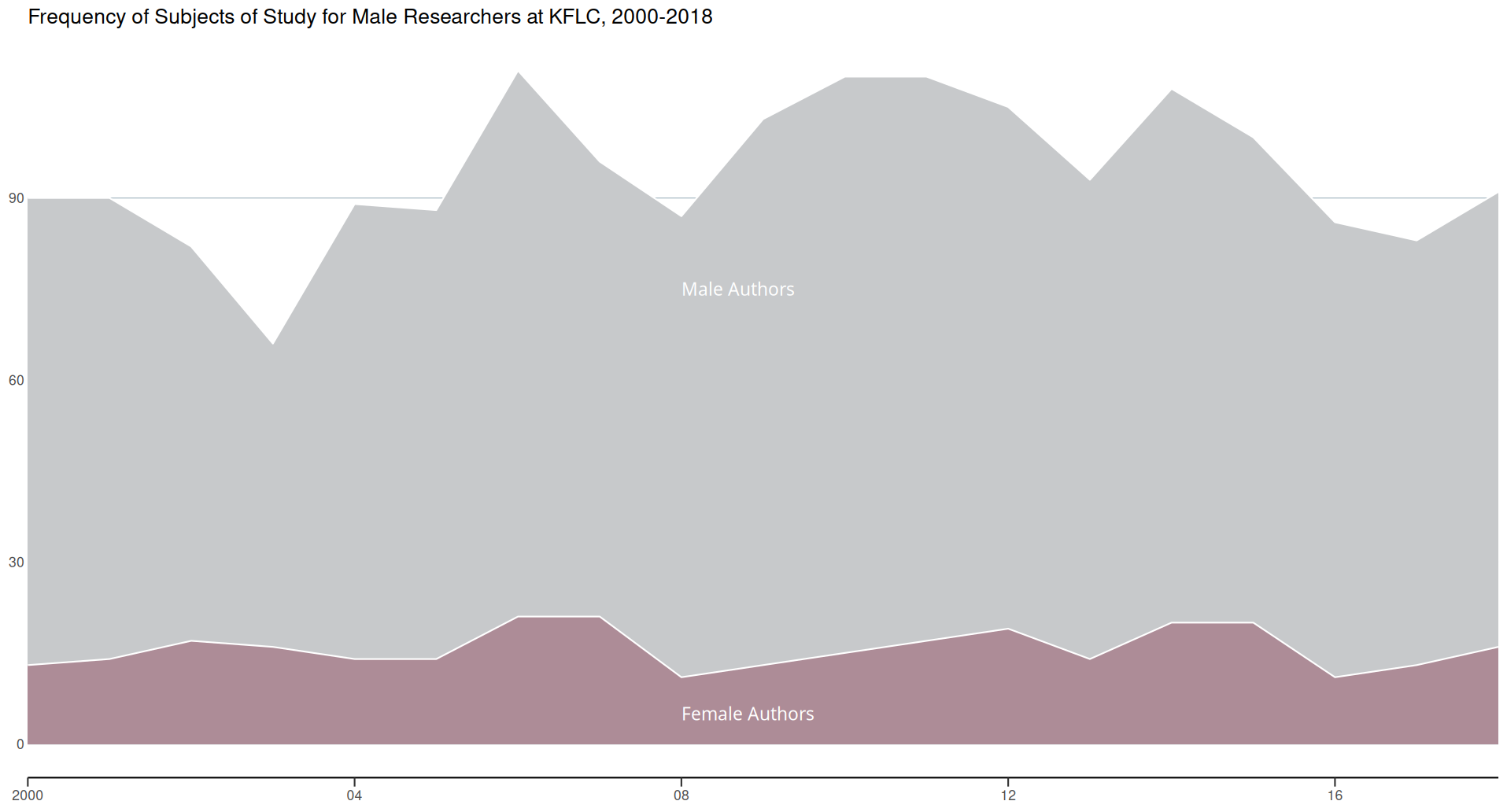

When examining the papers presented by male scholars, either working alone or in collaboration with others, only 17% of their studies focused on women authors. Figure 3 visualizes the contrast between the number of papers by male scholars analyzing male authors (range 51- 98) and female authors (11 to 21) per year. And although most women authors are studied by female researchers, over 70% of female scholars at the conference focus on cultural products created by men. When broken down by field, as Figure 4 shows, Spanish American literature male scholars perform slightly better than their Peninsular counterparts, with percentages reaching the thirties a few times, but the overall number of researchers working on female authors remains a modest 20%.

Figure 3. Subjects of study for male researchers.

Figure 4. Yearly percent of papers by field.

It can be argued that the percentage of papers on female authors at the KFLC (29%) shows a slight improvement in terms of scholarly attention to this group when contrasted to other indicators of influence in the field. For example, Joan L. Brown’s research shows that during the 1990s, the presence of women on graduate reading lists was only 13% (676 male, 102 female) ranging from “highs of 16% for Spanish literature and 35% for Spanish American literature, to lows of zero for Spain and 2% for Latin America. 10" Recent versions of this graduate school requirement also show that the percent of female authors included is only 18%, though contemporary reading lists, in those universities that continue to use them, appear to be more diverse in their composition. 11 Thus, while the research presented at the KFLC shows an increase in attention to women authors, this progress falls far short of parity and has been driven primarily by the efforts of female scholars in the field.

There are other aspects of this data that raise important questions about the optimism regarding the increased focus on women writers, particularly in relation to the influence of canonical works on research. There are 1,236 mentions of 459 women authors as subjects of study in 1,117 research papers, sometimes centering on a single author, and other times comparing multiple authors (including both female and male authors), but the frequency of focus on these female authors is uneven. The top 10% (47 authors) account for 48% of those mentions. This reflects not a gender disparity, but a pattern of canonization. A similar trend appears with male authors, where the top 10% (120 of 1,197 male authors) account for half of the instances of focus. What is particularly striking is that over 64% of both male and female authors received only one mention, that is, they are subjects of only a single paper. Among women, 63% (290 of 459) were studied just once, with no further attention. The same holds for men, where 64% (777 of 1,197) were studied only once in nineteen years of data. While a diverse range of voices is being studied, most receive only fleeting attention from scholars. If one momentarily proposes the hypothesis that this type of unbalanced distribution between frequently studied authors and the rest of the field is typical of any literature conference (a different type of study with more data would be needed to test this hypothesis, of course), then it becomes clear that the issue in advancing diversity is not the lack of balance—the fact that some writers receive a disproportionate amount of attention—but rather who is receiving that attention. The fact that the dominant voices at the top shift only infrequently over time is undoubtedly an indication that certain fields of study are closely tied to the interests and careers of academics. So, who is at the top? How many of the authors with staying power are non-canonical?

Dominance of the Canon

Examining the authors with the highest frequencies offers only a limited glimpse into what is being studied, providing little insight into how many new authors are being introduced as subjects of study. A more accurate understanding of who is included or excluded, and which authors remain dominant over time at a conference, can be achieved by comparing the studied authors to those in the literary canon. Since this study focuses on a cultural and literary conference held in the United States, the most logical approach is to reference a canon produced by scholars who are part of American academia. To establish this canon, I use a dataset listing the most frequently included authors on the previously mentioned reading lists for doctoral and master’s programs in U.S. graduate schools. 12 While no list of the current canon can be entirely comprehensive, this approach ensures that it reasonably reflects what is taught or required in over 90 U.S. academic institutions offering graduate programs in Spanish. Though this method is not a flawless way to determine which authors are considered canonical, it can be argued that an author’s inclusion on these lists suggests they have been deemed canonical by an academic with expertise in Hispanic literature and culture at a U.S. institution, either through study or instruction. Even if some authors were included in graduate reading lists with the intent of disrupting the canon, comparing these lists with the authors featured in KFLC conference papers would reveal how many presenters engage with authors outside the traditional reading lists. In other words, it would be insightful to examine the extent to which research papers introduce new voices or primarily reinforce the already established cultural capital. Additionally, this approach has the added benefit of making visible possible connections between teaching and research. 13

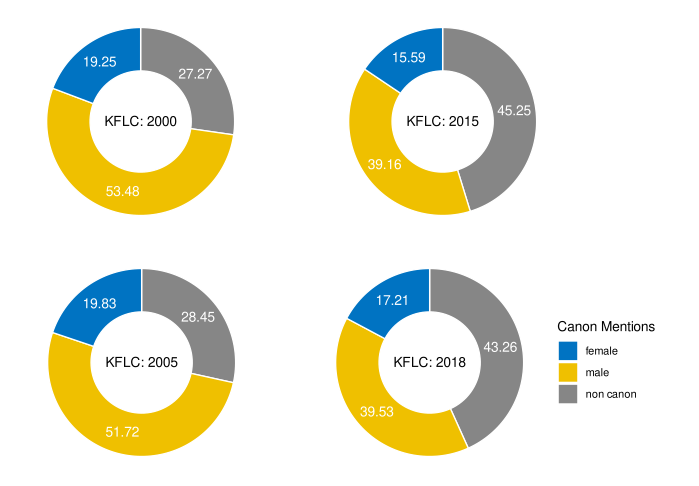

The graduate reading list canon includes 1,108 non-anonymous authors, 21% of whom are female. Comparing this list with the KFLC data reveals that slightly less than a third (515) of the 1,656 unique authors studied at KFLC are included in the canon. However, this does not mean that the conference mainly focuses on non-canonical authors; on the contrary, the majority of papers presented each year concentrate on authors from that one-third who are part of the canon. Sixty-three-and-a-half percent of mentionsin conference papers are from canonical authors, with 64.2 percent for female authors and 63.2 percent for male authors. As Figures 5 and 6 illustrate, canonical dominance was more pronounced in the early part of the century but still accounts for over 50% of the authors scholars focus on in 2018.

Figure 5. Canonical authors presence per year.

Figure 6. Canonical authors and non-canonical authors presence per year.

The shift between canonical dominance in 2000 and 2005, compared to the later years of the decade, reflects an increase in mentions of non-canonical authors. The “gray area” in Figure 6 continues to expand as more non-canonical authors are studied, suggesting that the conference serves both as a space for exploring new voices and as an opportunity for scholars to pursue fresh research topics. However, this gray area also includes a significant number of authors with very low overall frequencies or those who disappear from study after a single appearance. From that group, approximately 85% come from outside the reading list canon. In other words, most non-canonical authors belong to this ephemeral group, whose brief presence in research papers is not enough to leave a lasting impact or challenge the canon permanently. This trend may reflect a post-canon wars era, where non-canonical authors are briefly introduced but, with few exceptions, tend to fade away after one or two dedicated papers, receiving limited attention.

Conclusions and Future Work

My essay began by citing the observations and hopes expressed thirty years ago by two Latin American studies scholars regarding the future of research in the field. While we currently lack precise data on the state of research at the time Castro-Klarén optimistically predicted growing academic interest in female authors, the available KFLC data suggests that the study of Spanish-language literature in the United States still primarily focuses on male authors. From this view, achieving gender parity remains a distant goal. At the same time, it is difficult to determine whether the wish expressed by Rodríguez-Luis for scholars to write about non-canonical authors has been fulfilled. For instance, interest in many authors who were popular among Latin Americanists in the early 1990s has certainly waned, but a canon still exists, affecting both male and female authors. A small group of authors become the focus of papers, while those outside that canon only occasionally receive attention. José Lezama Lima or Carlos Fuentes might not receive as much attention as they once did, but other authors have replaced them as canonical figures capturing most of the attention.

Future analysis of conference data will aim to gain insights into trends from the decades preceding the twenty-first century. Including additional conferences beyond KFLC is likely not feasible at this time, as it would demand more time and resources for data collection and preparation than I have currently available. However, I believe that the greatest challenge in analyzing conferences lies not in collecting new data but in learning how to handle low-frequency occurrences—particularly the many authors who appear only once in the dataset—and determining how to assess these instances to better understand which authors are currently receiving attention and which have diminished as subjects of interest. Tracking individual authors based solely on frequency data may not be ideal, as academic attention cannot always be measured by an author’s absence from conference topics. Some authors with high overall mention counts experience gaps of several years—sometimes two or three—during which no papers are presented about them, only to reemerge later with even higher counts. This reappearance could result from various factors, such as the publication of new works or non-literary reasons. Similarly, finding a method to determine how long after an author’s last mention they can be considered no longer a focal point for researchers and indicating a decline in scholarly attention, will be crucial for future work.

José Eduardo González is Associate Professor of Spanish and Ethnic Studies at University of Nebraska-Lincoln. His area of specialization is recent and contemporary Latin American Narrative with a focus on Digital Humanities methodologies. He is the author of Appropriating Theory: Ángel Rama's Critical Work (2017) and Borges and the Politics of Form (1998). He is editor or co-editor of multiple volumes of Latin American criticism and theory, including Approaches to Teaching the Works of Jorge Luis Borges (2025) and Ángel Rama's Spanish American Literature in the Age of Machines and Other Essays (2024).

Notes:

-

1 I am referring to a special issue (Vol. 20, No. 40) published by the Latin American Literary Review in 1992 to mark its 20th anniversary, with an introduction by Carlos J. Alonso. In addition to Sara Castro-Klarén and Julio Rodríguez-Luis, whose essays I mention in my article, several other critics were invited to contribute. Among them, to name only a few, are Antonio Benítez-Rojo, John Beverley, John S. Brushwood, Raquel Chang-Rodríguez, David William Foster, Jean Franco, and Roberto González Echevarría. See Sara Castro-Klarén, “Situations,” Latin American Literary Review 20.40 (1992): pp. 26-29; and Julio Rodríguez-Luis, “On the Criticism of Latin American Literature,” Latin American Literary Review 20.40 (1992): pp. 85-87. BACK

-

2 Topic modeling is a technique derived from NLP (natural language processing) studies that is used to group similar words that are connected to each other based on a semantic pattern. These groups of words are called “topics” and each topic is a representation of a concept being discussed in some part of the text. BACK

-

3 See Su Yeon Kim, Sung Jeon Song, and Min Song, “Investigation of topic trends in computer and information science by text mining techniques: From the perspective of conferences in DBLP,” Journal of the Korean Society for Information Management 32.1 (2015): pp. 135-152. BACK

-

4 See Carmen Corona-Sobrino, Mónica García-Melón, Rocio Poveda-Bautista, Hannia González-Urango, “Closing the Gender Gap at Academic Conferences: A Tool for Monitoring and Assessing Academic Events,” PLoS One 15.12 (2020): e0243549, https://doi.org/10.1371/journa.... BACK

-

5 Florence Débarre, Nicolas O. Rode, and Line V. Ugelvig, “Gender Equity at Scientific Events.” Evolution Letters 2.3 (2018): p. 152. BACK

-

6 See Lynne A. Isbell, Truman P. Young, and Alexander H. Harcourt, “Stag Parties Linger: Continued GenderBias in a Female-Rich Scientific Discipline,” PloS One 7.11 (2012): e49682, https://doi.org/10.1371/journa.... BACK

-

7 Ángel Rama, “El boom en perspectiva,” La Novela en América Latina. Panoramas 1920–1980 (Montevideo: Fundación Ángel Rama, 1986), pp. 235–293. BACK

-

8 Given the slow process of enriching the data, excluding Portuguese and Brazilian studies was an early decision, but future studies will hopefully incorporate that information. In addition to the aforementioned graduate assistants, I would like to thank Kelly Ferguson for establishing the initial contact with the KFLC organizing committee and Daniel Batten for scanning the KFLC programs that were not available in digital form. This project also benefited from a “Spark” research grant from the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Nebraska in 2023. BACK

-

9 The mean for papers whose main subject of study has been identified is 205, SD=30. Some of the papers include anonymous authors in combination with a non-anonymous author. As long as there is at least one author whose gender is identified, the paper is included. Later, for the study of author frequencies in relation to gender and the canon, I also exclude all anonymous authors. BACK

-

10 Joan L.Brown, Confronting Our Canons: Spanish and Latin American Studies in the 21st Century (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2010), p. 105. BACK

-

11 José Eduardo González, Elliott Jacobson, Laura García García, Leonardo Brandolini Kujman, “Measuring Canonicity: Graduate Reading Lists in Departments of Hispanic Studies,” Journal of Cultural Analytics 6.1 (2021): pp. 6, 18, https://doi.org/10.22148/001c..... BACK

-

12 The information about graduate reading lists used to establish the “canon” for studying the KFLC data comes from González, et. al., “Measuring Canonicity.” BACK

-

13 One of the main limitations of this method for evaluating the presence of canonical authors is that the data for graduate reading lists was collected between 2019 and 2020, while the KFLC conference information spans back to 2000. This time gap makes it impossible to determine, year by year, whether the authors discussed at the conference were considered part of the canon at the time or if they were added or removed later. As a result, my analysis is necessarily shaped by a contemporary perspective—regardless of whether a paper on an author was presented five or twenty years ago, my primary goal in this part of the essay is to determine which authors are now recognized as part of the canon. BACK